Understanding English Grammar 9th Edition (learnenglishteam.com).pdf

- 1. N I N T H E D I T I O N Understanding English Gram m ar Martha Kolln Robert Funk

- 2. English Grammar N I N T H E D I T I O N Martha Kolln The Pennsylvania State University Robert Funk Eastern Illinois University PEARSON Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montreal Toronto Delhi Mexico City Sao Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo

- 3. Senior Sponsoring Editor: Katharine Glynn Assistant Editor: Rebecca Gilpin Senior Marketing Manager: Sandra McGuire Senior Supplements Editor: Donna Campion Production Manager: Denise Phillip Project Coordination, Text Design, and Electronic Page Makeup: S4Carlisle Cover Designer/Manager: Wendy Ann Fredericks Cover Photo: © iStockphoto Senior Manufacturing Buyer: Roy Pickering Printer/Binder: Courier Corporation / Westford Cover Printer: Courier Corporation / Westford Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kolln, Martha. Understanding English grammar / Martha Kolln, Robert Funk.— 9th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Previous ed.: 2009. ISBN-13: 978-0-205-20952-1 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-205-20952-1 (alk. paper) 1. English language— Grammar. I. Funk, Robert. II. Title. PEI 112.K64 2011 428.2— dc23 2011028417 Copyright © 2012, 2009, 2006 by Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. M anufactured in the U nited States of America. This p u b lication is protected by Copyright, and permission should be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or likewise. To obtain permission(s) to use material from this work, please submit a written request to Pearson Education, Inc., Permissions Department, One Lake Street, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458, or you may fax your request to 201-236-3290. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 — V013— 14 13 12 PEARSON ISBN 10: 0-205-20952-1 www.pearsonhighered.com ISBN 13: 978-0-205-20952-1

- 4. Contents Preface xvii PART I Introduction 1 C h a p t e r 1 The Study o f Grammar: An Overview 3 English: A World Language 3 Three Definitions of Grammar 4 Traditional School Grammar 5 Modern Linguistics 6 Structural Grammar 6 Transformational Grammar 7 The Issue of Correctness 8 Language Variety 10 Language Change 11 Language in the Classroom 12 Key Terms 13 Further Reading 13 p a r t T i The Grammar o fBasic Sentences 15 C h a p t e r 2 Words and Phrases 16 Chapter Preview 16

- 5. Contents The Form Classes 16 Nouns and Verbs 17 The Noun Phrase 18 The Verb Phrase 19 NP + VP = S 20 Adjectives and Adverbs 22 Prepositional Phrases 24 The Structure Classes 26 Key T erms 27 C h a p t e r 3 Sentence Patterns 28 Chapter Preview 28 Subjects and Predicates 29 The Sentence Slots 30 The Be Patterns 32 The Linking Verb Patterns 35 The Optional Slots 37 The Intransitive Verb Pattern 38 Exceptions to the Intransitive Pattern 39 Intransitive Phrasal Verbs 40 The Transitive Verb Patterns 42 Transitive Phrasal Verbs 43 The Indirect Object Pattern 44 The Object Complement Patterns 47 Compound Structures 49 Exceptions to the Ten Sentence Patterns 51 Sentence Types 51 Interrogative Sentences (Questions) 52 Imperative Sentences (Commands) 53 Exclamatory Sentences 54 Punctuation and the Sentence Patterns 54 Diagramming the Sentence Patterns 55 Notes on the Diagrams 56 The Main Line 56 The Noun Phrase 56 The Verb Phrase 57 The Prepositional Phrase 58

- 6. Contents Compound Structures 58 Punctuation 58 Key Terms 59 Sentences for Practice 59 Questions for Discussion 60 Classroom Applications 62 C h a p t e r 4 Expanding the Main Verb 63 Chapter Preview 63 The Five Verb Forms 63 The Irregular Be 65 Auxiliary-Verb Combinations 66 The Modal Auxiliaries 70 The “Future Tense” 72 The Subjunctive Mood 73 Tense and Aspect 74 Using the Verb Forms 75 Exceptions to the Verb-Expansion Rule 76 The Stand-In Auxiliary Do 17 The Verb System of African American Vernacular English 80 Key Terms 82 Sentences for Practice 82 Questions for Discussion 83 Classroom Application 84 C h a p t e r 5 Changing Sentence Focus 86 Chapter Preview 86 The Passive Voice 86 The Passive Get 89 The Transitive-Passive Relationship 90 Patterns VIII to X in Passive Voice 90 Changing Passive Voice to Active 92 The Passive Voice in Prose 93 Other Passive Purposes 94 The There Transformation 95 Cleft Sentences 98

- 7. x Contents Key Terms 100 Sentences for Practice 101 Questions for Discussion 102 Classroom Applications 103 PART III Expanding the Sentence 105 Form and Function 105 C h a p t e r 6 Modifiers of the Verb: Adverbials 108 Chapter Preview 108 The Movable Adverbials 109 Adverbs 109 Prepositional Phrases 112 Nouns and Noun Phrases 114 Verb Phrases 117 Dangling Infinitives 119 Participles as Adverbials 121 Clauses 121 Punctuation of Adverbials 123 Key Terms 125 Sentences for Practice 126 Questions for Discussion 126 Classroom Application 127 C h a p t e r 7 Modifiers o fthe Noun: Adjectivals 128 Chapter Preview 128 The Determiner 130 Adjectives and Nouns 131 Prenoun Participles 133 Prepositional Phrases 136 Relative Clauses 138 Participial Phrases 143 Passive Participles 146 Movable Participles 147 The Participle as Object Complement 148 Participles as Adverbials or Adjectivals 151

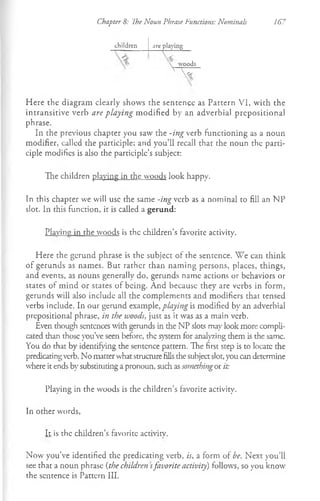

- 8. Contents Punctuation of Clauses and Participles 151 Multiple Modifiers 155 Other Postnoun Modifiers 156 Infinitives 156 Noun Phrases 157 Adjectives 157 Adverbs 158 Key Terms 159 Sentences for Practice 159 Questions for Discussion 160 Classroom Applications 162 C h a p t e r 8 The Noun Phrase Functions: Nominals 163 Chapter Preview 163 The Nominal Slots 164 Appositives 164 Punctuation of Appositives 165 Noun Phrase Substitutes 166 Gerunds 166 The Pattern of the Gerund 169 The Subject of the Gerund 171 Dangling Gerunds 171 Infinitives 173 The Subject of the Infinitive 175 Nominal Clauses 177 The Expletive That 178 Interrogatives 180 Yes/No Interrogatives 182 Punctuation of Nominal Clauses 183 Nominals as Delayed Subjects 184 Key Terms 185 Sentences for Practice 185 Questions for Discussion 186 Classroom Applications 187 C h a p t e r 9 Sentence Modifiers 189 Chapter Preview 189

- 9. xii Contents Nouns of Direct Address: The Vocatives 193 Interjections 194 Subordinate Clauses 195 Punctuation of Subordinate Clauses 196 Elliptical Clauses 197 Absolute Phrases 199 Appositives 202 Relative Clauses 203 Key Terms 204 Sentences for Practice 205 Questions for Discussion 205 Classroom Applications 207 C h a p t e r 1 0 Coordination 209 Chapter Preview 209 Coordination Within the Sentence 209 Punctuation 209 Elliptical Coordinate Structures 212 Subject-Verb Agreement 213 Parallel Structure 215 Coordinating Complete Sentences 216 Conjunctions 216 Semicolons 218 Colons 219 Diagramming the Compound Sentence Key T erms 221 Sentences for Practice 221 Questions for Discussion 222 Classroom Applications 223 PART IV Words and Word Classes 225 C h a p t e r 1 1 Morphemes 227 Chapter Preview 227 Bases and Affixes 229 Bound and Free Morphemes 229

- 10. Contents xiii Derivational and Inflectional Morphemes 230 Allomorphs 233 Homonyms 234 Compound Words 235 Key Terms 236 Questions for Discussion 236 Classroom Applications 238 C h a p t e r 12 The Form Classes 239 Chapter Preview 239 Nouns 239 Noun Derivational Suffixes 240 Noun Inflectional Suffixes 241 The Meaning of the Possessive Case 244 Irregular Plural Inflections 245 Plural-Only Forms 246 Collective Nouns 246 Semantic Features of Nouns 247 Verbs 250 Verb Derivational Affixes 250 Verb Inflectional Suffixes 251 Adjectives 252 Adjective Derivational Suffixes 252 Adjective Inflectional Suffixes 253 Subclasses of Adjectives 255 Adverbs 257 Adverb Derivational Suffixes 257 Adverb Inflectional Suffixes 259 Key Terms 260 Questions for Discussion 261 Classroom Applications 263 C h a p t e r 13 The Structure Classes 265 Chapter Preview 265 Determiners 265 The Expanded Determiner 269 Auxiliaries 270 Qualifiers 272

- 11. xiv Contents Prepositions 274 Simple Prepositions 274 Phrasal Prepositions 276 Conjunctions 278 Coordinating Conjunctions 278 Correlative Conjunctions 279 Conjunctive Adverbs (Adverbial Conjunctions) 280 Subordinating Conjunctions 280 Interrogatives 282 Expletives 282 There 283 That 283 Or 283 As 283 I f and Whether (or Not) 284 Particles 284 Key Terms 285 Questions for Discussion 286 Classroom Applications 287 C h a p t e r 1 4 Pronouns 289 Chapter Preview 289 Personal Pronouns 290 Case 290 The Missing Pronoun 292 Reflexive Pronouns 295 Intensive Pronouns 296 Reciprocal Pronouns 297 Demonstrative Pronouns 297 Relative Pronouns 298 Interrogative Pronouns 299 Indefinite Pronouns 300 Key Terms 303 Questions for Discussion 303 Classroom Applications 305

- 12. Contents xv P A R T V Grammarfor Writers 307__ C h a p t e r 15 Rhetorical Grammar 309 Chapter Preview 309 Sentence Patterns 310 Basic Sentences 310 Cohesion 311 Sentence Rhythm 312 End Focus 313 Focusing T ools 315 Choosing Verbs 316 The Overuse of Be 318 The Linking Be and Metaphor 319 The Passive Voice 320 The Abstract Subject 321 Who Is Doing What? 321 The Shifting Adverbials 322 The Adverbial Clause 323 The Adverbs of Emphasis 326 The Common Only 326 Metadiscourse 327 Style 329 Word Order Variation 330 Ellipsis 331 The Coordinate Series 331 The Introductory Appositive Series 332 The Deliberate Sentence Fragment 332 Repetition 333 Antithesis 335 Using Gender Appropriately 336 Key Terms 339 C h a p t e r 16 Purposeful Punctuation 340 Chapter Preview 340 Making Connections 341

- 13. xvi Contents Compounding Sentences 341 Compounding Structures Within Sentences 342 Connecting More Than Two Parts: The Series 343 Separating Prenoun Modifiers 343 Identifying Essential and Nonessential Structures 344 Signaling Sentence Openers 345 Signaling Emphasis 345 Using Apostrophes for Contraction and Possessive Case 346 PART VI Glossary of Grammatical Terms 349 Appendix: Sentence Diagramming 366 Answers to the Exercises 371 Index 420 /

- 14. Preface The central purpose of this ninth edition of UnderstandingEnglish Grammar remains the same as it has always been: to help students understand the sys tematic nature of language and to appreciate their own language expertise. We recognize that most people who use this book are speakers of Eng lish who already know English grammar, intuitively and unconsciously. But wc also realize that many of them don' t understand what they know: They’re unable to describe what they do when they string words together, and they don’t know what has happened when they encounter or produce unclear, imprecise, or ineffective speech and writing. Their grammatical ability is extraordinary, but knowing how to control and improve it is a conscious process that requires analysis and study. In recent years, the widespread institution of state-mandated standards, the growth of high-stakes testing, and the increased use of diagnostic writ ing samples make it clear that today’s students— and those who arc pre paring to teach them— must both know and understand grammar. Although Understanding English Grammar assumes no prior knowl edge on the readers’part beyond, perhaps, vague recollections of long-ago grammar lessons, we do assume that, as language users, students will learn to draw on their subconscious linguistic knowledge as they learn about the structure of English in a conscious way. Wc help students tap into their subconscious grammar knowledge with a chapter on words and phrases, laying the groundwork for the study of sentence patterns and their expansion. Our focus on syntax begins where the students’ own language strengths lie: in their sentence-producing abil ity. W ith a few helpful guidelines, the basic sentence patterns become familiar very quickly and provide a framework for further grammatical and rhetorical investigations. English language learners (ELLs) too will appreciate the detailed step-by-step approach, along with highlighted discussions of ELL issues. The thorough study of sentence patterns in Chapter 3 builds the foundation for the rest of the chapters. The study of grammar, of course, is not just for English majors or for future teachers: It is for people in business and industry, in science and engineering, in law and politics, in the arts and social services. Every user of the language, in fact, will benefit from the consciousness-raising that xvii

- 15. results from the study of grammar. The more that speakers and writers know consciously about their language, the more power they have over it and the better they can make it serve their needs. Teachers familiar with the previous editions of Understanding English Grammar will find the same progression of topics in this new one: Part I: The Study of Grammar: An Overview Part II: The Grammar of Basic Sentences Part III: Expanding the Sentence Part IV: Words and Word Classes Part V: Grammar for Writers In this revision we have tried to look at ever}7topic, every discussion through the eyes of a novice reader; we have taken to heart the ideas and opinions of our reviewers and of others, as well, who have taken the time to comment. As a result, we have made refinements, both large and small, in the discussions, exercises, and examples throughout the book. Following are the major changes you will sec: • Chapters open with a bulleted list that lays out the purposes and the goals we have set for students. Together with the chapter-ending list of key terms, this opening set of goals can provide a comprehensive guide for study and review. • In a new feature called "Usage Matters,” we explore issues of grammar, word choice, and writing conventions— and even out right myths— that can frustrate both students and teachers. You will find them listed in the “U” section of the Index. • Chapter 2 has undergone a makeover that clarifies the basics of noun phrases and verb phrases; it also includes a new summary section on the structure classes. • In three new topic-centered exercises, students will learn about the Oregon Trail, the development of printing, and the game of tennis and its star players. Many other Exercises and Questions for Discussion have also been updated with new items. • New diagrams have been added, illustrating compound structures, modifiers with hyphens, and the infinitive phrase functioning as an appositive. Ideas and suggestions from you and your students are always welcome. Exercises throughout the chapters reinforce the principles of grammar as they are introduced. Answers to the exercises, which are provided at the xviii Preface

- 16. Preface xix end of die book, give the book a strong self-instructional quality. Other exercises, called “Investigating Language,” will stimulate class discussion, calling on students to tap into their innate language ability. Chapters 3 through 14 end with a list of key terms, a section of prac tice sentences (for which answers are provided only in the Instructor’ s Manual), a series of questions for discussion that go beyond the concepts covered in the text, and several classroom applications that can be used in your collcge classcs as well as in the future classrooms of your students. The students will also find the Glossary of Grammatical Terms and the / Index extremely helpful. Supplementing the ninth edition of the text, the Instructor ’ s M an ual (ISBN 0-205-20958-0) includes analyses of the practice sentences, suggested answers for the discussion questions, and suggestions for us ing the book. The Instructor’ s Manual is available from your Pearson representative. Another supplement to the text is the new edition of Exercisesfor Un derstanding English Grammar (ISBN 0-205-20960-2), with exercises that go beyond those found in the text, many of which call for the students to compose sentences. To keep the self-instructional quality that teachers ap preciate, answers for all items are included, where answers are appropriate. However, there arc now ten additional “Test Exercises” lor which the an swers arc not provided; these can be used for testing and review. An Answer Key for these test exercises will be available online to instructors who adopt the new edition of Exercisesfor Understanding English Grammar. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Understanding English Grammar has once again been revised, corrected, and shaped by the questions and comments of students and colleagues who use the book. We are particularly grateful to the following reviewers for their thoughtful assessments of the previous edition and their recom mendations for revision: William Allegrezza, Indiana University Northwest Booker T. Anthony, Fayetteville State University James C Burbank, University of New Mexico Brian Jackson, Brigham Young University Gloria G. Jones, Winthrop University Carlana Kohn-Davis, South Carolina State University Mimi Rosenbush, University O f Illinois at Chicago

- 17. Preface Rachel V. Smydra, Oakland University Gena D. Southall, Longwood University Duangrudi Suksang, Eastern Illinois University. Finally, our special thanks goes to our editor and friend, Ginny Blanford, and her efficient Assistant Editor Rcbecca Gilpin. Martha Kolln Robert Funk

- 18. PART I Introduction T he subject of English grammar differs markedly from every other subject in the curriculum— far different from history or math or biology or technical drawing. What makes it different? If your native lan guage is English, you do. As a native speaker, you’re already an expert. You bring to the study of grammar a lifetime of “knowing” it— except for your first year or two, a lifetime of producing grammatical sentences. Modern scholars call this expertise your “language competence.” Unlike the competence you may have in other subjects, your grammar compe tence is innate. Although you weren’t born with a vocabulary (it took a year or so before you began to perform), you were born with a language potential just waiting to be triggered. By the age of two you were put ting words together into sentences, following your own system of rules: “Cookie all gone”; “Go bye-bye.” Before long, your sentences began to resemble those of adults. And by the time you started school, you were an expert in your native language. Well, almost an expert. Ihcre were still a few gaps in your system. For example, you didn’t start using verb phrases as direct objects (I like read ing books) until perhaps second grade; and not until third or fourth grade did you use although or even ifio introduce clauses (Pm going home even i f you’ re not). But for the most part, your grammar system was in place on your first day of kindergarten. At this point you may be wondering why you’re here— in this class, reading this texebook— if you’re already an expert. The answer to that question is important: You’re here to learn in a conscious way the gram mar that you use, expertly but subconsciously, every day. You’ll learn to think about language and to talk about it, to understand and sharpen your own reading and writing skills, and, if your plans for the future include teaching, to help others understand and sharpen theirs. 1

- 19. 2 Part /: Introduction For those of you whose mother congue is a language other than English, you will have che opportunity to compare the underlying structure of your first language as you add the vocabulary and structure of English grammar to your language awareness. This chapter of Part I begins by recognizing English as a world language. We then take up the ways in which it has been studied through the years, along with the issues of correctness and standards and language change. In all of these discussions, a keyword is awareness. The goal of Understanding English Grammar is to help you bccomc consciously aware of your innate language competence.

- 20. AP^ £ /? 1 The Study of Grammar: An Overview ENGLISH: A WORLD LANGUAGE All over the world every day, there are people, young and old, doing what you’re doing now: studying English. Some are college students in China and Korea and Tunisia preparing for the proficiency test required for admission to graduate school in America. Some are businesspeople in Germany and Poland learning to communicate with their European Union colleagues. Others are adults here in the United States studying for the written test that leads to citizenship. And in the fifty or more countries where English is either the first language or an official second language, great numbers of students are in elementary and secondary classrooms like those you inhabited during your K-12 years. As the authors of The Story o fEnglish make clear, English is indeed a world language: The figures tell their own story. According to the best estimates available, English is now the mother tongue of about 380 million people in traditionally English-speaking countries such as Britain, Australia and the United States. Add to this the 350 million “second- language” English speakers in countries like India, Nigeria and Singapore, and a staggering further 500 to 1000 million people in countries like China, Japan and Russia that acknowledge the importance of global English as an agent of global capitalism, and you arrive at a total of nearly 2000 million, or at least a third of the worlds population.1 1M cCrum c l al., !he Story o fEnglish* p. xviii. [Sec reference list, page l4 .| 3

- 21. 4 Pan I: Introduction For the PBS documentary series Ihe Story of English, first broadcast in 1986, Robert MacNcil traveled the world to interview native speakers of English: among them, speakers of Indian English in Delhi and Calcutta, of Scots English in the Highlands of Scotland, of Pidgin in Papua New Guinea, and of Gullah in the Sea Islands of Georgia. In many of his con versations, the language he heard included vocabulary, pronunciation, and sentence structure far removed from what we think of as mainstream English. The theme of the documentary was clear: The story of English— or Englishes— is diversity. There is no one “correct”— no one “proper”— version of the English language: There are many. Even the version we call American English has a wide variety of dialects.2 Different parts of the country, different levels of education, different ethnic backgrounds, different settlement histories— all of these factors produce differences in language communities. Modern linguists recognize that every variety of English is equally grammatical. We could cite many examples (and so could you!) of language structures that vary from one region of the country to another. There’s a word for this phe nomenon: We call these variations regionalisms. For instance, in central and western Pennsylvania you will hear “The car needs washed,” whereas in eastern Pennsylvania (and most other parts of the country') dirt}' cars “need washing” or “need to be washed.” Clearly, there is no one “exact rule” for the form that follows the verb need in this context. Another example is the well-known you all or y ’ all of southern dia lects; in both midwestern and Appalachian regions you will hearjyou 'uns or y'uns in parts of Philadelphia you will hear youse. These are all methods of pluralizing the pronoun you. It’s probably accurate to say that the majority of speech communities in this country7have no separate form foryou when it’s plural. But obviously, some do. And although they may not appear in grammar textbooks, these plurals arc part of the grammar of many regions. It will be useful, before looking further at various grammatical issues, to consider more carefully the meaning ofg>'ammar. THREE DEFINITIONS OF GRAMMAR Grammar is certainly a common word. You’ve been hearing it for most of your life, at least during most of your school life, probably from third or fourth grade on. However, there arc many different meanings, or differ ent nuances of meaning, in connection with grammar. 'Ihe three we will discuss here arc fairly broad definitions that will provide a framework for - W ords in boldfacc type arc defined in the Glossary or Grammaiical 1erms. beginning on 349-

- 22. Chapter 1: Ihe Study o f Grammar: An Overview .5 thinking about the various language issues you will be studying in these chapters: Grammar 1: The system o f rules in our heads. As you learned in the Introduction, on page 1, you bring to the study of grammar a lifetime of “knowing” how to produce sentences. This subconscious system of rules is your “language competence.” It’s important to rccognize that these inter nalized rules varyr from one language community to another, as you read in connection with the plural forms ofyou. Grammar 2: Theformal description of the rules. This definition refers to the branch of linguistic sciencc concerned with the formal description of language, the subject matter of books like this one, which identify in an objective way the form and structure, the syntax, of sentences. This is the definition that applies when you say, “I’m studying grammar this semester.” Grammar 3: Ihe social implications o f usage, sometimes called “ linguistic etiquette." This definition could be called do’s and don’t’s of usage, rather than grammar. For example, using certain words may be thought of as bad manners in particular contexts. This definition also applies when people use terms like “poor grammar” or “good grammar.” TRADITIONAL SCHOOL GRAMMAR In grammar books and grammar classes, past and present, the lessons tend to focus on parts of speech, their definitions, rules for combining them into phrases and clauses, and sentence exercises demonstrating grammati cal errors to avoid. This model, based on Latin’s eight parts of speech, goes as far back as the Middle Ages, when Latin was the language of culture and enlightenment, of literature and religion— when Latin was considered the ideal language. English vernacular, the language that people actually spoke, was considered inferior, almost primitive by comparison. So it was only natural that when scholars began to write grammars of English in the seventeenth century, they looked to Latin for their model. In 1693 the English philosopher John Locke declared that the pur pose of teaching grammar was “to teach Men not to speak, but to speak correctly and according to the exact Rules of the Tongue.” These words of Locke define the concept that today wc call prescriptive grammar.3 Grammar books have traditionally been guided by normative principles, that is, for the purpose of establishing norms, or standards, to prescribe “the exact rules of the tongue.” Much of what we call traditional grammar—sometimes called “school grammar”— is the direct descendant of those early Latin-based books. Its From Some Thoughts Concerning Education, quoted in Baron, Grammar and Good Tasie, p. 121. (See reference Use, page 13.]

- 23. 6 Pan I: Introduction purpose is to teach literacy, rhe skills of reading and writing, continuing the normative tradition. And most language arts textbooks today continue to be based on Latin’s eight parts of speech. A more modern approach to language education, however, is guided by the work of linguists, who look at the way the language is actually used. Rather than prescribing how language should be used, an accurate descriptive grammar Ascribes the way people speak in everyday situa tions. Such a description recognizes a wide variety of grammatical forms. The standard of formal written English is, of course, one of them. MODERN LINGUISTICS The twentieth century witnessed important new developments in linguis tics, the scientific study of language. One important difference from tradi tional school grammar was the emphasis on objectivity in describing the language and its word classes, together with a rejection of prescriptivism. In the 1920s a great deal of linguistic research was carried out by anthropologists studying Native American languages, many of which were in danger of being lost. It was not unusual for a few elders to be the only remaining speakers of a tribe’s language. W hen they died, the language would die with them. To understand the structure underlying languages unknown to them, researchers could not rely on their knowledge of Western languages: They could not assume that the language they were hearing was related cither to Latin or to the Germanic roots of English. Nor could they assume that word classes like adjective and pronoun and preposition were part of the sentences they were hearing. To be objective in their description, they had to start from scratch in their thinking about word categories and sentence structure. Structural Grammar. The same kind of objectivity needed to study the grammar of an unknown language was applied to English grammar by a group of linguists who came to be known as structuralists. Their descrip tion of grammar is called structuralism. Like the anthropologists study ing the speech of Native Americans, the structuralists too recognized the importance of describing language on its own terms. Instead of assuming that English words could fit into the traditional eight word groups of Latin, the structuralists examined sentences objectively, paying particular attention to how words change in sound and spelling (their form) and how they are used in sentences (their function). You will see the result of that examination in the next chapter, where a clear distinction is drawn between the large open form classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) and the small closed structure classes, such as prepositions and conjunctions.

- 24. Chapter 1: The Stud'" of Grammar: An Overview 7 Another important feature of structuralism, which came to be called “new grammar,” is its emphasis on the systematic nature of English. The description of the form classcs is a good case in point. Their formal nature is systematic; for example, words that have a plural and possessive form are nouns; words that have both an -ed form (past tense) and an -ing form are verbs. For the structuralists, this systematic description of the language includes an analysis of the sound system (phonology), then the systematic combination of sounds into meaningful units and words (morphology), and, finally, the systematic combination of words into meaningful phrase structures and sentence patterns (syntax). Transformational Grammar. In the late 1950s, at a time when structur alism was beginning to have an influence on textbooks, a new approach came into prominence. Called transformationalgenerative grammar, this new linguistic theory, along with changes in the language arts curriculum, finally led to the diminishing influence of structuralism. Linguistic re search today carries forward what can only be called a linguistic revolution. The new linguistics, which began in 1957 with the publication of Noam Chomsky’s Syntactic Structures, deserves the label “revolutionary.” After 1957, the study of grammar would no longer be limited to what is said and how it is interpreted. In fact, the word grammar itself took on a new meaning, the definition we are calling Grammar 1: our innate, subconscious ability to generate language, an internal system of rules that constitutes our human language capacity. The goal of the new linguistics was to describe this internal grammar. Unlike the structuralists, whose goal was to examine the sentences we actually speak and to describe their systematic nature (our Grammar 2), the transformationalists wanted to unlock the secrets of language: to build a model of our internal rules, a model that would produce ail of the grammatical— and no ungrammatical—sentences. It might be useful to think of our built-in language system as a computer program. The transfor mationalists are trying to describe that program. For example, transformational linguists want to know how our internal linguistic computer can interpret a sentence such as I enjoy visiting relatives as ambiguous— that is, as having more than one possible meaning. (To figure out the two meanings, think about who is doing the visiting.) In Syntactic Structures, Chomsky distinguished between “deep” and “surface” structure, a concept that may hold the key to ambiguity. This feature is also the basis for the label transformational, the idea that meaning, generated in the deep structure, can be transformed into a variety of surface struc tures, the sentences we actually speak. During the past four decades the theory has undergone, and continues to undergo, evolutionary changes.

- 25. 8 Part I: introduction Although these linguistic theories reach far beyond the scope of class room grammar, there are several important concepts of transformational grammar that you will be studying in these chapters. One is che recog nition that a basic sentence can be transformed into a variety of forms, depending on intent or emphasis, while retaining its essential meaning— for example, questions and exclamations and passive sentences. Another major adoption from transformational grammar is the description of our system for expanding the verb in Chapter 4. THE ISSUE OF CORRECTNESS The structural linguists, who had as their goal the objective description of language, recognized that no one variety of English can lay claim to the label “best” or “correct,” that the dialects of all native speakers are equally grammatical. You won’t be surprised to learn that the structuralists, after describ ing the language of all native speakers as grammatical, were themselves called “permissive,” charged with advocating a policy of “anything goes.” After all, for three hundred years an im portant goal of school grammar lessons and textbooks had been to teach “proper” grammar. Proper grammar implies standards of correctness, and the structural ists appeared to be rejecting standards and ignoring rules. But what the structural linguists were actually doing was making a distinction between Grammar 2 and Grammar 3: the formal language patterns and “linguistic etiquette.” In his textbook English Sentences (Harcourt, 1962), Paul Roberts labeled the following sentences, which represent two dialects of English, equally grammatical: 1. Henry brought his mother some flowers. 2. Henry brung his mother some flowers. Roberts explains that if we prefer sentence 1, wc do so simply because in some sense we prefer the people who say sentence 1 to those who say sentence 2. We associate sentence 1with educated people and sentence 2 with uneducated people. . . . But mark this well: educated people do not say sentence 1 . . . because it is better than 2. Educated people say it, and that makes it better. ’J.hat’s all there is to it. (p. 7) The well-known issue of ain’ t provides another illustration of the dif ference between our internal rules of grammar and our external, social rules of usage, between our Grammar 1 and Grammar 3. You may have

- 26. Chapter 1: The Study of Grammar: An Overvieiv 9 assumed that pronouncements about ain’ t have something to do with in correct or ungrammatical English— but they don’t. The word itself, the contraction of am not, is produced by an internal rule, the same rule that gives us aren’ t and isn’ t. Any negative bias you may have against ain’ t is strictly a matter of linguistic etiquette. And, as you can hear for yourself, many speakers of English harbor no such bias. W ritten texts from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries show chat ain’ t was once a part of conversational English of educated people in England and America. It was sometime during the nineteenth century that the word became stigmatized for public spccch and marked a speaker as uneducated or ignorant. It’s still possible to hear ain’ t in public speech, but only as an attention-better: * O If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. You ain’t seen nothin’ yet. And of course it occurs in written dialogue and in written and spoken humor. But despite the fact that the grammar rules of millions of people produce ain’ t as part of their native language, for many others it carries a stigma. 1.1 The stigma attached to ain’ t has left a void in our language: We now have no first-person equivalent of the negative questions Isn’ t it? and Aren’ t they? You will discover how we have filled the void when you add the appropri ate tag-questions to three sentences. The tag-question is a common way we have of turning a statement into a question. Two examples will illustrate the structure: Your mother is a nice person, isn't she' Your brother is still in high school, isn’ t he* Now write the tag for these three sentences: 1. The weather is nice today,_______________? 2. You are my friend,_______________? 3. I am your friend,_______________? You’ll notice that you can turn those tag-questions into statements by reversing them. Here are the examples: She isn’ t. He isn’ t. *--- _ -- _ _""-W 1 - " Investigating Language

- 27. 10 Part I: Introduction Now reverse rhe three that you wrote: 1. . 2. _____________________ . 3. _______________ . In trying to reverse che third tag, you have probably discovered the prob lem that the banishment of ain’ t has produced. It has left us with something that sounds like an ungrammatical structure. Given the linguists’ definition of ungrammatical, something that a native speaker wouldn’t say, would you call “ Aren’ tl? ”ungrammatical? Explain. In summary, then, our attitude toward ain't is an issue about status, not grammar. We don’t hear ain’ t, nor do we hear rcgionalisms like I might could go and the car needs washed, in formal speeches or on the nightly news because they are not part of what we call “standard English.” Modern linguists may find the word standard objectionable when ap plied to a particular dialect, given that every dialect is standard within its own speech community. To label Roberts’s sentence 1 as standard may seem to imply that others are somehow inferior, or substandard. Here, however, we are using standard as the label for the majority dialect— or, perhaps more accurately, the status dialect— the one that is used in news casts, in formal business transactions, in courtrooms, in all sorts of pub lic discourse. If the network newscasters and the president of the United States and your teachers began to use ain’ t or brung on a regular basis, its status too would soon change. LANGUAGE VARIETY All of us have a wide range of language choices available to us. The words we choose and the way in which we say them are determined by the occasion—-by our listeners and our purpose and our topic. The way we speak with friends at the pizza parlor, where we use the current slang and jargon of the group, is not the same as our conversation at a formal banquet or a faculty reception. “Is it correct?” is probably rhe wrong ques tion to ask about a particular word or phrase. A more accurate question would be “Is it correct for this situation?” or “Is it appropriate?” In our written language, too, what is appropriate or effective in one sit uation may be completely out of place in another. Ihe language of email messages and texting arc obviously different from the language you use in a job-application letter. Even the writing you do in school varies from one class or one assignment to another. The personal essay you write for your composition class has a level of informality that would be inappropriate

- 28. Chapter I: Ihe Study o f Grammar: An Overview 11 for a business report or a history research paper. As with speech, the pur pose and the audience make all the difference. Edited American English is the version of our language that has come to be the standard for written public discourse— for newspapers and books and for most of the writing you do in school and on die job. It is the version of our language that this book describes, the written version of the status dialect as it has evolved through the centuries and continues to evolve. LANGUAGE CHANGE Another important aspect of our language that is closely related to the issue of correctness and standards is language change. Change is inevitable in a living organism like language. The change is obvious, of course, when we compare the English of Shakespeare or the King James Bible to our modern version. But we certainly don’t have to go back that far to see differences. The following passages are from two different translations of Pinocchio, the Italian children’s book written in the 1880s by Carlo Collodi. The two versions were published almost sixty years apart. You’ll have no trouble distinguishing the translation of 1925 from the one published in 1983: la. Fancy the happiness of Pinocchio on finding himself free! lb. Imagine Pinocchio’s joy when he felt himself free. 2a. Gallop on, gallop on, my pretty steed. 2b. Gallop, gallop, little horse. 3a. But whom shall 1ask? 3b. But who can I possibly ask? 4a. "Woe betide the lazy fellow. 4b. Woe to those who yield to idleness. 5a. Hasten, Pinocchio. 5b. Hurry, Pinocchio. 6a. W ithout adding another word, the marionette bade the good Fairy good-by. 6b. W ithout adding another word, the puppet said good-bye. to his good fairy. In both cases the translators are writing the English version of 1880 Italian, so the language is not necessarily conversational 1925 or 1983

- 29. English. In spice of that constraint, we can recognize— as you’ve prob ably figured out— that the first item in cach pair is the 1925 translation. Those sentences include words chat wc simply don’t have occasion to use anymore, words chac would sound out of place today in a conversation, or even in a fairy tale: betide, hasten, bade. The language of 1925 is sim ply not our language. In truth, the language of 1983 is not our language either. We can see and hear change happening all around us, especially if we consider the new words required for such fields as medicine, space scicnce, and e-commerce. 12 Part I: Introduction 1.2 The difference between the two translations in die first pair of Pinocchio sentences is connected to the word fancy, a word that is still common codav. Why did the 1983 translator use imagine instead? Whar has happened to fancy in the intervening decades? The third pair involves a difference in grammar rarher than vocabulary, the change from whom to who. What do you suppose today’s language critics would have to say about the 1983 translation? The last pair includes a spelling change. Check the dictionary to see which is “correct”—or is correctthe right word? The dictionary includes many words chac have more than one spelling. How do you know which one to use? Finally, provide examples to demonstrate chc accuracy of the assertion that the language of 1983 is not our language. LANGUAGE IN THE CLASSROOM How about che classroom? Should ceachers call acccncion to the dialect differences in their students’ speech? Should teachers “correct” chem? These are questions that the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) has addressed in a document callcd “Students’ Right to Their Own Language.” The NCTE has taken che position that teachers should respecc che dialects of their students. But teachcrs also have an obligation to teach students to read and wrice scandard English, che language of public discourse and of che workplace chat chose students are preparing to join. There are ways of doing so without making students feel that the language spoken in their home, the language produced by their own inrernal gram mar rules, is somehow inferior. Cercainly one way is co scudy language differences in an objeccive, nonjudgmencal way, to discuss individual and regional and ethnic differences. Teachers who use the technique called code-swicching have had notable success in helping students noc only co acquire standard English as a second dialect but also to understand in a Investigating Language

- 30. Chapter 1: The Study of Grammar: An Overview conscious way the underlying rules of their home language. (For informa tion on code-switching, see che book by Wheeler and Swords in the list for further reading chat follows rhis chapcer.) In 1994 che NCTE passed a resolution that encourages the incegra- cion of language awareness into classroom instruction and teacher prepa- racion programs. Language awareness includes examining how language varies in a range of social and cultural seccings; how people’s attitudes towards language vary across cultures, classes, genders, and generacions; how oral and wriccen language affects listeners and readers; how “correct ness” in language reflects social, political, and economic values; and how firsc and second languages are acquired. Language awareness also includes che teaching of grammar from a descriptive, racher chan a prescriptive, perspective. C t f A M 'E K j Key Terms Code-switching Correctness Descriptive grammar Dialccc Edited American English Grammar rules Grammatical Language change Language variety Linguistic etiquette Nonstandard dialect Prescriptive grammar Regionalisms Structuralism Transformational grammar Ungrammatical Usage rules For Further Reading on Topics in This Chapter Baron, Dennis E. Grammar and Good Taste: Reforming the American Language. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1982. Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia o fLanguage. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1987. Haussamen, Brock. Revising the Rides: Traditional Grammar and Modern Linguistics. 2nd cd. Dubuque, LA: Kendall-Hunt, 1997. Hunter, Susan, and Ray Wallace, eds. Tfje Place o f Grammar in Writing Instruction: Past, Present, Future. Portsmouth, NH: Bovnton/Cook, 1995.

- 31. Part I: Introduction Joos, Martin. The Five Clocks. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1967. Kut7., Eleanor. Language and Literacy: Studying Discourse in Communities and Classrooms. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook, 1997. McCrum, Robert, Robert MacNeil, and William Cran. The Stor)’ of English. 3rd rev. cd. New York: Penguin Books, 2003. Pinker, Steven. 1be Language Instinct. New York: William Morrow, 1994. Pinker, Steven. 'Ihe Stuffof Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature. New York: Viking, 2007. Schuster, Edgar H. Breaking the Rules: Liberating Writers Through Innovative Grammar Inspection. Portsmouth, NH: Hcincmann, 2003. Wheeler, Rebecca S., and Rachel Swords. Code-Switching: Teaching Standard English in Urban Classrooms. Urbana, II.: National Council of Teachers of English, 2006. Wolfram, Walt. Dialects and American English. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics, 1991.

- 32. PART II The Grammar of Basic Sentences du might have been surprised to learn, when you read the introduc tion to Part I, that you’re already an expert in grammar— and have been since before you started school. Indeed, you’re such an expert that you can generate completely original sentences with chose internal gram mar rules of yours, sentences thar have never before been spoken or writ ten. Here’s one to get you started; you can be quite sure that it is original: At this very moment, I, [Insert your name], am reading page 15 of the ninth edition of Understanding English Grammar. Perhaps even more surprising is the fact that the number of such sentences you can produce is infinite. When you study the grammar of your native language, then, you are studying a subject you already “know”; so rather than learning grammar, you will be "learning about” grammar. If you’re not a native speaker, you will probably be learning both grammar and “about” grammar; the mix will depend on your background and experience. It’s important chat you understand what you arc bringing to this course— even though you may have forgotten all chose “parts of speech” labels and definitions you once consciously learned. The unconscious, or subconscious, knowledge chac you have can help you if you will lec ic. We will begin the scudy of grammar by examining words and phrases in Chapter 2. Then in Chapter 3 we take up basic sentence patterns, the underlying framework of sentences. A conscious knowledge of the basic patcerns provides a foundation for the expansions and variations that come later. In Chapter 4 we examine the expanded verb, the system of auxiliaries that makes our verbs so versatile. In Chapter 5 we look at ways co change sentence focus for a variety of purposes. 15

- 33. APTf^ 2 Words and Phrases C H A P T E R P R E V IE W The purpose of this chapter is to review words and phrases. It will also introduce you to some of the language for discussing language— that is, the terms you will need for thinking about sentence structure. Pay attention to the items in bold face; they constitute your grammar vocabu lary and are defined in the Glossary, beginning on page 349. This review will lay the groundwork for the study of the sentence patterns and their expansions in the chapters that follow. By the end of this chapter, you will be able to • Distinguish between the form classes and the structure classes of words. • Identify examples of the four form classes: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. • Identify determiners and headwords as basic components of noun phrases. • Recognize the subject— predicate relationship as the core structure in all sentences. • Identify the structure and use ofprepositionalphrases. • Use your subconscious knowledge of grammar to help analyze and understand words and phrases. THE FORM CLASSES ihe four word classes that wc call form classes—nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs—are special in many ways. If you were assigned to look around your classroom and make a list of what you see, the words in your list would undoubtedly be the names of things and people: books, desks, 16

- 34. Chapter 2: Words and Phrases 17 windows, shelves, shoes, sweatshirts, Nina, Ella, Ted, Hector, Professor Watts. Those labels— those names of things and people— are nouns. (As you may know, noun is the Latin word for “name.”) And if you were assigned to describe what your teacher and classmates are doing at the moment— sitting, talking, dozing, smiling, reading—you’d have a list of verbs. We can think of those two sets— nouns and verbs— along with adjec tives and adverbs (the /;zgbook; sitting quietly) as special. They are the content words of the language. And their numbers make them special: Ihcsc four groups constitute over 99 percent of our vocabulary. They are also different from other word classes in that they can be identified by their forms. Each of them has, or can have, particular endings, or suffixes, which identify them. And that, of course, is the reason for the label “form classes.” NOUNS AND VERBS Here are two simple sentences to consider in terms of form, each consist ing of a noun and a verb: Cats fight. Marv laughed. You may be familiar with the traditional definition of noun— “a word that names a person, place, or thing [or animal]”; that definition is based on meaning. 'Ihe traditional definition of verb as an “action word” is also based on meaning. In our two sentences those definitions certainly work. But notice also the clues based on form: in the first one, che plural suffix on the noun cat; in the second, the past-tense suffix on the verb laugh. The plural is one of two noun endings that we call inflections; the other is the possessive case ending, the apostrophe-plus-s (the cat’ spaw)—or, in the case of most plural nouns, just the apostrophe after the plural marker (.several cats’paws). When the dictionary identifies a word as a verb, it lists chree forms: the present tense, or base form (laugh)-, the past tense [laughed)', and the past participle {laughed). Ihese three forms arc traditionally referred co as che verb’s “three principal pares.” The base form is also known as the infinitive; ic is ofcen wrircen with to (to laugh). All verbs have these forms, along with two more— the -s form (laughs), and the -ing form (laughing). We will take these up in Chapter 4, where we study verbs in detail. But for now, let’s revise the traditional definitions by basing them not on the meaning of the words but rather on their forms: A noun is a word that can be made plural and/orpossessive. A verb is a word that can show tense, such aspresent and past.

- 35. 18 Part II: The Grammar o fBasic Sentences THE N O U N PHRASE The term noun phrase may be new co you, alchough you’re probably familiar with the word phrase, which traditionally refers to any group of words that functions as a unit within the sentence. Buc somccimcs a single word will function as a unit bv itself, as in our two earlier examples, where CA IS and Mary function as subjects in their sentences. For this reason, wc arc going co alter chat traditional definition ofphrase to include single words: A phrase is a word or group o f words thatfunctions as a unit within the sentence. A phrase will always have a head, or headword; and as you might expect, the headword of the noun phrase is a noun. Most noun phrases (NPs) also include a noun signaler, or marker, called a determiner. Here are three NPs you have seen in this chapcer, with their headwords under lined and their determiners shown in italics: the headword a single word the traditional definition As two of the examples illustrate, the headword may also be preceded by a modifier. The most common modifier in preheadword position is the adjective, such as single and traditional. You will be studying about many ocher scruccures as well chac funccion che way adjectives function, as modifiers of nouns. As you may have noticed in the three examples, the opening deter miners are the articles a and the. Though they are our most common determiners, ocher word groups also function as determiners, signaling noun phrases. For example, che funccion of possessive nouns and posses sive pronouns is almosc always chac of decerminer: M aiy’ s boyfriend his apartment Anocher common word category in che decerminer slot is the demonstrative pronoun— this, that, these, those: this old house these expensive sneakers Because noun phrases can be single words, as we saw in our earlier ex amples (Catsfight, Mary laughed), ic follows chat not all noun phrases will have determiners. Proper nouns, such as che names of people and places

- 36. Chapter 2: Words and Phrases 19 [Mary) and ccrtain plural nouns {cats), arc among the most common that appear without a noun signaler. In spice of these exceptions, however, it is accurate to say that most noun phrases do begin with determiners. Likewise, it’s accurarc to say— and important to recognize— that whenever you encounter a determiner you can be sure you are at the beginning ofa noun phrase. In other words, articles (a, an, the) and ccrtain other words, such as possessive nouns and pronouns, demonstrative pronouns, numbers, and another subclass of pronouns called indefinite pronouns (e.g., some, many, both, each, every), tell you that a noun headword is on the wav. We can now identify three defining characteristics of nouns: A noun is a word that can be made plural and!or possessive; it occupies the headwordposition in the noun phrase; it is usually signaled by a determiner. In the study of syntax, which you are now undertaking, you can’t help but notice the prevalence of noun phrases and their signalers, the determiners. The following six scntcnccs include sixteen noun phrases. Your job is co identify uhcir determiners and headwords. Note: Answers ro the exercises arc provided, beginning on page 371. 1. Ihe students rested after their long trip. 2. Our new neighbors across the hall became our best friends. 3. Mickey’s roommate studies in the library on che weekends. 4. A huge crowd lined the streets for the big parade. 5. This new lasagna recipe feeds an enormous crowd. 6. Jessica made her new boyfriend some cookies. THE VERB PHRASE As you would expect, the headword of a verb phrase, or VP, is the verb; the other components, if any, will depend in part on whether the verb is transitive (The cat chased the mouse) or intransitive (Catsfight). In most sentences, the verb phrase will include adverbials {Mary laughed loudly). In Chapter 3 you will be studying verb phrases in detail because it is the

- 37. 20 Part II: The Grammar ofBasic Sentences variations in the verb phrases, the sentence predicates, that differentiate the sentence patterns. As we saw with the noun phrase, it is also possible for a verb phrase to be complete with only the headword. O ur two earlier examples— Cats fight-, Mary laughed—illustrate instances of single-word noun phrases, which are fairly common in most written work, as well as single-word verb phrases, which are not common at all. In fact, single-word verb phrases as predicates are very rare. So far in this chapter, none of the verb phrases we have used comes close to the brevity of those two sample sentences. NP + VP = S "Ihis formula— NP + VP S— is another wray of saying “Subject plus Predicate equals Sentence.” Our formula with the labels NP and VP sim ply emphasizes the form of those two sentence parts. The following dia gram includes both labels, and their form and function: SENTENCE Noun Phrase Verb Phrase (Subject) (Predicate) Using what you have learned so far about noun phrases and verb phrases— as well as your intuition— you should have no trouble recog nizing the two parts of the following sentences. You’ll notice right away that the first word of the subject noun phrase in all of the sentences is a determiner. Our county commissioners passed a new' ordinance. The mayor’s husband argued against the ordinance. The mayor was upset with her husband. Some residents of the community spoke passionately for the ordinance. The merchants in town are unhappy. This new7lawrprohibits billboards on major highways. As a quick review' of noun phrases, identify the headwords of the subject noun phrases in the six sentences just listed:

- 38. Chapter 2: Words and Phrases 21 Given your understanding of noun phrases, you probably had no dif ficulty identifying those headwords: commissioners, husband, mayor, residents, merchants, law. In the exercise that follows, you are instructed to identify the two parts of those six sentences to determine where the subject noun phrase ends. This time you’ll be using your subconscious knowledge of pronouns. You have at your disposal a wonderful tool for figuring our the line between the subject and the predicate: Simply substitute a personal pronoun [I,you, he, she, it, they) for the subject. You saw these example sentences in Exercise 1: Examples: This new lasagna recipc feeds an enormous crowd. It feeds an enormous crowd. Our new neighbors across the hall became our best friends. They became our best friends. Now underline the subject; then substitute a pronoun for the subject of these sentences you read in the previous discussion: 1. Our county commissioners passed a new ordinance. 2. The mayor’s husband argued against the ordinance. 3. The mayor was upset with her husband. 4. Some residents of the community spoke passionately for the ordinance. 5. The merchants in town are unhappy. 6. This new law prohibits billboards on major highways. As your answers no doubt show, the personal pronoun stands in for the entire noun phrase, not just the noun headword. Making that substitu tion, which you do automatically in speech, can help you recognize not only the subject-predicate boundary but the boundaries of noun phrases throughout the sentence.

- 39. 22 Part II: 'Ihe Grammar ofBasic Sentences Recognition of this subject-predicate relationship, the common ele ment in all of our sentences, is the first step in the study of sentence structure. Equally im portant for the classification of sentences into sentence patterns is the conccpt of the verb as the central, pivotal slot in the sentence. Before moving on to the sentence patterns in Chapter 3, however, we will look briefly at the other two form classes, adjectives and adverbs, which, like nouns and verbs, can ofren be identified by [heir forms. We will then describe the prepositional phrase, perhaps our most common modifier, one that adds information to boch the noun phrase and the verb phrase. ADJECTIVES AND ADVERBS The other two form classes, adjectives and adverbs, like nouns and verbs, can usually be recognized by their form and/or by their position in the sentence. Ihe inflectional endings that identify adjectives and some adverbs arc -er and -est, known as the comparative and superlative degrees: Adjective Adverb big near bigger nearer biggest nearest When the word has two or more syllables, [he comparative and superlative markers are generally more and most rather than the suffixes: beautiful quickly more beautiful more quickly most beautiful most quickly Another test of whether a word is an adjective or adverb, as opposed to noun or verb, is its ability to pattern with a qualifier, such as very: very beautiful very quickly You’ll notice that these tests (the degree endings and very) can help you differentiate adjectives and adverbs from the other two form classes, nouns and verbs, but they do not help you distinguish the two word classes from each other. There is one special clue about word form that we use to help us identify adverbs: the -ly ending. However, this is not an inflectional suffix like -er or -est. When we add one of these to an adjective— happier, happiest—the word remains an adjective (just as a noun with the plural inflection added

- 40. Chapter 2: Words and Phrases 23 is still a noun). In contrast, the -ly ending that makes adverbs so visible is actually added to adjcctives to turn them into adverbs: Adjective Adverb quick + ly = quickly pleasant + ly = pleasantly happy + ly = happily Rather than inflectional, the -ly is a derivational suffix: It enables us to derive adverbs from adjectives. Incidentally, the -ly means “like”: quickly quick-like; happily = happy-like. And because we have so many adjectives that can morph into adverbs in this way— many thousands, in fact— we arc not often mistaken when we assume that an -ly word is an adverb. (In Chapter 12 you will read about derivational suffixes for all four form classes.) In addition to these “adverbs of manner,” as the -ly adverbs are called, we have a selection of other adverbs that have no clue of form; among them are then, now, soon, here, there, everywhere, afterivard, often, some times, seldom, always. Often the best way to identify an adverb is by the kind of information it supplies to the sentence— information of time, place, manner, frequency, and the like; in other words, an adverb answers such questions as where, when, why, how, and how often. Adverbs can also be identified on the basis of their position in the predicate and their movability. As you read in the discussion of noun phrases, the slot between the determiner and the headword is where we find adjectives: this new rccipe an enormous crowd Adverbs, on the other hand, modify verbs and, as such, will be part of the predicate: Some residents spoke passionately tor the ordinance. Mario suddenly hit the brakes. However, unlike adjectives, one of the features of adverbs that makes them so versatile for writers and speakers is their movability: 'Ihey can often be moved to a different place in the predicate— and they can even leave the predicate and open the sentence: Mario hit the brakes suddenly. Suddenly Mario hit the brakes.

- 41. Bear in mind, however, that some adverbs are more movable than others. We probably don’t want to move passionately to the beginning of its sentence. And in making the decision to move the adverb, we also want to consider the context, the relation of the sentence to the others around it. 24 Part IT: 'the Grammar of Basic Sentences 2.1 Your job in this exercise is to experiment with the underlined adverbs to discover how movable they are. How many places in the sentence will they fit? Do you and your classmates agree? 1. I have finally finished my report. 2. Maria has now accumulated sixty credits towards her degree. 3. The hunters moved stealthily through the woods. 4. The kindcrgartncrs giggled quietly in the corner. 5. Mv parents occasionally surprise me with a visit. 6. Our soccer coach will undoubtedly expect us to practice tomorrow. 7. I occasionally iog nowadays. 8. Ihe wind often blows furiously in lanuarv. PREPOSITIONAL PHRASES Before going on to sentence patterns, let’s take a quick look at the prepo sitional phrase, a two-part structure consisting of a preposition followed by an object, which is usually a noun phrase. Prepositions are among the most common words in our language. In fact, the paragraph you are now reading includes nine different prepositions: before, to, at, o f(three times), by, among, in, throughout, and as (twice). Prepositional phrases show up throughout our sentences, sometimes as part of a noun phrase and sometimes as a modifier of the verb. Because prepositional phrases are so common, you might find it helpful to review the lists of prepositions in Chapter 13 (pp. 274, 276). As a modifier in a noun phrase, a prepositional phrase nearly always follows the noun headword. Its purpose is to make clear the identity of the noun or simply to add a descriptive detail. Several of the noun phrases you saw in Rxercise 1 include a prepositional phrase: Our new neighbors across the hall became our best friends. Investijating Language

- 42. Chapter 2: Words and Phrases 25 Here the across phrase is part of the subject, functioning like an adjective, so wc call it an adjectival prepositional phrase; it tells “which neighbors” we’re referring to. In a different sentence, that same prepositional phrase could function adverbially: Our good friends live across the hall. Here the purpose of the across phrase is to tell “where” about the verb live, so we refer to its function as adverbial. Here’s another adverbial preposi tional phrase from Exercise 1: The students rested after their long trip. Here the preposicional phrase tells “when”— another purpose of adverbi- als. And there’s one more clue that this prepositional phrase is adverbial. It could be moved to the opening of the sentence: i Jeer their long trip, the students rested. Remember that the nouns adjective and adverb name word classes: They name forms. W hen we add that -al or -ial suffix— adjectival and adverbial—they become the names of functions— functions that adjec tives and adverbs normally perform. In other words, the terms adjectival and adverbial can apply to structures other than adjectivcs and adverbs— such as prepositional phrases, as we have just seen: Modifiers ofnouns are called adjectivals, no matter what theirform. Modifiers ofverbs are called adverbials, no matter what theirform. In the following sentences, some of which you have seen before, identify the function of each of the underlined prepositional phrases as either adjectival or adverbial: 1. A huge crowd of students lined the streets for the big parade. 2. Mickey’s roommate studies in the library on the weekends. 3. Some residents of the community spoke passionately for the ordinance. 4. The merchants in town were unhappy. 5. In August my parents moved to Portland. 6. On sunny days we lounge on the lawn between classes.

- 43. 26 Part II: The Grammar ofBasic Sentences 2.2 A. Make each list of words into a noun phrase and then use the phrase in a sentence. Compare your answers with your classmates’—the NPs should all be the same (with one exception); the sentences will vary. 1. table, the, small, wooden 2. my, sneakers, roommate’s, new 3. cotton, white, t-shirts, the, other, all 4. gentle, a, on the head, tap 5. books, those, moldy, in the basement 6. the, with green eyes, girl Did you discover the item with two possibilities? B. Many words in English can serve as either nouns or verbs. Here arc some examples: Tmade a promise to my boss, (noun) Ipromised to be on time for work, (verb) He offered to help us. (verb) We accepted his offer, (noun) Write a pair of short sentences for each of the following words, dem onstrating that they can be either nouns or verbs: visit plant point feature audition THE STRUCTURE CLASSES In addition to the form classes, so far in this chapter you have learned labels for three of our structure classes: 1. Determiner, a word that marks nouns. In the section headed “The Noun Phrase,” you learned that the function of articles (a, an, the), possessive nouns and pronouns (his, M ary’ s, etc.), demonstrative pronouns (this, that, these, those), and indefinite pronouns (some, both, each, ctc.) is to introduce noun phrases. In other words, when you see the or my or this or some, you can be very sure that a noun is coming. 2. Qualifier, a word that marks— qualifies or intensifies— adjectives and adverbs: rather slowly, very sure. 3. Preposition, a word, such as to, of, for, by, and so forth, that combines with a noun phrase to produce an adverbial or adjecti val modifier. Prepositions are listed on pages 274, 276. Investigating Language

- 44. Chapter 2: Words and Phrases 27 In contrast to the large, open form classes, the structure classes are small and, for the most part, closed classes. As you read in the description of the form classes, those open classes constitute 99 percent of our language— and they keep getting new members. However, although the structure classes may be small, they are by far our most frequently used words. And we couldn’t get along without them. In Chapter 3 you will be introduced to several other structure classes as you study the sentence patterns. You will find examples of all of them in Chapter 13. CHAPTER 2 Key Terms In this chapter you’ve been introduced to many basic terms that describe sentence grammar. This list may look formidable, but some of the terms were probably familiar already; those that are new will become more familiar as you continue the study of sentences. Adjectival Adjective Adverb Adverbial Article Comparative degree Degree Demonstrative pronoun Derivational suffix Determiner Form classes Headword Indefinite pronoun Inflection Noun Noun phrase Past tense Personal pronoun Phrase Plural Possessive case Predicate Preposition Prepositional phrase Pronoun Qualifier Structure classcs Subject Suffix Superlative degree Verb Verb phrase

- 45. A PT£ 3 Sentence Patterns C H A P T E R P R E V IE W This chapter will extend your study of sentence structure, which began in the previous chaptcr with its focus on the noun phrase and the verb phrase. Although a speaker can potentially produce an infinite num ber of sentences, the systematic structure of English sentences and the lim ited num ber of elements in these structures make this study possible. Ten sentence patterns account for the underlying skeletal structure of almost all the possible grammatical sentences. Your study of these basic patterns will give you a solid framework for understanding the expanded sentences in the chapters that follow. By the end of this chapter, you will be able to • Recognize four types of verbs: be, linking, intransitive, and transitive. • Identify and diagram the ten basic sentence patterns. • Distinguish among subject complements, direct objects, indirect objects, and object complements. • Identify the adverbs and prepositional phrases that fill out the ten patterns. • Understand and use phrasal verbs and simple compound structures. • Recognize four types of sentences: declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamatory. 28

- 46. Chapter 3: Sentence Patterns 29 SUBJECTS AND PREDICATES The first step in understanding the skeletal structure of the sentence pat terns is to recognize the two parts they all have in common, the subject and the predicate: SENTENCE Subject Predicate The subject, of the sentence, as its name suggests, is generally what the sentence is about— its topic. The predicate is what is said about the subject. 'lhc terms subject, and predicate refer to sentence functions, or roles. But wc can also describe those sentence functions in terms of form: SKNTKNCK NP VP (Noun Phrase) (Verb Phrase) In other words, the subject slot is generally filled by a noun phrase, the predicate slot by a verb phrase. In later chapters we will see sentences in which structures other than noun phrases fill the subject slot.; however, the predicate slot is always filled by a verb phrase. Recognizing this subject-predicate relationship, the common element in all of our sentences, is the first step in the study of sentence structure. Hqually important for the classification of sentences into sentence patterns is the concept, of the verb as the central, pivotal slot in the sentence. In the following list of the ten patterns, the subjects are identical ( Ihe students) to emphasize that the ten categories arc determined by variations in the predicates, variations in the verb headword, and in the structures following the verb. So although we call these basic forms sentence patterns, a more accurate label might be predicate patterns. We should note that this list of patterns is not the only way to orga nize the verb classes: Some descriptions include fifteen or more patterns. However, rather than adding more patterns to our list, we account for the sentences that vary somewhat from the general pattern by considering them exceptions.

- 47. 30 Part II: Tl> e Grammar ofBasic Sentences SENTENCE NP ^ VP (Subject) (Predicate) I. The students are upstairs. II. The students are diligent. III. The students are scholars. IV. The students seem diligent. V. The students became scholars. VI. The students rested. VII. The students organized a dance marathon. Vlll. The students gave the professor their homework. IX. The students consider the teacher intelligent. X. The students consider the coursc a challenge. THE SENTENCE SLOTS One way to think about a sentence is to picture it as a series of positions, or slots. In the following chart, where all the slots are labeled, you’ll see that the first one in ever}7pattern is the subject, and the second— the first posi tion in the predicate— is the main verb, also called the predicating verb. Because the variations among the sentence patterns are in the predicates, we group the ten patterns according to their verb types: the be patterns, the linking verb patterns, the intransitive verb pattern, and the transitive verb patterns. You’ll notice that the number of slots in the predicate varies: Six of the patterns have two, but Pattern VI has only one slot, and three of the transitive patterns, VIII to X, each have three. The label in parentheses names the function, the role, that the slot performs in the sentence. ’ihe subscript numbers you see in some of the patterns in the chart that follows show the relationship between noun phrases: Identical numbers— such as those in Patterns III and V, where both numbers are 1— mean that the two noun phrases have the same referent; different numbers— such as those in Pattern VII, where the numbers are 1 and 2— denote different referents. Referent means the thing (or person, event, concept, and so on) that the noun or noun phrase stands for. 'lhis list of patterns, with each position labeled according to its form and its role in the sentence, may look formidable at the moment. But don’t worry— and don’t try to memorize all this detail. It will fall into place as you come to understand the separate patterns.

- 48. Chapter 3: Sentence Patterns 31 The Be Patterns I NP be ADV/TP (subject) (predicating verb) (adverbial of time or place) T})e students are upstairs II NP be ADJ (subj) (pred vb) (subject complement) The students are diligent III NP, be NP, (subj) (pred vb) (subj comp) The students are scholars The Linking Verb Patterns IV NP linking verb ADJ (subj) (pred vb) (subj comp) Ihe students seem diligent V NP, Ink verb NP, (subj) (pred vb) (subj comp) 7he students became scholars The Intransitive Verb Pattern VI NP intransitive verb (subj) (pred vb) The students rested The Transitive Verb Patterns VII NP, transitive verb n p 2 (subj) (pred vb) (direct object) The students organized a dance marathon VIII NP1 trans verb NP; NP, (subj) (pred vb) (indirect object) (dir obj) The students gave theprofessor their homework IX NP, trans verb n p 2 ADJ (subj) (pred vb) (dir obj) (obj comp) The students consider the teacher intelligent X NP, trans verb NP, NP, (subj) (pred vb) (dir obj) (obj comp) 7he students consider ihe course a challenge

- 49. 3 2 Part II: Ihe Grammar ofBasic Sentences THE B E PATTERNS The first three formulas state that when a form of be serves as the main, or predicating, verb, an adverbial of time or place (Pattern I), or an adjectival (Pattern II), or a noun phrase (Pattern III) will follow it. The one excep tion to this rule— and, by the way, we can think of the sentence patterns as descriptions of the rules that our internal computer is programmed to follow— is a statement simply affirming existence, such as “1 am.” Aside from this exception, Patterns 1 through III describe all the sentences in which a form of be is the main verb. (Other one-word forms of be are am, is, are, was, were; and the expanded forms, described in Chapter 4, include have been, was being, might be, and will be.) Pattern I: N P be AD V/TP The students are upstairs The teacher is here. Ihe last performance wa< The ADV in the formula stands for adverbial, a modifier of the verb. The ADV that follows be is, with certain exceptions, limited to when and where information, so in the formula for Pattern I we identify the slot as ADV/TP, meaning “adverbial of time or place.”1In the sample sentences upstairs and /^redesignate place;yesterday designates time. 'Ihe diagram of Pattern I shows the adverb below' the verb, which is where all adverbials are diagrammed. In the following Pattern I sentences, the adverbials of time and place are prepositional phrases in form; The next performance is on Monday. The students are in the library. The diagram for the adverbial prepositional phrase is a two-part frame work with a slanted line for the preposition and a horizontal line for the object; ; yesterday. students arc A V * Sl -c Question 4 iil the end of this chapter for examples of these exceptions.