Academic writing part 1

- 2. Academic writing Part 1 By: M. H. Farjoo M.D, Ph.D, Statistics Lecturer, Bioanimator Pharmacology Dep., Faculty of Medicine, SBMU

- 3. Academic writing (Part 1) How to Start Generalizations and Cautious Style Title Abstract Keywords Introduction Methods Results Discussion Conclusion Acknowledgements References Supporting Information Read the Text out to Yourself Publishing Ethics Cover Paper Questions of Reviewers Delay in Publishing What to do with Rejection? Letters to the Editor Posters

- 4. How to Start Establish one or a few regular places in which to work. Minimize distractions and limit social interruptions. Make writing a daily activity and write while fresh. Write in small, regular amounts, and avoid ‘binge sessions’. Schedule writing tasks in small sizes in order to keep up. of 604Slide

- 5. How to Start Make ideas on the back of an envelope, or record on your phone. Share your writing with supportive, constructive friends. Do not aim for perfection on the first draft. Let it flow, and then come back to polish it. Start by reading what you have produced so far, and rephrase things. of 605Slide

- 6. How to Start Make a note of the structure of the text you want to write and list its main headings, then work to these. Do NOT stop writing at the end of a section. Write one or two sentences of the next one and then finish. Do not stop to correct and revise. Keep going and then come back to do this later. Reward yourself for meeting your targets. of 606Slide

- 7. How to Start The hallmarks of scientific writing are precision, clarity and brevity, in that order. Try to write as if you were speaking to someone: “see a face”. Write (your chapters) in four drafts: 1. Putting the facts together 2. Checking for coherence and fluency of ideas 3. Readability 4. Editing of 607Slide

- 8. How to Start Start writing your Experimental Chapters first. If you have done a Literature Review, write it next. Then complete the rest: Conclusions, Introduction, and Summary, in that order. The other bits and pieces like the Appendices may be written as you go along. In the whole article try to use the first, rather than the third person: ‘We suggest. . .’ instead of: ‘This paper suggests . . .’ of 608Slide

- 9. of 609Slide | 9 Title Authors Abstract Keywords Structure of Scientific articles: Main text • Introduction • Methods • Results and discussion • Conclusion Acknowledgements References Supplementary material

- 10. of 6010Slide | 10 Correct article structure: Figures /Tables (your data) Methods Results Discussion Conclusion Introduction Title,Abstract & Keywords

- 11. Generalizations and Cautious Style Generalizations are often used to give a simple introduction to a topic: The majority of smokers in Britain are women. Of all UK smokers, 56.2% are women and 43.8% are men. Although the second sentence is more accurate, the first is easier to understand and remember. of 6011Slide

- 12. Generalizations and Cautious Style Generalizations can be made in two ways: Using the plural: Computers have transformed the way we live. Using the singular + definite article (more formal): The computer has transformed the way we live. You must avoid using generalizations that cannot be supported by evidence e.g.: Students tend to be lazy. of 6012Slide

- 13. Generalizations and Cautious Style A cautious style is necessary in academic writing to avoid statements that can be contradicted: Demand for healthcare usually exceeds supply. Most students find writing exam essays difficult. Fertility rates tend to fall as societies get richer. of 6013Slide

- 14. Generalizations and Cautious Style Avoid absolute statements such as: unemployment causes crime. Smoking causes lung cancer. Instead, use cautious style: Unemployment may cause crime or tends to cause crime. Smoking can cause lung cancer. Avoid adverbs that show your personal attitude: luckily, remarkably, surprisingly, interestingly. of 6014Slide

- 15. Generalizations and Cautious Style Areas where caution is particularly important include: Outlining a hypothesis that needs to be tested (e.g. in an introduction). Discussing the results of a study, which may not be conclusive. Commenting on the work of other writers. Making predictions (normally with may or might). of 6015Slide

- 16. Generalizations and Cautious Style Caution is also needed to avoid making statements that are too simplistic: Crime is linked to poor education. Caution can be shown in several ways: Crime may be linked to poor education. Crime is frequently linked to poor education. Crime tends to be linked to poor education. of 6016Slide

- 17. Generalizations and Cautious Style Another way to express caution is to use quite, rather or fairly, before an adjective: A fairly accurate summary A rather convenient location Quite a significant discovery Quite, is often positive, while rather, tends to be negative. Quite = Pretty Rather = Fairly of 6017Slide

- 18. Titles Reviewers do not like titles that fail to represent the subject matter adequately. If the title is not accurate, the appropriate audience may not read your paper. of 6018Slide

- 19. Abstract The abstract is often written last, together with the title. Structured abstracts are typically written using five sub-headings: Background Aim Method Results Conclusions of 6019Slide

- 20. Abstract The quality of an abstract will strongly influence the editor’s decision. The abstract summarizes in 50-300 words the problem, the method, the results and the conclusion. The abstract gives sufficient details so the reader can decide whether or not to read the whole article. Write the abstract last so it accurately reflects the article. of 6020Slide

- 21. Keywords Keywords ae very important for indexing: they help your article to be more easily identified and cited. Keywords should be specific, so avoid uncommon abbreviations and general terms. Check guide-for-authors of your target journal for specific keyword policy. Check Scopus to see how your peers use Keywords, search for your subject area, filter results by keyword. of 6021Slide

- 22. Keywords To produce effective key words: 1. Use simple, specific noun clauses. For example, use variance estimation, not estimate of variance. 2. Avoid terms that are too common, otherwise the number of ‘hits’ will be too large to manage. 3. Do not repeat key words from the title. These will be picked up anyway. of 6022Slide

- 23. Keywords To produce effective key words: 4. Avoid unnecessary prepositions, especially “in“ and “of”, e.g. use: “data quality” rather than “quality of data”. 5. Avoid acronyms, they may be puzzling. 6. Spell out Greek letters and avoid mathematical symbols, they are impractical for computer-based searches. of 6023Slide

- 24. Keywords To produce effective key words: 7. Use the names of people if only they are part of a terminology, e.g. Poisson distribution. 8. Include alternative or inclusive terminology which encompasses all different forms of the concept. of 6024Slide

- 25. of 6026Slide | 26 Funnel shape of a typical introduction. Schematic depiction of the sequential flow of questions to be addressed in the introduction

- 26. Introduction Provide a brief context to readers. Address the problem. Identify the solutions and limitations. Identify what the work is trying to achieve. Provide a perspective consistent with the nature of journal. Write a unique introduction for every article. DO NOT reuse introductions! of 6028Slide

- 27. Introduction Introductions are usually no more than %10 of the total length of the assignment. An effective introduction explains the purpose and scope of the paper to the reader and has 3 stages. Stage 1: establish a research territory: By showing that the general research area is important, central, interesting, problematic or relevant in some way (optional). By introducing and reviewing items of previous research in the area (obligatory). of 6029Slide

- 28. Introduction Stage 2: establish a ‘niche’ by indicating a weakness in the account so far. Indicate a gap in the previous research. Raise a question about it. Extend previous knowledge in some way (obligatory). of 6030Slide

- 29. Introduction Stage 3: occupy the niche by saying they are going to put this right: By outlining the purposes or stating the nature of the present research (obligatory). By listing research questions or hypotheses to be tested (optional). By announcing the principal findings (optional). of 6031Slide

- 30. Methods Describe how the problem was studied. Include detailed information. Do not describe previously published procedures. Identify the equipment and materials used. Approval of the ethics committee should be specified in the manuscript, and covering letter. of 6033Slide

- 31. Methods Method sections are usually subdivided (with subheadings) into three sections: 1. Participants 2. Measures 3. Procedure(s) Write the method in such a way that readers can repeat the method from the descriptions given. A useful device for clarifying the method for the reader is to summarize it in a table or figure. of 6034Slide

- 32. Results Include only data of primary importance. Use sub-headings to keep results of the same type together. Be clear and easy to understand. Highlight the main findings. Feature unexpected findings. Provide statistical analysis. Include illustrations and figures. of 6035Slide

- 33. Results The art of writing good results is to take the readers through a story. You can present the results in several ways: State the main findings in order. State the subsidiary findings. An interweaving of the above– the first set of main findings and related subsidiary ones, followed by the second set, and so on. of 6036Slide

- 34. Discussions Discussion should correspond to the results. Compare published results with your own. Be careful NOT to use the following: Statements that go beyond what the results can support. Non-specific expressions. New terms not already defined or mentioned in your paper. Speculations on interpretations based on imagination. of 6037Slide

- 35. Discussions There are 5 steps for discussions: 1. Restate the findings and accomplishments. 2. Evaluate how the results fit with the previous findings – do they contradict, agree or go beyond them? 3. List potential limitations to the study. 4. Offer an interpretation of these results and ward off counter-claims. 5. State the implications and recommend further research. of 6038Slide

- 36. Conclusion The conclusion should provide a clear answer to any question asked in the title. It should summarize the main points. Provide justification for the work. Do not repeat exactly what has been written in preceding sections. Explain how your work advances the present state of knowledge. Suggest future experiments. Do not over-emphasize your work. of 6039Slide

- 37. Acknowledgements Financial. instrumental/technical, e.g. statistical analysis. Conceptual, e.g. critical insight. Editorial, e.g. bibliographic assistance. Proof readers and typists. Suppliers who may have donated materials. Moral, e.g. the support of family. of 6040Slide

- 38. References Do not use too many references. Always ensure you have fully absorbed the material you are referencing. Avoid excessive self-citations. (how many are OK?) Avoid excessive citations of publications from the same region or same institute. Conform strictly to the style given in the “Guide for Authors”. of 6041Slide

- 39. Supporting Information Extensive descriptions, experimental details, analyses and datasets can be submitted as a separate file. They will be peer-reviewed and published with article. of 6042Slide

- 40. Labelling The word ‘figure’ is used for almost every visual information (maps, charts and graphs) except tables. Titles of tables are written above, while titles of figures are written below the data. As with other data, sources must be given for all visual information. of 6043Slide

- 41. Read the Text out to Yourself Reading the text out to oneself is a useful way of seeing how well the text flows. Ask other people to read your drafts. Never regard the last version of the text as the final one. Put this version on one side and then come back to it a day or two later. Seeing the text with fresh eyes somehow suggests further changes, but draw the line eventually! of 6044Slide

- 42. Publishing Ethics To avoid plagiarism 3 technics are used: Paraphrasing: rewriting a text while the content stays the same. Summarizing: reducing the length of a text but retaining the main points. Both of the above! of 6045Slide

- 43. Publishing Ethics Unacceptable issues are: Using exact phrases from the original source without enclosing them in quotation marks Emulating sentence structure even when using different words Emulating paragraph organization even when using different wording or sentence structure of 6046Slide

- 44. Publishing Ethics Correct Citation Is the Key! Crediting the work of others (including your own previous work) by citation is important for 3 reasons: To place your own work in context. To acknowledge the findings of others on which you have built your research. To maintain the credibility and accuracy of the scientific literature. of 6047Slide

- 45. Cover Paper This is your opportunity to convince the journal editor that they should publish your study. Take that opportunity! Briefly describe: Yourself: your background, expertise research area, track record Describe the research field, main developments, key- players The main findings of this research and what is new The significance of this research The significance and relevance for journal of 6048Slide

- 46. Cover Paper Refer to previous papers on same topic in the journal. Keep it brief, but convey the particular importance of your manuscript to the journal Suggest reviewers from different institutes/countries, describe why you suggest them (e.g. their specific expertise). Mention who should not review your paper and explain why. of 6049Slide

- 47. of 6050Slide | 50 Dear Sir, The development of this class of compounds is a very active field of chemistry these days. We have studied these materials for many years and have published six papers on synthesis and properties…. Important contributions in this field have been made by…. Also in your journal several papers have focused on elucidating the mechanism of …. A better understanding of this phenomena will lead to more environmentally-friendly…. Our laboratory has developed a specific technique that has enabled us to study …. Prof. Smith would be a suitable reviewer due to his expertise in… Cover Paper of 6050Slide

- 48. Questions of Reviewers Be prepared for common questions to reviewers. Editors want to know if a certain paper is worth publishing. They want to know if: Paper is scientifically correct. If it reports something new. If it reports something significant. If the paper is of interest to the readers. of 6051Slide

- 49. Questions of Reviewers Does the topic of the paper fit within the journal? Are title and abstract in line with content? Is the introduction clear, balanced and well organized? Are experiments correct? Can they be repeated based on description? of 6052Slide

- 50. Questions of Reviewers Comment on quality of tables/figures/images. Are the results well-presented and analyzed? Is research put in appropriate context? Are references accurate, up-to-date, balanced, accessible? Comment on importance, validity, generality of conclusions of 6053Slide

- 51. Solutions for Delay in Publishing Always have other papers ‘on the go’, while awaiting editors’ decisions. Ask the editor whether your paper is appropriate for the journal before submitting it. of 6054Slide

- 52. What to do with Rejection? Calm down! which may take 2 weeks! Revise the manuscript than just sending it without changes to another journal. Meet requirements of the new journal, as well as to pre- empt the criticisms made by the original referees. Keep working on your papers after submitting, especially if they come across some new and relevant findings. This will help to respond to any referees’ criticisms. of 6055Slide

- 53. Letters to the Editor Remind the reader of the contents of the paper to be commented on. Raise the explicit criticism. Give evidence for the criticism. Urge colleagues not to take at face value the specific point made in the earlier paper. of 6056Slide

- 54. Letters to the Editor For answering the letters to the editor, use: Belittling the point to which your are responding (e.g. poorly conceived, mistaken, not well thought out, inappropriate, unsupported). ‘Boosters’ to strengthen your own position (e.g. show clearly, demonstrate, confirm the fact that). of 6057Slide

- 55. Posters Conference organizers specify how large posters can be. The conventional size is about 120 cm by 75 cm. It is essential to find out what size is allowed before designing a poster. of 6058Slide

- 56. Have a clear, short title. Avoid acronyms in the title (and the text). Use a 24–30 point font size and try reading your poster from 90 to 180 cm away. Use no more than three columns of text and make the flow/organization of the text clear. Posters of 6059Slide

- 57. Posters Do not use all capital letters for headings, and titles. Do not underline headings. Use only one or two type font. Set the text ‘unjustified’ with equal word spacing and a ragged right-hand edge (as in this slide). Use short sentences and ‘bulleted’ lists. Do not set the text single-spaced. of 6060Slide

- 58. Posters Use one, two or at most only three colors, and only if each color has a didactic purpose. Do not use 3D graphics. Prepare a handout specifying your name, affiliation, date, and place of the presentation which can be given to people who pass by. of 6061Slide

- 62. Components and Structure of a Manuscript The objective of a scientific paper is to narrate the story with sufficient details to allow the reader to: Evaluate the interpretations derived. Reprise the research. Judge if the conclusions drawn are accurate. Components of Research Paper: Introduction (What was the question asked?) Methods (How was that studied?) Results (What were the findings?) And Discussion (What do they mean and what is their implication?) Refer to “Instructions to the Authors” page before you start writing the manuscript. of 6065Slide

- 63. Components and Structure of a Manuscript See also these links for Preparing a Manuscript for Submission to a Medical Journal: http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/manuscri pt-preparation/preparing-for-submission.html https://www.bmj.com/sites/default/files/attachments/reso urces/2018/05/BMJ-InstructionsForAuthors-2018.pdf For Systematic Reviews see: https://libguides.library.usyd.edu.au/c.php?g=516278&p= 3529739 For Critical Appraisal Tools see: https://joannabriggs.org/ebp/critical_appraisal_tools of 6066Slide

- 64. Components and Structure of a Manuscript Introduction The introduction is the first component of research publication after title and abstract. It is usually brief and communicates precisely the scope (what was the rationale and aim of the study) of the paper. It should describe the study background (the available base of knowledge), significance, and aims. It should clearly define or describe what research questions/hypothesis being tested, respectively. of 6067Slide

- 65. Components and Structure of a Manuscript Methodology: The Methodology section consists of two parts: “Materials” and “Methods.” The “Materials” section provides answer to: Who/what was examined (e.g., humans, animals, cadavers, tissue preparations)? What interventions were employed (e.g., oral, injectable, gases)? What instruments were used (e.g., HPLC, hemoglobinometers) in the study? The “Methods” section provides information on how subjects were manipulated to answer the experimental question, how measurements and calculations were carried out, and how the data were managed and analyzed. of 6068Slide

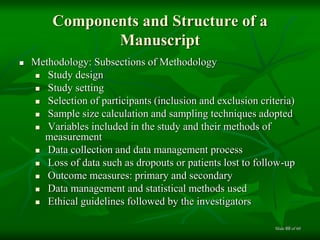

- 66. Components and Structure of a Manuscript Methodology: Subsections of Methodology Study design Study setting Selection of participants (inclusion and exclusion criteria) Sample size calculation and sampling techniques adopted Variables included in the study and their methods of measurement Data collection and data management process Loss of data such as dropouts or patients lost to follow-up Outcome measures: primary and secondary Data management and statistical methods used Ethical guidelines followed by the investigators of 6069Slide

- 67. Components and Structure of a Manuscript Methodology: It is a good practice to refer to checklists available like “Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)”: https://strobe- statement.org/index.php?id=available-checklists For articles presenting with results of randomized clinical trials see: http://www.consort- statement.org/ of 6070Slide

- 68. Components and Structure of a Manuscript The Results section is the easiest section to write. One has to describe the findingsof the intervention/observation in this section. Usually, the Results section consistsof three components: Text, Tables, and Graphs. The text should be used to conveyunique information and highlight the most important aspects of the figures andtables so that unnecessary duplication of data presented in tables and figures isavoided in the text. Only important observations need to be emphasized or summarized.The same data need not be presented both in tables and figures. It is a common mistake that the authors commit as they tend to describe the meaning/interpretation of the data in the Results section. The best part to describe the interpretation of the findings is the Discussion section. of 6071Slide

- 69. Components and Structure of a Manuscript The Discussion section: Discussion is one of the most difficult sections to write in a manuscript.The discussion provides value to the paper and compares the work of the authorswith other scientists. The discussion should deal with the interpretation (findings aresimilar/consistent with other studies or dissimilar with other reported literatures) ofresults without repeating information which has already been presented under theResults section. The discussion should review how the study observations add to thecurrent scientific literature, offer explanations for the findings, compare the study’sfindings with other literatures, and discuss the limitations and, if possible, the implicationsfor future research. The discussion usually ends with a brief summarystatement.Authors should avoid presenting general statements which are not emergingfrom the research study as conclusion. Sometimes depending upon the results, theauthors may recommend future work to be done in the area and provide way forward.This component can also be included toward the end of the Discussion section.Utmost care should be taken in drafting the Discussion section as it providesvalue to the paper. of 6072Slide

- 70. Components and Structure of a Manuscript Acknowledgment: People who don’t meet the authorship criteria should be acknowledged. Acknowledgment should be brief and intended to be made for specific scientific or technical assistance and financial support only. It is not required to acknowledge individuals for providing routine departmental facilities and not mandatory for help in the preparation of the manuscripts without actually contributing to scientific content. of 6073Slide

- 71. Components and Structure of a Manuscript References The total number of references depends upon the type and nature of the manuscript.It is always a good practice to refer to the “Instructions to the Authors” page forclear guidance. References cited should be numbered consecutively as they appearin the text and should be placed at the end of the manuscript. Style of referencingalso depends upon the journal; hence, considerable attention should be paid beforewriting references. of 6074Slide

- 72. of 6075Slide | 75 Components and Structure of a Manuscript

- 73. Title Key points: The title, abstract, and keywords often hold the key to publication success. The title of an article should be simple, precise, and catchy. The title should contain pertinent, descriptive words pertaining to the research. The three most commonly used types of titles are declarative, descriptive, and interrogative titles. Running title is an abbreviated form of the main title, usually cited at the top of each published page or left-hand text pages. Running title serves to guide a reader while scanning through a journal or toggling through multiple pages of the journal online. Title page is the first page of the manuscript which contains general information about the article and the authors. Title page generally consists of 11 main components mainly the title, running title, author names, affiliations, number of pages of the manuscript, no. of figures, tables, references, conflict of interest, source of funding, acknowledgments, and disclaimers. The covering letter is a vital document, which serves to create an important first impression on the editor. The goal of a covering letter is to convey to the editor how the manuscript meets the criteria of the journal to which it is submitted. of 6076Slide

- 74. Title There Are Three Basic Rules to Be Followed While Writing a Title: The title should be simple, precise, and catchy. The title should contain pertinent, descriptive words pertaining to the research. Avoid abbreviations/numerical parameters in the title. The title generally should not exceed 150 characters or 12–16 words, though this should be tailored to the instructions of the specific journal. The following format can be used as a rough guide for writing a title: research question + research design + population + geographic area of study (what, how, with whom, where). The last two may be excluded in case of word constraints. There is no full stop at the end of the title. of 6077Slide

- 75. Types of Titles There are 3 types: Declarative Titles – Declarative title state the main findings stated in the paper. These titles convey the most information and are the most appropriate for research articles. Descriptive Titles – Descriptive title describes the subject of the research without revealing the conclusions. It includes the relevant information of the research hypothesis which is studied (e.g., participant, intervention, control, and outcome; PICO). Interrogative Titles – Interrogative title poses the subject of research as a question. They are more appropriate for literature reviews. of 6078Slide

- 76. Types of Titles Descriptive titles are the most commonly used. A longer title is more likely to contain a given search term and is therefore identified more easily. Since most of the journals have a limit on the number words which can be used in a title. of 6079Slide

- 77. Running Title Many journals require a short title, which should not exceed 60 characters (including spaces). This is the running title/short title/running head which is an abbreviated form of the main title. Being catchy is not important for a running title; instead, clarity and precision are important. of 6080Slide

- 78. Title Page Title page is the first page of the manuscript which contains general information about the article and the authors. A title page includes the following components: 1. Title 2. Abbreviated or running title 3. Author names and affiliations and order of authorship 4. Number of pages of the manuscript 5. No. of figures, tables, multimedia, or 3D models 6. No. of references 7. No. of words in abstract, main text, and references 8. Conflict of interest 9. Sources of support 10. Acknowledgments 11. Disclaimer of 6081Slide

- 79. Title Page Only the corresponding author has the right to withdraw, correct, or make changes to the manuscript. Most of the journals have a conflict of interest declaration form. Despite this, editors will sometimes require a conflict of interest declaration on the title page. If there are no conflicts, the usual wording is “the authors declare no competing financial interests.” Any source of funding, honorarium received, or post held by any of the authors which could pose a possible conflict of interest should be mentioned. of 6082Slide

- 80. Covering Letter The goal of a covering letter is to convey to the editor how the manuscript meets the criteria required by the journal. ببین را اسالید این نویس زیر of 6083Slide

- 81. Conclusions Scientific writing should be kept simple. While writing a scientific article, you should recall more than once Einstein’s famous quote “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” Most often, maximum time and effort are spent on writing the main text of the article with little thought and effort spared for writing other parts of a research, like the title, running title, title page, and covering letter. The editor spends a relatively short time for reviewing the relevance of your work. Giving due time and consideration for these three vital parts of a research holds the key to publication success. Hence every effort must be spared to create these critical parts of the document. of 6084Slide

- 82. Abstract and Keywords Key Points: An abstract of a scientific article is a precise, clear, and stand-alone statement that provides an overview of the work to the reader and plays an important role in increasing the visibility. An effective abstract should encapsulate the essence of the article and give all essential information about the study/paper, as it’s often only the abstract that’s scrutinized by potential readers and reviewers. An abstract can be descriptive or informative. Informative abstracts can again be divided as structured and unstructured abstracts. The components of an abstract are introduction/background, methods, results, and conclusion. The discussion is not necessarily a part of the abstract unless specified. Results followed by methods should be the main emphasis of the abstract. The title of an article is keyed and hence the specific words/phrases that are used repeatedly in the manuscript can be used as keywords. of 6085Slide

- 83. Abstract and Keywords A good abstract is important for numerous reasons which can be summarized as “selection and indexing” [3]. Many a times an abstract is the only component of the manuscript that is read by the readers while doing an electronic database search or while leafing through the printed journals [2]. Very often, articles are cited solely based on abstracts. The abstract is sometimes the only part that is scrutinized by reviewers for journals or selection for presentation in conference platforms. The abstract sets the tone and entices the potential readers to gain access to your full work. Hence it should encapsulate the essence of the article and give all essential information about the study/paper. of 6086Slide

- 84. Abstract and Keywords There are 2 types of abstracts: Descriptive: used in social science and humanities. Informative: used for scientific papers with 250–300 word. It is usually one-tenth the length of the original manuscript, and has 2 types: Unstructured: there are no pre-labeled sections in the abstract. However, all the details required in the abstract are included similar to a structured abstract. This is more commonly used for case reports rather than original articles. Structured: The layout of these abstracts has distinct and labeled sections. structured abstracts are now the preferred layout It is important to note that although an abstract is a reflection of the paper, the discussion is not a part of an abstract. of 6087Slide

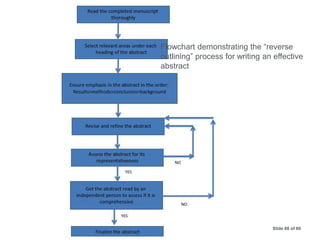

- 85. of 6088Slide | 88 Flowchart demonstrating the “reverse outlining” process for writing an effective abstract

- 86. How to Avoid Pitfalls in Abstract? Avoid the direct use of abbreviations, as it will require explanation, which will unnecessarily use up space for other relevant information. Avoid jargon and superfluous vocabulary in the abstract to avoid confusion among the readers. Do not include any references or citations while writing the abstract. Importantly, there should not be any misleading speculations stated in the abstract. of 6089Slide

- 87. of 6090Slide

- 88. of 6091Slide

![Abstract and Keywords

A good abstract is important for numerous reasons which

can be summarized as “selection and indexing” [3].

Many a times an abstract is the only component of the

manuscript that is read by the readers while doing an

electronic database search or while leafing through the

printed journals [2]. Very often, articles are cited solely

based on abstracts. The abstract is sometimes the only

part that is scrutinized by reviewers for journals or

selection for presentation in conference platforms. The

abstract sets the tone and entices the potential readers to

gain access to your full work. Hence it should

encapsulate the essence of the article and give all

essential information about the study/paper.

of 6086Slide](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/academicwriting1stpart21azar1398-200209114104/85/Academic-writing-part-1-83-320.jpg)