Concepts of structural change Lecture Universidad Computense Madrid 2019

- 1. CONCEPTS OF STRUCTURAL CHANGE: MAINSTREAM, HETERODOX AND MARXIST CONCEPTIONS AND THE GREEK CRISIS Stavros Mavroudeas Dept. of Social Policy Panteion University E-mail: s.mavroudeas@panteion.gr Máster Universitario en Economía Internacional y Desarrollo 24/4/2019

- 2. Conceptions of Structural Change & the 2008-10 Greek Crisis I. The concept of Structural Change in economic analysis and policy II. Competing explanations of the 2008-10 Greek crisis III. Structural reforms and the issue of the productive model in the Greek crisis

- 3. I. Structural Change in economic analysis and policy ▪A central issue in economic analysis and policy: Prerequisite for ushering economic development and growth ▪It permeates economic analysis from its very beginning as it touches upon critical historical economic transformations. Examples: ➢The transition from feudalism to capitalism ➢The modernization (industrialization) of capitalist economies (e.g. Lewis model) ➢The attempts for a transition to socialist economy (e.g. Preobrazhensky model)

- 4. From the structural change of developmentalism to the structural reforms of the Washington Consensus ▪ Its high time: after the 2nd WW and till the 1973 global capitalist crisis ➢ A stellar example: Latin American Structuralism (and ISI [Import Substituting Industrialisation]) and broadly speaking Developmentalism (also in the East Asia) ➢ Its dominant conception: change in the production structure through activist and discrete state policies ➢ Industrial policy: a crucial component of these state policies. Industrial policy was conceived as a heavy toolbox of vertical measures with strong asymmetrical impact on different sectors and branches of the economy ▪ Activist theories and policies of structural change stall after the 1973 global crisis: ➢ Preoccupation mainly with inflation and stabilization rather than growth ➢ The long march of developing economies halted

- 5. ▪ With the onset of Neoliberalism the concept of structural change fell behind. Activist state policies promoting radical structural transformations were considered ineffective and obstructing the normal operation of the market forces ➢ Similarly, industrial policy fall completely from grace: synonymous with ‘pork barrel politics’, ‘corporate welfare’ and, worst of all, ‘picking winners’ (R. Wade, (2014) “The paradox of US industrial policy: the developmental state in disguise”, in J.M. Salazar-Xirinachs et al., Transforming Economies: making Industrial Policy Work for Growth, Jobs and Development, UNCTAD and ILO, Geneva) – Distorts the normal functioning of free market ➢ A dogmatic rejection: ‘The best industrial policy is none at all’ (Becker, G. 1985. “The best industrial policy is none at all”, Business Week, 25 Aug.) ➢ Nevertheless, behind the Neoliberal denunciations of state economic intervention the state never actually left: its heavy hand was always present when needed. Only its interventions became more covert and more heavily pro-capitalist oriented.

- 6. ▪ As soon as Neoliberalism run into troubles in the end of the 1990s, there was an abrupt return to emphasise structural change: in order for Neoliberalism to work the economic structure must change radically (New Classicals etc.): Structural reforms became the name of the game ➢ Concomitantly, and as peripheral crises (Mexico, East Asia etc.) and international rivarlies (imperialist conflict) were fomented, there was a gradual drift towards some mild version of industrial policy ➢ However, the industrial policy of Neoliberalism preached – at least in principle – its horizontalist and non-discrete character (as opposed to the vertical and discrete industrial policy of Developmentalism) ➢ These mutations were codified in the Washington Consensus, that is the Neoliberal mandra for developing and less developed economies. The post- Washington Consensus that followed adhered to the same strategic principles; although slightly modified towards a more-down-to-earth neoconservatism (and essentially a fusion with New Keynesianism resembling to the New

- 7. ➢The Washington Consensus (Mavroudeas S. & Papadatos D. (2007), ‘Reform, Reform the Reforms or Simply Regression? The 'Washington Consensus' and its Critics’, Bulletin of Political Economy vol.1 no.1) prescriptions are codified as follows: 1) The imposition of fiscal discipline. 2) The redirection of public expenditure priorities towards other fields. 3) The introduction of tax reforms that would lower marginal rates and broaden the tax base. 4) The liberalization of the interest rate. 5) A competitive exchange rate. 6) The liberalization of the trade 7) The liberalization of inflows of foreign direct investment. 8) The privatization of state-owned economic enterprises. 9) The deregulation of economic activities. 10) The creation of a secure environment for property rights.

- 8. ▪ The Washington Consensus strategy guides IMF’s new breed of programmes: the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) of the 1990s: ➢These are a modification of the traditional IMF programmes because of (a) ascendancy of neoliberalism and (b) the associated proliferation of b-o-p crises (since the initiation of the ‘globalization’ era) ➢The ascendancy of open-economy Neoliberalism and the concomitant deregulation of international economic processes increased the fragility of the system: b-o-p crises (e.g. Latin American, Asian and Russian crises from mid- 1980s to 1998) ➢SAPs are more intrusive than previous programmes (that adopted the ‘economic neutrality doctrine’, i.e. not meddling with borrowers’ structure and objectives, Polak, J. J. (1991) ‘The changing nature of IMF conditionality’, Princeton Essays in International Finance 184: ‘structural conditionality’ (as US promoted a structural, supply-side orientation (Kentikelenis A., Stubbs T. & King L. (2016), ‘IMF conditionality and development policy space, 1985– 2014’, Review of International Political Economy)

- 9. ➢ SAPs initial theoretical premise of the Washington Consensus was subsequently supplemented with the ‘expansionary austerity doctrine’ (initiated by Giavazzi F. & Pagano M. (1990), ‘Can Severe Fiscal Contractions Be Expansionary? Tales of Two Small European Countries’, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 5, developed by Reinhart C.M. & Rogoff K.S. (2010), ‘Growth in a Time of Debt’, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, vol.100 no.2) that maintains that, under certain limited circumstances, a major reduction in government spending by altering expectations about taxes and government spending will expand private consumption, resulting in overall economic expansion (a refutation by Herndon T.; Ash M. & Pollin R. (2013), ‘Does High Public Debt Consistently Stifle Economic Growth? A Critique of Reinhart and Rogoff’, Cambridge Journal of Economics vol.38 no.2) ➢SAPs’ pro-cyclicality: consciously deepen the crisis believing that in this way it will ‘bottom’ sooner and the rebound will also be very strong (V-shaped recovery). Mimic in a distorted way Marxism’s argument that capitalism can surpass an overaccumulation crisis only by drastic capital devalorisation (i.e. through destruction and reconstruction).

- 10. ➢ SAPs’ prescription for ailing and debt-ridden economies: (1) Fiscal consolidation (to reduce fiscal deficit) (2) Labour Market deregulation (to improve competitiveness) (3) Restructuring the economy from a public-sector based to a private-sector driven (through privatisations) (4) Currency devaluation (to improve the competitiveness) (5) Opening of the economy (to attract foreign capital) (6) Debt restructuring (to alleviate the debt burden) ➢ SAP’s structural reform aim: create an open, competitive economy relying on export-led growth and foreign direct investment ❖ A necessary underpinning: low wages ➢ After the Argentinian debacle a facelift: ‘we don’t do that anymore. Mere hypocrisy: evidence of twin processes of ‘paradigm maintenance and ‘organized hypocrisy’ (Kentikelenis et al. (2016))

- 11. A preliminary note: is there a return of state economic intervention (and active industrial policies) after the 2008 global capitalist crisis? ➢ The 2008 global crisis seems to have radically broken with the prevailing neoliberal ideology and practice concerning states’ minimal involvement in the economy (Clift, B., & Woll, C. (2012). Economic patriotism: reinventing control over open markets. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(3), 307-323) ➢ The so-called ‘revisionists’ (e.g. Wade, R. H. (2012), ‘Return of industrial policy?’, International Review of Applied Economics, 26(2), 223-239.) even declared the return of state intervention and active industrial policy

- 12. • However, what is happening is rather a typical case of mere opportunism. In the face of neoliberalism’s blatant failures, the capitalist state resurfaced covert practices that have never actually gone away (Weiss, L. (2012). The Myth of the Neoliberal State. In: Kyung-Sup, C., Fine, B., & Weiss, L. (Eds.): Developmental Politics in Transition: The Neoliberal Era and Beyond. London: Palgrave Macmillan,pp. 27-42.). • To put it simply, developed capitalist economies (in the Marxist literature branded as big imperialist powers) even during the apex of the so-called ‘globalisation’ used heavy-handed and discrete policies in their conflicts. • The post-2008 crisis era and the coming of ‘de-globalisation’ has intensified and augmented this trend. e.g. the current debate in the EU about creating European super- monopolies in order to compete with the US and China. • Nevertheless, this privilege belongs to dominant imperialisms. Less developed capitalist economies and even sub-imperialist ones (like Greece) are continuing to be within the straitjackets of the Washington Consensus.

- 13. Mainstream conceptions of structural change: a critique • Production-less (economics of circulation) • Neoliberalism’s non- discreet industrial policy: a contradiction in terms • Horizontal and following the market industrial policy • Instruments: more market-based than direct public provision Functional (horizontal) against Selective (discrete) industrial policies ❑Functional policies are the least interventionist because they are designed to support (or improve) the operation of markets in general. ❑Horizontal industrial policies promote specific activities across sectors ❑Selective (discrete) industrial policies aim at propelling specific activities or sectors) Additional differentiations: o Picking versus creating winners o Comparative-advantage conforming versus comparative-advantage- defying o Leading versus following the market UNCTAD and UNIDO (2011: 34) UNCTAD and UNIDO (2011). Economic Development in Africa Report 2011: Fostering Industrial Development in Africa in the New Global Environment. United Nations. Geneva and New York

- 14. II. Competing explanations of the 2008-10 Greek crisis • Mainstream (New Macroeconomic Consensus - fusion of Neoclassicism and New Keynesianism): emphasis on policy errors, no systemic causes, no consideration of the productive structure, OCA, TDH, no relation with global crisis (external influence). • Heterodox (post-Keynesian (PK) and Radical Political Economy perspectives): emphasis on ‘weak’ structural problems (EMU, neoliberalism), no consideration of the productive structure, taking one side or other of the TDH, weak relation with global crisis (external influence). • Marxist: emphasis on ‘deep’ structural problems (CMoP), part of the global crisis, LTV, twin deficits are a result, ‘financialisation’ not a cause ➢Some overlapping at the margins (e.g.1: non-OCA & non-rectifiable close to PK financialisation, e.g.2: class struggle & financialisation and financial expropriation refer to Marxism) ➢A concise presentation: Mavroudeas S. (2015), ‘The Greek saga: Competing explanations of the Greek crisis’, Kingston University London Economics Discussion Paper Series 2015-1.

- 15. Main groups of explanation Mainstream Greek disease Heterodox Marxist Non-OCA & rectifiable Non-OCA & non-rectifiable Financial expropriation Class struggle & financialisation Minskian disinflation Underconsumption & financialisation TRPF & underconsumption TRPF TRPF & imperialist exploitation

- 16. Global crisis Causes of crisis Analytical focus Profit Rate Optimal Currency Area (OCA) Twin Deficits Hypothesis (TDH) Mainstream No, external impact Policy errors, some Greek structural problems Exchange relations no yes yes Heterodox Mixed answers Weak structural problems (neoliberal policies) Monetary relations no yes no, FD vs CAD Marxist Yes, internal dimension ‘deep’ structural problems (systemic crises) Productive relations yes disproportionality no, twin deficits are results

- 17. Type of explanation CONJECTURAL [emphasis on policy errors (national or supranational)] STRUCTURAL [emphasis on the structure of the economy] Mainstream explanations WEAK STRUCTURAL [emphasis on mid-term features (neoliberalism, EMU)] STRONG STRUCTURAL [emphasis on long-term systemic features] Radical explanations Marxist explanations

- 18. MAINSTREAM EXPLANATIONS ▪3 versions: 1) a special Greek historical accident (Greek ‘disease’) (EC(2010), (2012), Gibson, Hall & Tavlas (2012), greekeconomistsforreform.com (Azariadis (2010), Dellas (2011), Ioannides (2012), Meghir, Vayanos & Vettas (2010)) 2) the Greek ‘disease’ exacerbated by EMU’s unrectifiable structural deficiencies (not-OCA) (Feldstein (2010), Krugman (2012)) 3) a ‘middle-of-the-road’ blend: the Greek disease and EMU’s deficiencies are rectifiable (De Grauwe (2010), Lane (2012), Botta (2012 ))

- 19. RADICAL EXPLANATIONS ▪4 versions: 1) Inequalities, latent undeconsumption and financialisation (Tsakalotos & Laskos (2013), Varoufakis (2012)) 2) Disinflation and financialisation a-la-Minsky (Argitis (2013)) 3) Class struggle and financialisation (Milios & Sotiropoulos (2013)) 4) Financial expropriation (Lapavitsas (2012))

- 20. MARXIST EXPLANATIONS ▪3 versions: 1) TRPF (Maniatis & Passas (2015)) 2) TRPF and imperialist exploitation (Mavroudeas & Paitaridis (2015)) 3) TRPF and underconsumption (Androulakis, Economakis & Markaki (2015)) ‘GREEK CAPITALISM IN CRISIS: MARXIST ANALYSES Edited by Stavros Mavroudeas, Routledge 2015

- 21. Mainstream explanations: A Critique • Mainstream explanations of the Greek crisis evolved from monistic to a more eclectic mix. The more articulate discern two sets of causes: (a) internal causes: exorbitant public expenditure, weak tax collecting mechanism, corruption and clientelism (even cronyism), over-regulated labor and product markets, high wages, non-market friendly institutional environment, deteriorating competitiveness etc. (b) external causes: EMU’s deficiencies, repercussions of the 2007-8 crisis • Behind this eclecticism hide versions (or combinations) of the three previously delineated explanations. • The analytical backbone of the mainstream explanations is the TDH: FD → CAD ▪ They consider the Greek case as simply a debt crisis

- 22. • Augmented version: exorbitant wage increases (ULC) ↑FD (public sector) ↑ trade deficit (private sector) ↑ CAD ▪ Keynesian argument (vs N-C Ricardian Equivalence). Mainstreamers surpassed this, with some grudges ▪ Greek TDH empirical studies do not verify it or at least offer mixed and inconclusive results: Vamvoukas (1997) confirms vs Katrakilidis & Trachanas (2011), Nikiforos et al. (2013): confirm for the pre-accession to the EMU period (1960-80), reject for the post-accession period (1981-2007), where the opposite holds (trade, and thus current account, deficit has caused increasing FD).

- 23. • Wages are posited as the cause for both FD and CAD. • They could be other analytical choices: FD can be rightfully attributed to upper- class’ notorious tax evasion (↓ public revenues) and cronyism (↑public expenditure). Mainstreamers, for obvious reasons to the supposedly high wages causation. • Well-established critiques of this argument: (1) (nominal) ULC is a non-convincing measure of competitiveness. (2) Kaldor paradox: competitiveness depends not only on costs competitiveness but also on qualitative factors (structural competitiveness). (3) ‘Race to the bottom’: A decrease in wages aiming to restore competitiveness presupposes that rival economies will maintain their wages stable or, at least, will reduce them less.

- 24. (4) Greek wages have been constantly lagging behind productivity (which increased faster than that of Germany). Thus, real ULC (i.e. the wage share) have been falling continuously for several decades.

- 25. • Mainstreamers’ wider problems: (a) Totally underestimate the role of the 2007-8 capitalist crisis (unanimously considered as a mere financial crisis without origins and causes in the sphere of real accumulation). However, if this crisis is so significant and lengthy as it appears to be, it must surely have some basis in the sphere of production. (b) Consider the Greek crisis as independent of the 2007-8 crisis. The 2007-8 crisis has only an exogenous impact on the Greek economy by worsening the international economic environment and setting off pessimist expectations about sovereign debts. (c) Fail to appreciate the fundamental structural dimensions of the problem and relegate it either to policy errors and/or to weak structural origins.

- 26. Failure to appreciate the fundamental structural dimensions o 1st perspective: considers the Greek case as a national specificity created by bad policies o 2nd perspective: recognizes a weak structural cause concerning the sphere of circulation (i.e. how the common currency is related to diverse national economies o 3rd perspective: also attributes the structural problems to the sphere of circulation (with the additional argument that, contrary to the second perspective, these problems can be surpassed) and neglects the sphere of production ➢ Only after the continuous failures of the Greek Economic Adjustment Programmes (EAPs) there was a belated and latent talk about the failure of Greece’s productive model

- 27. RADICAL EXPLANATIONS • Main features: a) Emphasize the crisis-prone nature of capitalism, thus focusing on its world structure and the 2007-8 crisis b) Critical of neoliberalism c) Criticize EMU’s neoliberal architecture and argue either for its dissolution or for its radical overhauling d) Shy of recognizing systemic deficiencies of the capitalist system; although several of them do mention them but in a rather implicit of disguised manner. They do not think that the immediate problem is capitalism as such but rather its forms of management. e) In their policy proposals they either adhere to the current productive structure (with a boost in internal demand) or erroneously think that it can be altered by simply leaving the EMU (but not the Common Market)

- 28. • The more popular Radical explanations are based on the ‘financialization’ thesis. • Other versions exist: e.g. as a fiscal crisis caused by the tax-evading and crony nature of Greek capitalists and/or adding the EMU trade imbalances (3rd variant of mainstream explanations). • The more traditional underconsumptionist explanations of crises (either of the Marxist Monthly Review (MR) or the Keynesian variant) are not popular as they do not fit to empirical data (the period preceding the crisis’ onset was characterized by a spectacular growth of consumption). In the end they usually add a ‘financialisation’ aspect. • financialization’: a problematic theory ➢ Capitalism returns to pre-capitalist forms (expropriation, unequal exchange) ➢ Interest is not part of surplus-value but independently derived ➢ Money capital is autonomised from and dominates ‘productive’ capital ➢ The 2007-8 crisis is not an a-la-Marx crisis but a financial crisis (see Mavroudeas S. & Papadatos F. (2018), ‘Is the Financialisation Hypothesis a theoretical blind alley?’, World Review of Political Economy vol.9 no.4.)

- 29. • 3 ‘financialization’ explanations of the Greek crisis: 1) Minskian inflation-disinflation, e.g. Argitis 2) ‘financialization’ in the context of the North – South divide (imbalances that caused the Greek crisis stem from the EMU), e.g. Lapavitsas. 3) ‘financialization’ in the national context; the North - South divide is an erroneous dependency argument, e.g. Milios & Sotiropoulos. • Empirical problems of the ‘financialisation’ thesis: Its main conduits (or channels) are very weak and short-lived in Greece:

- 30. ❑1st problem: Greek relatively low household debt New phenomenon (from 2004 and onwards) Lower than in most western economies The crisis ended it (banks do not offer private loans, households cannot pay)

- 31. ❑2nd problem: Greek is a bank-based capitalism, no shadow banking, limited financial leverage

- 32. MARXIST EXPLANATIONS ▪ 3 versions: 1) TRPF (Maniatis & Passas (2015)): the 1973 crisis (profitability crisis) led to a period of ‘silent depression’/ financialisation artificially prolonged it/ overaccumulation reappeared in 2007-8 as PR started falling again and the crisis erupted/ productive-unproductive labour 2) TRPF and imperialist exploitation (Mavroudeas & Paitaridis (2015)): similar plus imperialist exploitation by the euro-core countries (‘broad’ unequal exchange because of the difference in OCC)/ productive-unproductive labour 3) TRPF and underconsumption (Androulakis, Economakis & Markaki (2015)): falling profitability and underconsumption alternate as causes of crisis/ in any case either OCC or underconsumption affect PR (which is the crucial variable)/ no productive-unproductive labour distinction

- 33. Merits of Marxist explanations ▪A l-r perspective (mainstream studies usually do not consider it) ▪Data fit better in this analytical framework ▪Recognise better the deep structural dimensions whereas (a) Mainstreamers bypass them and (b) Radicals stay half-way in recognising them ▪Even Mainstream explanations have silently recognised the structural dimension by emphasising the significance of structural reforms for the success of the troika’s Economic Adjustment Programme

- 34. Mavroudeas & Paitaridis: A MARXIST STRUCTURAL EXPLANATION • A strong structural explanation of the Greek crisis: the fundamental causes in the sphere of production. • 2 structural components: (a) ‘internal’: the 2007-8 economic crisis is an a-la-Marx crisis (tendency of the profit rate to fall) which rocked the Greek economy (and the other developed ecconomies), (b) ‘external’: imperialist exploitation (i.e. ‘broad’ unequal exchange) within the EU (between North and South) worsened the position of Greece and aggravated the crisis

- 35. Figure 1. Surplus value, net operating surplus, and unproductive activities 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 1960 1963 1966 1969 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 Surplus Value Net Operating Surplus UnproductiveActivities A constant rise on the unproductive activities which are estimated as the difference between surplus value and net operating surplus (net profits).

- 36. Figure 2. Productivity and Wage 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 1960 1963 1966 1969 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 Productivity Real Wage A vigorous increase in productivity for the period 1960 - 1973. After 1973, the growth of productivity slows down whilst during the decade of 1980s it remains stagnant. In the beginning of the 1990s productivity rises again till the middle of 2000s when it starts to decline bearing similarities with the 1970s’. The real wage for the whole period it follows productivity but it never gets higher.

- 37. Figure 3. The rate of surplus value 1 1,2 1,4 1,6 1,8 2 2,2 2,4 1960 1963 1966 1969 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 Rate of Surplus Value An increase in the rate of s-v during the period 1960 - 2009 which is characterized by ups and downs. During the 1960s it increases. At the beginning of 1970s till the early 1980s declines and then it increases again. Finally, at the middle of the 2000s, it and then it sharply drops indicating capitalists’inability to extract more s-v under the given socio-political conditions.

- 38. Figure 4. The value composition of capital 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1960 1963 1966 1969 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 Composition of Capital Figure 4 depicts the evolution of the value composition of capital (C/V) as this is captured by the ratio of gross fixed capital stock (C) to variable capital (V). It steadily increases for almost the whole period. But at the beginning of the 2000s it stagnates; which can possibly be attributed to the ‘deindustrialization’ of the Greek economy with the massive escape of Greek manufacturing enterprises to the East and the increased penetration of EU imports.

- 39. Figure 5. The general PR 0,15 0,2 0,25 0,3 0,35 0,4 0,45 0,5 General PR Figure 5 depicts the evolution of the general PR and from its trajectory we can discriminate three phases before the onset of current crisis. The first one is the period 1960 - 1973 where the general PR is at a high level though with a small decline. The second one is the period of crisis (1973 - 1985) when the general PR falls dramatically. The third period is that of capitalist restructurings (1985 – 2009) when the general PR displays a slight recover and then remains stagnant.

- 40. III. Structural reforms and the issue of the productive model in the Greek crisis • Greece and European Integration: a failed productive model ➢ After the 2nd WW and the Civil War, Greek capitalism – under the auspices of the West and primarily the US – was structurally transformed: ❑ A limited but vibrant industrialization: around mainly light industry, e.g; textiles, food processing; a few exceptions, e.g. oil industry; its dominant fraction (maritime capital) is a case of its own [with the one foot inside and the other outside the country) – The secondary sector became the bigger sector of the Greek economy ❑ A strongly protected economy (capital controls, trade protectionism, competitive devaluations etc.) ❑ It was based on low wages (anti-communist state) and limited welfare system ➢ This productive model was quite coherent (strong inter-branch linkages) It enjoyed a 25 years’ ‘golden age’ (approximately 1950-1975)

- 41. ➢ The 1974-5 global crisis and the fall of the military dictatorship (1974) injured gravely this configuration: ❑ Resurgence of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall (TRPF) due to increased organic composition of capital (OCC) ❑ Inability to restrain long-repressed wages ➢ Their combined result: an acceleration of the TRPF ➢ Greek capital had already before the dictatorship decided to enter the European Integration (then under the US auspices in order to contain the Eastern bloc) ➢ With the eruption of the crisis and the post-dictatorship popular radicalism Greek capital proceeded more vigorously in the path of European Integration in order to: ❑ Contain popular radicalism (thus weakening in the long-run wage increases demands) ❑ Transform itself through its partnership with the more developed West European capitals towards a more profitable and competitive productive model

- 42. ➢This new ‘Big Idea’ (an infamous in Greece term) had short-term positive (for Greek capital) results but also long-term disastrous consequences ❑Popular radicalism was contained ❑In the 1990s – with the collapse of the Eastern Bloc – Greek capital enjoyed a boost in its profitability through its (economic) imperialist expansion in the Balkans but in the face of competition from the more developed West European capitals the coherence of its productive model was disrupted: ❑ Deindustrialization ❑ Further curtailment of the primary sector ❑ Ballooning of the services sector as the Greek capital retreated there in order to enjoy covert protectionism (crony relations with the state, family capitalism etc.) ❑ Worsening of the trade and current account balance: a small open economy depending upon the Western Europe mainly (Economakis G. & Markaki M. & Anastasiadis A. (2015), Structural Analysis of the Greek Economy, RRPE Volume 47, Issue 3)

- 43. ➢ These constitute the structural basis of the current Greek crisis: they depressed in the long-run capital profitability

- 44. Sectoral Structure of Greek GDP (INE-GSEE)

- 45. R&D Very low R&D (OECD)

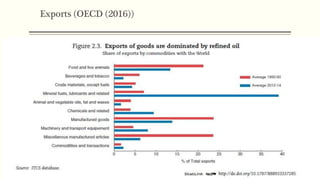

- 46. External Trade ▪ Oil products represent the 40% of both imports and exports

- 48. ▪Trade Balance -14 -12 -10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 1960 1963 1966 1969 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017 Net Exports (% GDP) source: AMECO

- 49. Troika’s Economic Adjustment Programmes and the issue of the failed productive model ▪ The guilty silence about the failure of the current Greek productive model: a product of the country’s participation in the European integration ▪ A conjunctural understanding of the Greek crisis in order to hide its systemic origins ▪ A belated recognition of a limited structural nature: institutional failure (to implement the EAPs and the ‘last soviet economy’ stupidity) ▪ A clumsy industrial policy: simply revamp the existing failed productive model

- 50. The Greek EAPs: a problematic modification of IMF’s SAPs ❑Longer (4 years+): out of necessity because of systematic failures ❑More front-loaded (at the insistence of EU (technically because of EU treaties clauses [Maastricht, SGP, 6-pack], politically because EU wanted more urgently than IMF a solution in order to avoid expansion of the problems to the whole EMU) ❑No initial debt restructuring (because both the IMF and the EU feared a global contagion) ❑No exchange rate devaluation mechanism (as Greece belongs to the EMU) ❑No tailor-made (accommodative) monetary policy (as dictated by the ‘expansionary austerity doctrine’ because it is set by the ECB) ❑EAPs’ loans finance only the FD and bank recapitalization (whereas traditional IMF programmes financed the whole CAD, Pissani-Ferry et al (2013), because no classical b-o-p crisis was considered possible in the EMU) ❑Dual conditionality (IMF and EU): each institution proceeds according to its own separate standards

- 51. ➢ The backbone of the EAPs is the sustainability of debt (DSA) as it is their immediate and more pressing problem (fear of contagion to the rest of the EZ and the world, initial lack of a EU mechanism (hastily designed EFSF and later ESM)). ➢ The structural reforms play second fiddle as a supportive mechanism. It was elevated after the failures of the first two EAPs as a deus-ex-machina. However, it is a very problematic (see political economic problems) and long-run mechanism. ➢ The estimations about a ‘growth dividend’ coming from structural reforms fail systematically because of analytical and empirical errors. ➢ Only belatedly there was an incoherent talk about a new productive model and some form of industrial policy ➢ EAPs’ vision of a new productive model: a renovation of the already existing one (dictated by the European Integration) ➢ Industrial policy: weak, horizontal, following the market and around ‘hand-outs’ (NSRF, infamous ‘development laws’)

- 52. ▪ EAPs’ vision of a new productive model ➢ Greece in the periphery of European transnational value chains: a model of externally depended and oriented economy ➢ An export-led growth (typical of IMF’s prescriptions) that fails to materialize: mainly oil products and tourism, some small and isolated niches ➢ It depends upon low wages ➢ This is an anti-labour strategy with serious analytical and empirical problems: ❑ Kaldor’s paradox ❑ emphasis on wage cost competitiveness ❑ neglect of other elements of cost competitiveness (profit margins) ❑ neglect of qualitative issues (type of products, added value, techological expertise etc.)

- 53. ➢ In practice it has already failed: ❑ the improvement of the trade balance was caused by the drastic reduction of imports ❑ Exports remain extremely volatile and dependent upon ‘one off’ deals ❑ Even a small increase in GDP requires an increase of imports (intermediate inputs) ❑ Attempts to diversify trade beyond the EU are weak and unstable ➢ This failed productive model vision is followed by all establishment parties (SYRIZA, ND, KINAL etc.) with cosmetic changes

- 54. ▪ EAPs’ industrial policy ➢ Weak: not challenging but reproducing the existing failed productive model ➢ Horizontal: facilitating entrepreneurship in general (relax of regulations, easiness to open [and close] businesses, bankruptcy laws etc.) ➢ Following the market: depending upon private investment ➢ Expecting FDIs: fail to materialize; only ‘fire sales’ ➢ Since the Programme of Public Investment is almost defunct (the more easily and systematically curtailed part of the fiscal budget), industrial policy depends upon EU funds ➢ around ‘hand-outs’ (NSRF, infamous ‘development laws’): capital’s long- term abstention from investment (the gross fixed capital formation ratio is almost a straight line at very low levels comparing to the past). In order to slightly ameliorate it packages of ‘hand-outs’ are organized: ❑ ‘Development laws’ and strategic development framework ❑ National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF)

- 55. Greece: Gross Fixed Capital formation (% GDP)

- 56. ▪ ‘Development laws’ and strategic development framework ➢ ‘development laws’: a misnomer. Subsidies and tax allowances mainly ‘eaten’ by the tourist industry. Notorious for failing to boost employment. ➢ Strategic development framework: non-existent. Usually political declarations for electoral purposes. Nothing substantial, e.g. ND: turning Greece to an EU logistics center (utterly stupid given its geographical location, transportation infrastructure and the situation in the Balkans)/ SYRIZA: smart specialization (old and defunct idea) ➢ No aspiration of an industrial rejuvenation

- 57. ▪ The NRSF: ‘blood money’ ➢the only beefy part: EU funds ➢The much-tooted and practically irrelevant Juncker plan: hence, the amount of funds cannot fill the productive gap (that is the capital needed in order to return to the pre-crisis GDP level) ➢However, the only money around ➢It reproduces the existing division of labour (failed productive model) ➢ NSRF 2014-20 (https://www.espa.gr/el/pages/staticESPA2014-2020.aspx ), 8 priority sectors: 1) Agro-nutrition 2) Health - medicines 3) Information and communication technologies 4) Energy 5) Environment and sustainable development 6) Transport 7) Materials - constructions 8) Tourism, culture, creative industries

- 58. ➢NSRF’s priorities are the product of lobbying by the Greek capitalists which has been accepted and institutionalized by the EU, as it conforms with the latter’s objectives ➢The NSRF origin is in two previous studies: IOBE (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research – the think tank of the Greek capitalists) and McKinsey (McKinsey (2012), ‘Greece 10 Years Ahead: Defining Greece's new growth model and strategy) ➢This is freely admitted: ‘According to Development Minister of the previous governent Kostis Hatzidakis, the new NSRF (2014-2020) focuses on 8 priority sectors, where the country has comparative advantages, according to the proposals of Mc Kinsey and IOBE.’ ➢The NSRF (2014-2020) covers both the previous ND-PASOK and the current SYRIZA administration. Tellingly, in an area which is supposed to be guided according to national government prerogatives there is not even the slightest change. The priority sectors remain the same. The only cosmetic change made by

- 59. In place of conclusions ▪ Mainstream economics have a weak understanding of structural change. This stems from: ➢A problematic analytical framework: economics of circulation ➢Their class perspective: reproduction of the social system ▪ Even in cases of blatant failure, they cannot think out of the box ▪ Heterodox economics act as the ‘bad doctor’ of the system: despised because he suggests painful solutions but necessary in times of acute danger. However, because they also shy away from touching the foundations of the system they also fail in grave situations. ▪ Marxist Political Economy offers a superior analytical framework. However, it is oficially rejected as it is intrinsically linked to the overturn of the capitalist system.

![From the structural change of developmentalism to the structural reforms of the

Washington Consensus

▪ Its high time: after the 2nd WW and till the 1973 global capitalist crisis

➢ A stellar example: Latin American Structuralism (and ISI [Import

Substituting Industrialisation]) and broadly speaking Developmentalism (also

in the East Asia)

➢ Its dominant conception: change in the production structure through activist

and discrete state policies

➢ Industrial policy: a crucial component of these state policies. Industrial policy

was conceived as a heavy toolbox of vertical measures with strong

asymmetrical impact on different sectors and branches of the economy

▪ Activist theories and policies of structural change stall after the 1973 global

crisis:

➢ Preoccupation mainly with inflation and stabilization rather than growth

➢ The long march of developing economies halted](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conceptsofstructuralchange-computensemadrid2019-190424151037/85/Concepts-of-structural-change-Lecture-Universidad-Computense-Madrid-2019-4-320.jpg)

![Type of explanation

CONJECTURAL

[emphasis on policy errors

(national or supranational)]

STRUCTURAL

[emphasis on the structure of

the economy]

Mainstream

explanations

WEAK

STRUCTURAL

[emphasis on mid-term

features (neoliberalism,

EMU)]

STRONG

STRUCTURAL

[emphasis on long-term

systemic features]

Radical

explanations

Marxist

explanations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conceptsofstructuralchange-computensemadrid2019-190424151037/85/Concepts-of-structural-change-Lecture-Universidad-Computense-Madrid-2019-17-320.jpg)

![The Greek EAPs: a problematic modification of IMF’s SAPs

❑Longer (4 years+): out of necessity because of systematic failures

❑More front-loaded (at the insistence of EU (technically because of EU treaties

clauses [Maastricht, SGP, 6-pack], politically because EU wanted more urgently

than IMF a solution in order to avoid expansion of the problems to the whole EMU)

❑No initial debt restructuring (because both the IMF and the EU feared a global

contagion)

❑No exchange rate devaluation mechanism (as Greece belongs to the EMU)

❑No tailor-made (accommodative) monetary policy (as dictated by the

‘expansionary austerity doctrine’ because it is set by the ECB)

❑EAPs’ loans finance only the FD and bank recapitalization (whereas traditional

IMF programmes financed the whole CAD, Pissani-Ferry et al (2013), because no

classical b-o-p crisis was considered possible in the EMU)

❑Dual conditionality (IMF and EU): each institution proceeds according to its own

separate standards](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conceptsofstructuralchange-computensemadrid2019-190424151037/85/Concepts-of-structural-change-Lecture-Universidad-Computense-Madrid-2019-50-320.jpg)

![▪ EAPs’ industrial policy

➢ Weak: not challenging but reproducing the existing failed productive model

➢ Horizontal: facilitating entrepreneurship in general (relax of regulations,

easiness to open [and close] businesses, bankruptcy laws etc.)

➢ Following the market: depending upon private investment

➢ Expecting FDIs: fail to materialize; only ‘fire sales’

➢ Since the Programme of Public Investment is almost defunct (the more easily

and systematically curtailed part of the fiscal budget), industrial policy

depends upon EU funds

➢ around ‘hand-outs’ (NSRF, infamous ‘development laws’): capital’s long-

term abstention from investment (the gross fixed capital formation ratio is

almost a straight line at very low levels comparing to the past). In order to

slightly ameliorate it packages of ‘hand-outs’ are organized:

❑ ‘Development laws’ and strategic development framework

❑ National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conceptsofstructuralchange-computensemadrid2019-190424151037/85/Concepts-of-structural-change-Lecture-Universidad-Computense-Madrid-2019-54-320.jpg)