Several issues arise in the light of

Mark Thoma’s post about

my last post. First, there is the distinction between labor cost targeting and wage targeting. Mark brings up the general argument for targeting sticky prices and/or wages (in particular as presented by Michael Woodford). To the extent that wages are stickier than prices, the theoretical argument would call for targeting wages, if one wants a simple policy (although more generally it should be an index of most wages and some prices). The problem with targeting wages is that it makes the inflation rate less predictable by taking away its long-term anchor. If productivity grows quickly, a wage targeting policy would imply a very low rate of price inflation (possibly even deflation); whereas if productivity grows slowly, a wage targeting policy would imply a higher rate of inflation. Productivity growth is notoriously difficult to forecast over long horizons, so the details of the long-term inflation rate become a wild card. I’m not sure I have a theoretically sound argument, but something about having an indeterminate long run inflation rate makes me uncomfortable. Certainly it has the disadvantage of making it harder to price long-term bonds.

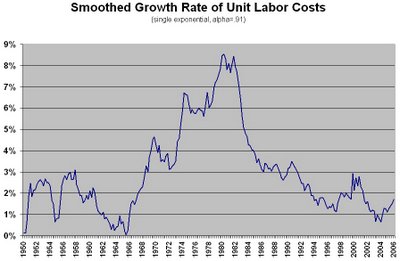

In contrast, targeting labor costs would only permit temporary variations in the inflation rate in response to external supply shocks or distribution shocks. For example, a large increase in import prices would cause the inflation rate to rise in the short run, but eventually the domestic price level will adjust, and the inflation rate will go back to its long-run path. It’s true that the relevant long run could be very long: for example, the inflation rate has been higher than the labor cost growth rate for most of the last 16 years, as the chart in my last post shows, because the distribution of income has been shifting gradually toward capital. We don’t know if that shift will continue or reverse or how much longer it might continue, but we can be sure it will end eventually, because income shares can only vary between 0% and 100%. (Historically, income shares have in fact been mean-reverting. Possibly we are in a new regime now in which there has been a permanent increase in capital’s share, but for practical purposes, even if we can’t be sure it will mean-revert, I think we can rule out a large permanent increase in capital’s share beyond its current near-record.)

Which brings me to another point I wanted to make. Several people have objected that targeting labor costs would mean putting a limit on wage growth, potentially further shifting income toward capital. I would call this a “glass half empty” view of labor cost targeting. The “glass half full” view is that labor cost targeting would

insist on wage growth (up to a point). Since we’re talking about nominal wages, it’s not clear to me that either of these two views really has much substance to it: no matter what happens to nominal wages, prices can still change in such a way as to render real wages either higher or lower.

It has been suggested that, if the Fed were programmed to react to large wage gains by tightening, that would give workers less bargaining power. But if you look at the past 15-20 years, it looks like the Fed might have been targeting inflation at around 2%; if instead the Fed had targeted labor cost growth at 2%, that means the Fed would have tolerated even larger wage gains than it actually did, so presumably workers would have had more bargaining power than they actually did.

I’m not inclined to give much credence to these kind of arguments about bargaining power anyhow, because the Fed would be targeting

aggregate labor costs, whereas wage bargains are made in individual industries (or at individual firms, or, these days, more likely by individual firms dealing with individual workers). If, for example, auto workers are somehow magically able to bargain for a 20% wage increase, the Fed need not necessarily react, unless it expects workers in other industries to get the same wage increase. I don’t see how there is much loss of bargaining power.

It’s also important to realize that labor cost targeting does not necessarily mean reacting directly to labor cost growth in the short run. As I pointed out in my last post, the data in the short run are unreliable, and it wouldn’t be appropriate to put too much weight on recent data that could be revised or could be just a temporary blip. So even if everyone gets a huge wage increase, the Fed’s reaction might be delayed. In general, workers could probably expect enough delay in the Fed’s reaction to make them comfortable driving as hard a bargain as their particular circumstances seem to warrant, since the tightening might well come later on when employers are trying to raise prices instead of when the actual wage increases happen.

Furthermore, to some extent labor costs have a predictable business cycle pattern, and big increases in labor costs are more likely to precede a recession. Since the Fed would want to dampen rather than amplify the business cycle, it would not be well advised to tighten in direct response to a cyclical increase in labor costs. Rather, it should have a forecast of the cyclical behavior of labor costs, and it should tighten or loosen depending on what labor costs do relative to that expected cyclical behavior. Realistically, though, the forecast should also include a lot of other indicators, and the Fed would be concerned with the

ultimate level of labor costs at some point in the future. Though unexpected cyclical behavior would be a reason to revise that longer-term forecast of labor costs, it might well be offset by other reasons relating to the other indicators involved.

UPDATE: Another point occurs to me, which sort of ties together some of the points above. With wage targeting, the "damaged bargaining power" school might have a stronger case, because wage targeting would attempt (though with only limited likely success over any short time horizon) to put a constraint -- one that could be anticipated in advance -- on the aggregate behavior of wages at any particular time. With unit labor cost targeting, there is no absolute intended constraint on wage growth, because the intended wage growth would depend on productivity growth, which (a) could not be known in advance, (b) would not be known with any reliable precision until quite a bit later, and (c) might well depend on other aspects of labor negotiations, or for that matter, on wages themselves.

Labels: economics, income distribution, inflation, labor, macroeconomics, monetary policy, wages