Rising Inflation Expectations: Bad News or Good News?

By way of full disclosure, I should note that it’s clearly good news for me, since I’m short nominal Treasury notes. If you follow the logic, that means it’s in my interest to convince other investors that conditions are more inflationary than I really think they are, so while the main point of my last post still stands, you should probably take the caveats (“There's little question that the expected inflation rate has risen...”) with a grain of salt. (Rising inflation expectations are clearly good news for me, but if this is what the good news looks like, I’d hate to see what happens to nominal yields when inflation expectations are falling!)

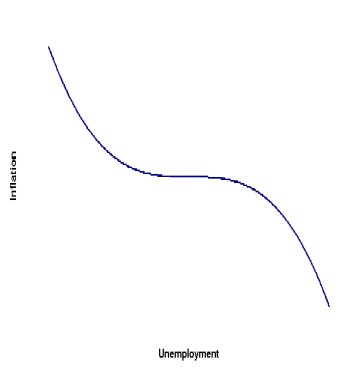

As to the “general interest,” however, the most obvious interpretation is that rising inflation expectations are bad news, because they mean that markets have lost confidence in the Fed’s willingness to keep inflation within its perceived target range. Or, as Greg puts it (quoting the Cleveland Fed’s Web server and adding a double entendre), “the system ‘has experienced an unexpected error.’” If the market loses confidence in the Fed’s inflation target, then, theoretically, the change in the expectations term in the Phillips curve causes it to shift upward, and we can anticipate both higher unemployment rates (in the short run) and higher inflation rates (in both the short run and the long run, unless confidence is eventually restored) than we would otherwise experience at any given level of aggregate demand.

Under that interpretation, the higher unemployment rates in the short run are clearly bad news. As for the higher inflation rates, I’m not so sure. A slightly different, but related, interpretation is that the market correctly perceives that the Fed has finally come to its senses and raised its inflation target from an unreasonably low level. Indeed, the current crisis, in which reasonable people are worried both about inflation becoming unhinged and about a potential deflationary collapse, is a good demonstration of why the target should be higher. It is kind of hard to believe that the Fed has come to its senses, though, since the rest of the world’s major central banks have been even further from their senses than the Fed.

Even if you think the Fed’s perceived* inflation target (between 1.75% and 2% on the personal consumption deflator, which is maybe about 2.25% to 2.5% on the CPI) is reasonable, you might think there are certain situations where the target should be raised. One of those situations might be a “safety trap” – where investors shun all but ultra-safe assets, even when the expected returns become much lower than those on risky assets. Arguably (though the argument becomes much weaker when you look at the stock market instead of the credit markets) the US is experiencing a safety trap now, and one solution is to take away the safety of the supposed safe asset by promising to inflate away the returns to be earned by government bondholders. Another situation where raising the target might be a good idea is when the uncertainty around the expected inflation rate increases, so that pursuing the original target would produce a significant risk of deflation. There might be a fairly strong case (as I suggest in the previous paragraph) that the US is in that situation right now. Obviously if you think that current circumstances call for an increase in the inflation target, then it is good news to learn that (in the judgment of the market) the target has actually increased.

But all these interpretations assume that the general shape of the distribution of inflation possibilities remains roughly the same. Moreover, casual talk of “expected inflation” suggests that we think the mean and the median of the distribution are roughly the same, since “expected inflation” could refer to either one. But perhaps what has happened is that the mean of the distribution has risen but the median has not. I would interpret the Fed’s target more as a median than as a mean. I would certainly hope that it isn’t the mean, and that the Fed would be more willing to tolerate inflation rates 3% above its target (high by recent standards but far from disastrous) than rates 3% below its target (deflation, which could be disastrous). Under this interpretation, the market still has confidence in the Fed’s target as a median, but the market is reassured that extremely low inflation rates will not be tolerated, so that the distribution has become more skewed to the right, and the mean has risen. In that case, the increase in mean (but not median) inflation expectations is good news.

[UPDATE: Paul Krugman, using what seems to be another species of the "in this situation, the inflation target should be raised" argument, makes the case that high inflation expectations are good news.]

*The Fed has actually announced a 3-year-ahead forecast, which can perhaps be reasonably interpreted as a target.

Labels: economics, inflation, macroeconomics, Mankiw, monetary policy, Phillips curve, US economic outlook