1. Introduction to Sample Size Determination

2. The Importance of Sample Size in Experimental Research

3. Understanding the Connection

4. Key Factors Influencing Sample Size Calculation

5. Common Methods for Determining Optimal Sample Size

6. Sample Size Considerations for Different Study Designs

7. Adjusting Sample Size for Population Variability

8. Software and Tools for Sample Size Estimation

9. Best Practices and Ethical Considerations in Sample Sizing

Sample Size Determination: Optimizing Sample Size: A Critical Factor for Accurate Experimental Data

1. Introduction to Sample Size Determination

determining the appropriate sample size is a pivotal step in experimental design that directly impacts the validity and reliability of research findings. A sample size that is too small may fail to detect a true effect, while an overly large sample can waste resources and potentially expose more subjects than necessary to any risk. The process of sample size determination is influenced by various factors, including the expected effect size, the level of precision desired, the population size, and the statistical power required to confidently detect an effect.

From a statistician's perspective, the primary concern is ensuring that the sample size is large enough to provide a high probability (power) of detecting a true effect if it exists. This involves calculations that consider the acceptable levels of Type I and Type II errors. A Type I error occurs when a true null hypothesis is incorrectly rejected, while a Type II error happens when a false null hypothesis is not rejected. Balancing these risks is essential for robust statistical analysis.

From a practical standpoint, researchers must also consider logistical constraints such as time, budget, and available subjects. In some cases, the ideal sample size suggested by statistical calculations may not be feasible, and researchers must make adjustments accordingly, often requiring a compromise between statistical ideals and practical limitations.

Here are some key points to consider when determining sample size:

1. Effect Size: The smaller the effect size you wish to detect, the larger the sample size you will need. For example, if a medication is expected to lower blood pressure by a small margin, a larger group of patients would be required to confirm this effect compared to a medication expected to have a more significant impact.

2. Confidence Level and Margin of Error: The confidence level indicates how sure you can be that the results reflect what you would expect to see in the entire population. The margin of error reflects the range within which the true population parameter lies. For instance, a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error is common in many studies.

3. Population Variability: More variable populations require larger sample sizes. If you're studying a trait with high variability, such as human height, you'll need a larger sample than if you were studying a trait with low variability, like the number of seeds in an apple.

4. Population Size: For smaller populations, the sample size doesn't need to increase linearly with the population size. Once the population exceeds a certain threshold, the required sample size grows very slowly. This is known as the finite population correction.

5. Desired Statistical Power: Typically, a power of 80% or 90% is sought. This means that there's an 80-90% chance of detecting an effect if there is one. To achieve higher power, a larger sample size is needed.

6. Sampling Method: The method of sampling, whether it be random, stratified, or cluster sampling, will also affect the sample size. Random sampling is generally the most straightforward approach, but stratified sampling can be more efficient if there are known subgroups within the population.

To illustrate these concepts, let's consider an example. Suppose a researcher wants to estimate the average height of adult males in a city with a population of 100,000. If previous studies suggest that the standard deviation of male heights is around 3 inches, and the researcher desires a 95% confidence level with a margin of error of 0.5 inches, the required sample size can be calculated using the formula for the sample size of a mean:

$$ n = \left(\frac{Z_{\alpha/2} \cdot \sigma}{E}\right)^2 $$

Where:

- \( n \) is the sample size,

- \( Z_{\alpha/2} \) is the Z-score corresponding to the desired confidence level (1.96 for 95% confidence),

- \( \sigma \) is the population standard deviation,

- \( E \) is the margin of error.

Plugging in the values, we get:

$$ n = \left(\frac{1.96 \cdot 3}{0.5}\right)^2 \approx 138.29 $$

Rounding up, the researcher would need a sample size of at least 139 adult males to estimate the average height with the desired level of precision.

Sample size determination is a multifaceted process that requires careful consideration of statistical principles and practical constraints. By understanding and applying these principles, researchers can optimize their sample size to achieve accurate and reliable experimental data.

Introduction to Sample Size Determination - Sample Size Determination: Optimizing Sample Size: A Critical Factor for Accurate Experimental Data

2. The Importance of Sample Size in Experimental Research

The cornerstone of any experimental research is the reliability and validity of the data collected, which hinges significantly on the sample size. A sample size that is too small may lead to results that are not representative of the population, while an excessively large sample can be wasteful of resources and may even complicate the analysis with too much data. The key is to find a balance that optimizes the accuracy and precision of the experimental outcomes.

From a statistician's perspective, the sample size is critical for ensuring the power of a study. The power is the probability that the study will detect an effect when there is one to be detected. A larger sample size can increase the power of a study, thereby reducing the risk of a Type II error, which occurs when a study fails to detect an effect that is present.

From the researcher's point of view, determining the right sample size is essential for the credibility of the experiment. It is a common pitfall for researchers to embark on a study with a preconceived notion of the required sample size without conducting a proper power analysis. This can lead to inconclusive or misleading results that fail to contribute meaningfully to the body of knowledge.

Here are some in-depth points to consider regarding sample size in experimental research:

1. Statistical Significance: The larger the sample size, the more likely it is that the study will detect a statistically significant difference if one exists. This is because the standard error, which is inversely related to the square root of the sample size, decreases as the sample size increases.

2. Effect Size: The sample size is also dependent on the expected effect size. Smaller effect sizes require larger samples to be detected, whereas larger effects can be identified with smaller samples.

3. Population Variability: If the population is heterogeneous, a larger sample will be necessary to capture the range of variability within the population. This ensures that the sample is truly representative.

4. cost-Benefit analysis: Researchers must also consider the cost implications of their sample size. Larger samples mean more resources in terms of time, money, and manpower. A balance must be struck between the ideal sample size for statistical purposes and what is practical for the study.

5. Ethical Considerations: In some fields, particularly in clinical trials, the sample size has ethical implications. Enrolling too many participants can expose more individuals to potential risks without added benefit, while too few participants can lead to inconclusive results that necessitate further testing.

Example: Consider a clinical trial testing a new drug. If the expected effect size is small, the trial will need a large number of participants to ensure that any effect of the drug is not due to chance. However, if the drug is expected to have a large effect, the trial can achieve the same level of confidence with fewer participants.

The determination of sample size is a multifaceted decision that requires careful consideration of statistical, practical, and ethical factors. It is not merely a number to be calculated but a critical component that can dictate the success or failure of a study. By optimizing sample size, researchers can ensure that their findings are both robust and reliable, contributing valuable insights to their respective fields.

The Importance of Sample Size in Experimental Research - Sample Size Determination: Optimizing Sample Size: A Critical Factor for Accurate Experimental Data

3. Understanding the Connection

In the realm of statistical analysis, the concepts of statistical power and sample size are inextricably linked, forming the backbone of any experimental design. Statistical power, the probability that a test will correctly reject a false null hypothesis, is a critical factor in determining the reliability of an experiment's results. Conversely, sample size—the number of observations or data points collected in a study—directly influences this power. A larger sample size can lead to more accurate estimates of population parameters, reducing the margin of error and increasing the likelihood of detecting true effects. However, it's not just about having more data; it's about having the right amount of data to confidently make inferences without wasting resources.

From a researcher's perspective, understanding this connection is paramount. It's a delicate balance to strike: too small a sample size may lead to a study lacking the power to detect meaningful differences or relationships, while too large a sample may be unnecessarily costly and time-consuming. Here are some key points to consider:

1. Determining Minimum Sample Size: The minimum sample size required for a study is calculated based on desired power (typically 80% or higher), the significance level (commonly set at 0.05), and the expected effect size. This calculation ensures that the study has a high probability of detecting the effect if it exists.

2. effect size: The effect size is a quantitative measure of the magnitude of the experimental effect. The larger the effect size, the smaller the sample size required to achieve the same level of power.

3. Significance Level: The significance level, denoted as alpha, is the threshold at which the null hypothesis is rejected. A lower alpha requires a larger sample size to maintain power, as it reduces the likelihood of a Type I error (false positive).

4. Variability in Data: Higher variability within the data requires a larger sample size to achieve the same level of power. This is because increased variability makes it harder to detect a true effect.

5. One-tailed vs. Two-tailed Tests: A one-tailed test, which predicts the direction of the effect, requires a smaller sample size compared to a two-tailed test, which does not predict the direction.

Example: Consider a clinical trial testing a new drug's effectiveness. If previous studies suggest a moderate effect size, a researcher might use a power analysis tool to determine that a sample size of 100 participants is needed to achieve 80% power with an alpha of 0.05. If the actual effect size is smaller than expected, the study may end up being underpowered, risking a failure to detect the drug's true impact.

In practice, researchers must weigh the theoretical calculations with practical considerations, such as the available population size and resource constraints. It's a multidimensional decision-making process that requires input from statisticians, subject matter experts, and logistical planners. Ultimately, the goal is to gather enough data to provide clear, actionable insights without overextending the study's scope. This careful planning and understanding of statistical power and sample size not only ensure ethical research practices but also contribute to the advancement of knowledge in a meaningful way.

Understanding the Connection - Sample Size Determination: Optimizing Sample Size: A Critical Factor for Accurate Experimental Data

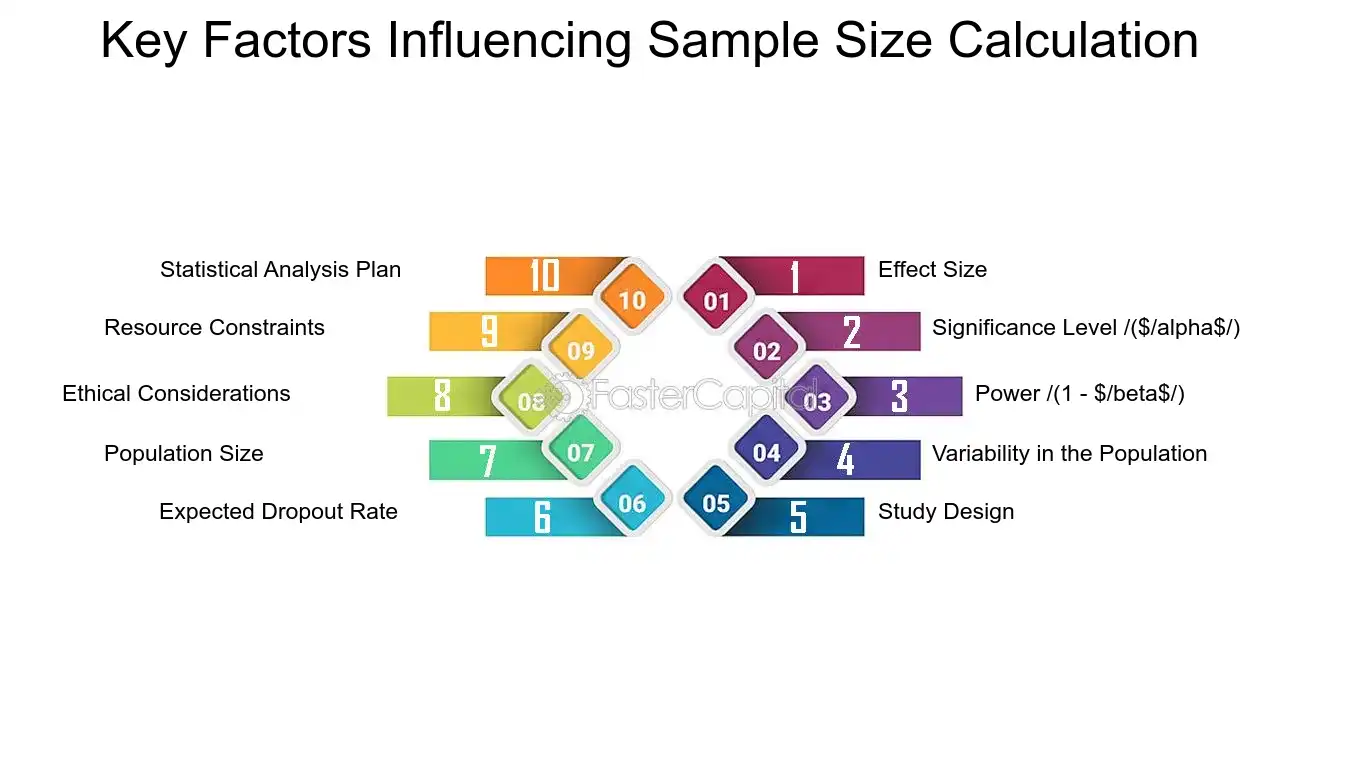

4. Key Factors Influencing Sample Size Calculation

determining the optimal sample size is a pivotal aspect of experimental design that can significantly impact the validity and reliability of research findings. A sample size that is too small may fail to detect a true effect, while an excessively large sample can waste resources and potentially expose participants to unnecessary risk. The calculation of sample size is influenced by several key factors, each playing a crucial role in ensuring that the data collected can support meaningful and statistically sound conclusions. These factors must be carefully considered and balanced to optimize the research outcomes.

1. Effect Size: The anticipated effect size is a measure of the magnitude of the phenomenon under investigation. A larger effect size requires a smaller sample to detect the same level of statistical significance. For example, if a medication is expected to reduce symptom severity by a large margin, fewer participants may be needed to observe this effect compared to a medication with a more modest impact.

2. Significance Level ($\alpha$): The significance level, often set at 0.05, represents the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is actually true (Type I error). A lower $\alpha$ reduces the risk of false positives but necessitates a larger sample size.

3. Power (1 - $\beta$): Power is the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis when it is false (detecting a true effect). Standard power levels are typically set at 0.80 or 0.90. Higher power requires a larger sample size but increases the likelihood of detecting an effect if one exists.

4. Variability in the Population: Greater variability or standard deviation within the population requires a larger sample size to achieve the same level of precision. For instance, if blood pressure readings in a population vary widely, more subjects would be needed to accurately estimate the effect of a new antihypertensive drug.

5. study design: The design of the study, whether it's cross-sectional, longitudinal, or based on repeated measures, influences sample size. Repeated measures designs can often make more efficient use of a smaller sample size because they control for between-subject variability.

6. Expected Dropout Rate: Anticipating the dropout rate is essential, especially in longitudinal studies. If a significant proportion of participants are expected to leave the study, the initial sample size should be increased accordingly to ensure enough data is available at the study's end.

7. Population Size: For studies targeting a specific population, the total population size can affect sample size calculations. In smaller populations, a larger proportion of the population may be required to obtain a representative sample.

8. ethical considerations: Ethical considerations may limit the sample size, especially in clinical trials where there is potential risk to participants. The sample size should be large enough to answer the research question but not so large as to expose an excessive number of individuals to potential harm.

9. Resource Constraints: Practical considerations such as time, budget, and available personnel can limit the feasible sample size. Researchers must balance the ideal statistical requirements with the resources they have at their disposal.

10. Statistical Analysis Plan: The choice of statistical tests and the complexity of the data analysis can influence the required sample size. More complex analyses, such as multivariate tests, may require larger samples to ensure adequate power.

By carefully considering these factors, researchers can calculate a sample size that is both statistically appropriate and practically feasible, thereby enhancing the integrity and impact of their research. It's a delicate balance between statistical demands and real-world constraints, one that requires thoughtful deliberation and expertise.

Key Factors Influencing Sample Size Calculation - Sample Size Determination: Optimizing Sample Size: A Critical Factor for Accurate Experimental Data

5. Common Methods for Determining Optimal Sample Size

Determining the optimal sample size is a pivotal aspect of experimental design that can significantly influence the validity and reliability of research findings. An adequately sized sample ensures that the study has sufficient power to detect a true effect, while also considering resource constraints and ethical considerations. Researchers must balance the need for precision and confidence in their results with the practicalities of data collection. This balance is achieved through various established methods, each with its own set of assumptions and applicability depending on the research context.

1. Power Analysis: A fundamental approach is power analysis, which calculates the minimum sample size required to detect an effect of a given size with a certain degree of confidence. Power analysis is contingent on several factors, including the effect size, significance level (alpha), and the desired power (1-beta), where beta is the probability of a Type II error. For example, a study aiming to detect a small effect size with 80% power and a 5% significance level will require a larger sample than one looking for a large effect under the same conditions.

2. Confidence Interval Width: Another method involves determining sample size based on the desired width of the confidence interval for an estimate. Narrower intervals require larger samples. For instance, if a researcher wishes to estimate the mean blood pressure of a population with a confidence interval that is ±2 mmHg wide, they will need a larger sample than if they were content with a ±10 mmHg interval.

3. Resource Constraints: Often, the sample size is dictated by the resources available, including time, budget, and personnel. In such cases, researchers must work within these limits while striving to maximize the study's validity. For example, a preliminary study might be conducted with a smaller sample due to funding restrictions, with the understanding that the results will guide future research with more extensive sampling.

4. Ethical Considerations: When dealing with sensitive populations or scarce populations, ethical considerations may limit the sample size. For example, research involving endangered species or rare diseases may only have a small pool of potential subjects, necessitating the use of specialized statistical techniques to make the most of the limited data.

5. Historical Data and Pilot Studies: utilizing historical data or conducting pilot studies can inform sample size decisions. These methods allow researchers to estimate parameters such as variance and effect size more accurately, leading to more precise sample size determinations. For instance, a pilot study might reveal that the standard deviation of a measurement is smaller than initially anticipated, allowing for a reduction in the required sample size.

6. Adaptive Designs: In some cases, researchers may employ adaptive designs that allow for modifications to the sample size based on interim results. This approach can be particularly useful in clinical trials where the effect of a treatment may become apparent before the study's conclusion.

7. Bayesian Methods: Bayesian statistics offer an alternative framework for sample size determination, where prior knowledge is combined with current data to make inferences. This method can be especially advantageous when prior information is robust and can significantly inform the analysis.

Determining the optimal sample size is a multifaceted decision-making process that integrates statistical reasoning with practical considerations. By carefully selecting the appropriate method for their specific research question, scientists can ensure that their studies are both efficient and robust, yielding reliable and actionable insights.

Don't know how to start building your product?

FasterCapital becomes your technical cofounder, handles all the technical aspects of your startup and covers 50% of the costs

6. Sample Size Considerations for Different Study Designs

Determining the appropriate sample size is a pivotal aspect of designing a study that is often underestimated in its complexity. The sample size affects the power of a study, which is the probability of detecting an effect if there is one to be detected. Too small a sample size and the study may fail to find a real effect; too large, and resources are wasted. Different study designs require different considerations for sample size. For instance, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) might need a larger sample size compared to a case-control study to achieve the same power due to the nature of randomization and control for confounding variables. Similarly, cross-sectional studies, which provide a snapshot of a population at a single point in time, might require a different approach to sample size determination than longitudinal studies, which observe the same subjects over a period of time.

Here are some key considerations for different study designs:

1. randomized Controlled trials (RCTs): The gold standard for clinical research, RCTs require careful calculation of sample size to ensure adequate power. The sample size depends on the expected effect size, the level of significance (usually set at 0.05), and the desired power (commonly 80% or 90%). For example, if a new drug is expected to reduce the incidence of a disease by 20% compared to a placebo, the sample size must be large enough to detect this difference with high probability.

2. Cohort Studies: In cohort studies, where groups of individuals are followed over time, sample size must account for attrition rates. For example, if a study is following a cohort of patients for 10 years, the initial sample size must be inflated to account for the expected number of participants who will drop out or be lost to follow-up.

3. case-Control studies: These studies are retrospective and compare individuals with a specific outcome (cases) to those without (controls). The sample size calculation must consider the ratio of cases to controls, which can affect the study's power. A common practice is to use a 1:1 ratio, but some studies may opt for a different ratio, such as 1:2 or 1:4, to increase efficiency.

4. Cross-Sectional Studies: The sample size for cross-sectional studies is often determined based on prevalence estimates. If the prevalence of the condition being studied is low, a larger sample size will be needed to ensure that enough cases are included to provide reliable estimates.

5. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: Although these studies do not collect new data, they still require consideration of sample size in terms of the number of studies included in the analysis. A meta-analysis with too few studies may lack the power to detect an effect, while one with many studies may be able to detect even small effects.

6. Qualitative Studies: Unlike quantitative studies, qualitative research does not typically involve numerical sample size calculations. However, considerations such as saturation—the point at which no new themes are emerging from the data—are important. For example, in-depth interviews may continue until saturation is reached, which could mean interviewing 20, 30, or more participants.

In practice, sample size determination is often an iterative process involving statistical calculations and practical considerations. For example, a researcher planning an RCT to test a new intervention for diabetes management might start with a power analysis to determine the minimum sample size needed. However, they must also consider the feasibility of recruiting enough participants, which might lead to adjustments in the study design or objectives.

Example: Consider a hypothetical RCT aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of a new educational program in improving literacy rates among primary school children. The expected improvement is a 10% increase in literacy rates. A power analysis might indicate that 200 students per group (intervention and control) are needed to detect this difference with 90% power and a significance level of 0.05. However, if the recruitment proves challenging, the researcher might decide to reduce the power to 80%, which would lower the required sample size, or to adjust the expected effect size based on preliminary data.

sample size considerations are integral to the design of any study and must be tailored to the specific research question and study design. A well-justified sample size enhances the credibility of the study findings and ensures that the research can contribute meaningful knowledge to the field.

Sample Size Considerations for Different Study Designs - Sample Size Determination: Optimizing Sample Size: A Critical Factor for Accurate Experimental Data

7. Adjusting Sample Size for Population Variability

When embarking on a research project, one of the most crucial decisions a researcher must make is determining the appropriate sample size. This decision is not merely a matter of choosing a number large enough to give the study power or small enough to be feasible; it is about adjusting the sample size to account for the variability within the population being studied. Population variability, which refers to how much the members of the population differ from one another, can significantly impact the accuracy and reliability of the experimental data.

1. Understanding Population Variability: Before adjusting sample size, it's essential to understand the concept of population variability. In statistics, this is often quantified by the standard deviation or variance. A population with high variability will require a larger sample size to ensure that the sample accurately reflects the population.

Example: Consider a clinical trial testing a new drug. If the response to the drug varies greatly among patients (high variability), a larger sample will be needed compared to a scenario where the response is more uniform (low variability).

2. Estimating Variability: Researchers often use pilot studies or historical data to estimate the variability in the population. This preliminary data helps in calculating the required sample size using statistical formulas.

Example: A pilot study with 30 participants might show a standard deviation of blood pressure readings. This estimate can then be used to calculate the sample size needed for the full-scale study.

3. The Role of confidence intervals: confidence intervals are another tool that researchers use to account for variability. The width of the confidence interval reflects the uncertainty in the estimate; a wider interval suggests more variability and, hence, the need for a larger sample size.

Example: If a researcher desires a narrow confidence interval to ensure precise estimates, they will need a larger sample size to decrease the interval's width.

4. Using power analysis: Power analysis is a method used to determine the sample size required to detect an effect of a given size with a certain degree of confidence. It takes into account the population variability and helps ensure that the study is neither over- nor under-powered.

Example: A power analysis might reveal that to detect a 5 mmHg difference in blood pressure with 80% power, a sample size of 200 might be necessary.

5. Adaptive Sample Size Techniques: Some advanced statistical techniques allow for the adjustment of sample size during the study based on interim results. This can be particularly useful in long-term studies where initial estimates of variability may change.

Example: In a long-term study on the effects of diet on health, researchers might adjust the sample size at predefined intervals based on the observed variability in health outcomes.

Adjusting the sample size for population variability is a dynamic process that requires careful consideration of statistical principles and the specific context of the study. By doing so, researchers can optimize their sample size to achieve accurate and reliable results, which is the cornerstone of any successful experimental endeavor.

8. Software and Tools for Sample Size Estimation

In the realm of experimental research, the estimation of an appropriate sample size is a pivotal step that can significantly influence the validity and reliability of the results. The process of determining the right sample size requires careful consideration of various factors, including the expected effect size, desired power, significance level, and population variability. To aid researchers in this complex task, a plethora of software and tools have been developed, each designed to simplify and streamline the process of sample size determination.

1. GPower: A widely recognized tool, GPower, offers researchers the ability to perform a range of power analyses for different study designs. For example, when planning a study to compare two means, G*Power can calculate the minimum sample size required to detect a specified effect size with a given power and alpha level.

2. PASS (Power Analysis and Sample Size): PASS is another comprehensive tool that provides sample size calculations for over 920 statistical test and confidence interval scenarios. It's particularly useful for more complex study designs, such as cluster-randomized trials or studies with multiple endpoints.

3. NQuery: This software is renowned for its advanced features that cater to clinical trial designs. NQuery offers solutions for traditional fixed-sample designs as well as adaptive and Bayesian approaches, accommodating the evolving needs of clinical research.

4. SAS/STAT: For users of SAS, the SAS/STAT module includes procedures for power and sample size analysis. Researchers can utilize these procedures to plan, analyze, and graphically display the results of statistical power analyses.

5. R Packages: The R statistical environment, being open-source, has numerous packages dedicated to power and sample size calculations, such as 'pwr' and 'powerMediation'. These packages are constantly updated by the community, ensuring they remain relevant and incorporate the latest statistical methodologies.

6. Sample Size Calculators Online: There are various web-based calculators that provide quick estimates of sample sizes for simpler study designs. These are particularly handy for preliminary assessments or educational purposes.

To illustrate the practical application of these tools, consider a scenario where a researcher is investigating the effect of a new educational intervention on student performance. Using G*Power, the researcher might determine that to detect a small to medium effect size with 80% power at a 5% significance level, a sample of 200 students would be required. This estimation can then guide the recruitment process and ensure that the study is adequately powered to detect meaningful differences.

The selection of a sample size estimation tool should be guided by the specific requirements of the study design and the researcher's familiarity with statistical concepts. By leveraging these tools, researchers can enhance the rigor of their experimental designs and contribute to the production of robust and credible scientific evidence.

9. Best Practices and Ethical Considerations in Sample Sizing

Determining the appropriate sample size is a pivotal aspect of experimental design that directly impacts the validity and reliability of research findings. Best practices in sample sizing are guided by statistical principles, ethical considerations, and practical constraints. From a statistical standpoint, a sample should be large enough to provide sufficient power to detect a meaningful effect, but not so large as to waste resources or unnecessarily expose subjects to potential harm. Ethically, researchers are obligated to respect the principles of beneficence, minimizing harm, and justice, ensuring that the benefits and burdens of research are distributed fairly.

From the perspective of different stakeholders, the considerations vary. A statistician might emphasize the importance of power analysis and effect size, while an ethicist might focus on the implications of over- or under-recruitment. A project manager, on the other hand, might be concerned with the logistical aspects of recruiting the necessary number of participants within the constraints of time and budget.

Here are some in-depth points to consider:

1. Statistical Power and Effect Size: The sample size should be determined based on the desired statistical power, usually set at 80% or higher, and the expected effect size. For example, if a clinical trial is testing a new drug, the sample size must be large enough to detect a clinically significant improvement in outcomes compared to a placebo.

2. Ethical Recruitment: Participants should be recruited ethically, avoiding coercion or undue influence. This includes transparent communication about the study's purpose, risks, and benefits.

3. Population Representation: The sample should represent the population to which the results will be generalized. For instance, if a study aims to understand a phenomenon in a particular age group, the sample should proportionately include individuals from that age bracket.

4. Minimizing Harm: Researchers must design studies to minimize physical, psychological, or social harm to participants. This could mean limiting invasive procedures or ensuring confidentiality to protect sensitive information.

5. Resource Allocation: Consideration must be given to the efficient use of resources. Overestimating the needed sample size can lead to unnecessary costs and resource allocation, while underestimating can result in inconclusive results.

6. Adaptive Design: In some cases, an adaptive design may be used where the sample size is adjusted based on interim results. This approach can be more efficient and ethical but requires careful planning and justification.

7. Regulatory Compliance: Researchers must adhere to regulatory requirements and guidelines, which may dictate minimum or maximum sample sizes for certain types of studies.

To illustrate these points, let's consider a hypothetical study on the effectiveness of a new educational program. The researchers conduct a power analysis and determine that a sample size of 200 students is needed to detect a significant improvement in test scores. They ensure a diverse recruitment strategy to represent the student population accurately and design the study to minimize disruptions to the students' regular learning activities. Throughout the study, they remain vigilant to the ethical treatment of participants and adjust their sample size in response to preliminary findings, all while staying within the bounds of educational regulations and guidelines. This approach exemplifies the multifaceted nature of sample sizing and the balance between scientific rigor and ethical responsibility.

Best Practices and Ethical Considerations in Sample Sizing - Sample Size Determination: Optimizing Sample Size: A Critical Factor for Accurate Experimental Data