1 Assessment Task – Tutorial Questions Assignment 1 .docx

- 1. 1 Assessment Task – Tutorial Questions Assignment 1 Unit Code: HA1020 Unit Name: Accounting Principles and Practices Assignment: Tutorial Questions Assignment 1 Due: 11:30pm 15th May 2020 Weighting: 25% Total Assignment Marks: 50 Marks Purpose: This assignment is designed to assess your level of knowledge of the key topics covered in this unit Unit Learning Outcomes Assessed: 1. Understand the logic and assumptions of accounting procedures; 2. Record business transactions in the journals and ledgers that make up a business accounting system; 3. Prepare financial statements; and 4. Analyse and interpret financial statements.

- 2. Description: Each week students were provided with three tutorial questions of varying degrees of difficulty. These tutorial questions are available in the Tutorial Folder for each week on Blackboard. The Interactive Tutorials are designed to assist students with the process, skills and knowledge to answer the provided tutorial questions. Your task is to answer a selection of tutorial questions from weeks 1 to 5 inclusive and submit these answers in a single document. The questions to be answered are: Week 1 Question (10 marks) (Note this question is 1.3 in the Pre-recorded Tutorial Questions) Compare and contrast Financial Accounting with Management Accounting. Specify at least three (3) areas where Financial Accounting and Management Accounting are different. Support your answer with examples. (10 marks)

- 3. 2 Week 2 Question (10 marks) (Note this question is 2.2 in the Pre-recorded Tutorial Questions) Select two (2) of the following four (4) financial accounting assumptions listed below and explain in your own words the meaning of each one you have selected: (10 marks) (a.) accounting entity (b.) accounting period (c.) monetary (d.) historical Week 3 Question (10 marks) (Note this question is 3.2 in the Pre-recorded Tutorial Questions) Which of the following events listed below results in an accounting transaction for Clothing Ltd? State a reason if it is not an accounting transaction. 1. Clothing Ltd signed a contract to hire a new store manager for a salary of $150,000 per annum. The manager will start work next month.

- 4. 2. The founder of Clothing Ltd., who is also a major shareholder, purchased additional stock in another company. 3. Clothing Ltd borrowed $230,000 from a local bank. 4. Clothing Ltd purchased a sewing machine, which it paid for by signing a note payable. 5. Clothing Ltd issued 10,000 shares to a private investor, who is also a car business owner, in return for a new delivery truck. 6. Two investors in Clothing Ltd sold their stock to another investor. 7. Clothing Ltd ordered some fabric to be delivered next week. 8. Clothing Ltd lent $250,000 to a member of the board of directors.

- 5. 3 Week 4 Question (10 marks) (Note this question is 4.3 in the Pre-recorded Tutorial Questions) The financial year end for Riverwood Ltd is 30 June. a. Prepaid insurance as at 1 July 2015 was $4,000. This represents the cost of one year’s insurance policy that expires on 30 June 2016. b. Commissions to sales personnel for the five day working week ending 2 July 2016, totaling $9,600, will be paid on 2 July. c. Sales revenue for the year included $570 of customer deposits for products that have not yet been shipped to them. d. A total of $900 worth of stationery was charged to the office supplies expense during the year. On 30 June about $490 worth of stationery is still considered useful for next year. e. The company has a bank loan and pays interest annually (in arrears) on 31 December. The estimated total interest cost for the calendar year ended 31 December 2016 is $500.

- 6. Required: (a.) Show the effect of each of the situations above (a. – e.) on the accounting equation on 30 June 2016. (5 marks) (b.) Provide the adjusting journal entry for each of the situations above (a. – e.) on 30 June 2016. (5 marks) 4 Week 5 Question (10 marks)

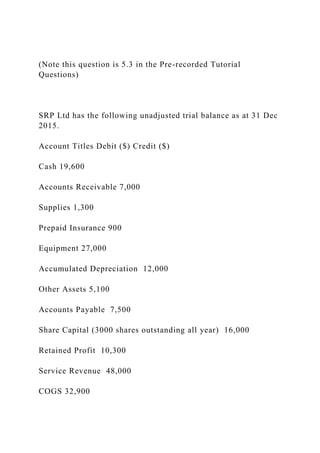

- 7. (Note this question is 5.3 in the Pre-recorded Tutorial Questions) SRP Ltd has the following unadjusted trial balance as at 31 Dec 2015. Account Titles Debit ($) Credit ($) Cash 19,600 Accounts Receivable 7,000 Supplies 1,300 Prepaid Insurance 900 Equipment 27,000 Accumulated Depreciation 12,000 Other Assets 5,100 Accounts Payable 7,500 Share Capital (3000 shares outstanding all year) 16,000 Retained Profit 10,300 Service Revenue 48,000 COGS 32,900

- 8. Total 93,800 93,800 Note: Data not yet recorded as at 31 Dec 2015 includes the following five (5) transactions: 1) Depreciation expense for 2015 was $3,000. 2) Insurance expired during 2015 was $450. 3) Wages earned by employees but not yet paid on 31 December 2015 was $2,100. 4) The supplies count on 31 December 2015 reflected $800 remaining supplies on hand to be used in 2016. 5) Income tax expense was $3,150. Required: (10 marks) 1) Record the 2015 adjusting entries. 2) Prepare an income statement and a classified balance sheet for 2015 to include the effect of the five (5) transactions listed above. 3) Prepare closing entries.

- 9. 5 Submission Directions: The assignment has to be submitted via Blackboard. Each student will be permitted one submission to Blackboard only. Each student needs to ensure that the document submitted is the correct one. Academic Integrity Academic honesty is highly valued at Holmes Institute. Students must always submit work that represents their original words or ideas. If any words or ideas used in a class posting or assignment submission do not represent the student’s original words or ideas, the student must cite all relevant sources and make clear the extent to which such sources were used. Written assignments that include material similar to course reading materials or other sources should include a citation including source, author, and page number. In addition, written assignments that are similar or identical to those of another student in the class is also a violation of the Holmes Institute’s Academic Conduct and Integrity Policy. The consequence for

- 10. a violation of this policy can incur a range of penalties varying from a 50% penalty through to suspension of enrolment. The penalty would be dependent on the extent of academic misconduct and the student’s history of academic misconduct issues. All assessments will be automatically submitted to Safe-Assign to assess their originality. Further Information: For further information and additional learning resources, students should refer to their Discussion Board for the unit. CHAPTER 8 Searching for Mortgage Information Online 131 Chapter 8 IN THIS CHAPTER » Looking at some safe surfing ideas » Checking out mortgage sites Searching for Mortgage Information Online Computers, tablets, and smartphones are amazing tools. Used wisely, they may save you time and money. However, like other tools (such as a ham-mer), used incorrectly (remember the last time you whacked your finger with a hammer?) or for the wrong purpose (tapping a glass

- 11. window comes to mind), today’s technology can cause more harm than good. Some people have mistaken assumptions about using their computers and tablet or phone apps to help them make important financial decisions. Some believe and hope that fancy technology can solve their financial problems or provide unique insights and vast profits. Often, such erroneous musings originate from propa- ganda put forth through “fake news” or social media about how all your problems can easily be solved if you just have the right app, spend more time on particular websites, and so on. As computers, technology, and apps continue to proliferate, we take seriously our task of explaining how, where, and when to use the Internet to help you make important mortgage decisions. In this chapter, we highlight key concepts and issues for you to understand as well as list a few of our favorite websites. Griswold, R. S., Tyson, E., & Tyson, E. (2017). Mortgage management for dummies. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com Created from apus on 2020-05-04 20:26:39. C op yr ig

- 13. ht s re se rv ed . 132 PART 3 Landing a Lender Obeying Our Safe Surfing Tips Before we get to specific sites that are worthy of your time, in this section we provide an overview of how we suggest using (and not being abused by) your mortgage-related web surfing or cure-all app. Specific sites, and especially apps, will come and go, but these safe surfing tips should assist you with assessing any site or app that you may stumble upon. Shop to find out about rates and programs The best reason that we can think of to access the Internet when you’re looking for a mortgage is to discover more about the going rate for the various types of loans you’re considering. Despite all the cautions we raise in this chapter, shop- ping for a mortgage online has some attractions:

- 14. » No direct sales pressure: Because you don’t speak or meet with a mortgage officer (who typically works on commission) when you peruse mortgage rates online, you can do so without much pressure. That said, some sites and apps are willing to give out specific loan information only after you reveal a fair amount of information about yourself, including how to get in touch with you. However, on one site where you must register (with all your contact informa- tion and more) to list your loan desires, take a look at how the site pitches itself to prospective mortgage lenders: “FREE, hot leads! Every lead is HOT, HOT, HOT because the borrower has paid us a fee to post their loan request.” Although the advantages of online shopping are many, being savvy and discrete with who and how you contact prospective lenders is worthy of a cautionary reminder. You may think you’re the one shopping, but on many sites and apps, you are the one being “sold” to aggressive marketers of loan products that may not be what you need. Worse yet, many of these unscrupu- lous hucksters don’t even have the loan products and terms they tease on their website and their real goal is to lure you in and then turn around and sell your information to others. You’ll soon find yourself inundated with unwanted emails, texts, and even phone calls.

- 15. » Shop when you like: Because most people work weekdays when lenders and mortgage brokers are available, squeezing in calls to lenders is often difficult. Thus, another advantage of mortgage Internet shopping is that you can do it any time of any day when it’s convenient for you. Just be careful that you don’t provide personal information to anyone unless you’re sure you want him to contact you. Griswold, R. S., Tyson, E., & Tyson, E. (2017). Mortgage management for dummies. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com Created from apus on 2020-05-04 20:26:39. C op yr ig ht © 2 01 7. J oh n

- 17. CHAPTER 8 Searching for Mortgage Information Online 133 Quality control is often insufficient Particularly at sites where lenders simply pay an advertising fee to be part of the program, you should know that quality control may be nonexistent or not up to your standards. “We make your loan request available to every online lender in the world,” boasts one online mortgage listing service. We don’t know too many bor- rowers willing to work with just any old mortgage company! Some sites don’t check to see whether a participating lender provides a high level of service or meets promises and commitments made to previous customers. Again, if you’re going to go loan shopping on the Internet, examine each site to see how it claims to review listed lenders. One site we’re familiar with claims to demand strict ethics from the companies it lists — no lowballing or bait-and- switch tactics — and says it has removed several dozen lenders from its list for such violations. That makes us think that the site should do a better job of screen- ing lenders upfront! Beware simplistic affordability calculators Be highly skeptical of information about the mortgage amount that you can afford. Most online mortgage calculators simplistically use overall income figures and the

- 18. current loan interest rate to calculate the mortgage amount a borrower can “afford.” These calculators are really spitting out the maximum a bank will lend you based on your income. As we discuss in Chapter 1, this figure has nothing to do with the amount you can really afford. Such a simplistic calculation ignores your larger financial picture: how much (or little) you have put away for other long-term financial goals such as retirement or college educations for your children. Thus, you need to take a hard look at your budget and goals before deciding how much you can afford to spend on a home; don’t let some slick Java-based calculator make this decision for you. Don’t reveal confidential information unless . . . Suppose that you follow all our advice in this chapter, and you find your best mortgage deal online. You may find yourself solicited to apply for your mortgage online as well. However, as you gather your confidential financial documents, you may have an unsettling feeling and wonder just how safe and wise it is to be entering this type of information into an Internet site. Griswold, R. S., Tyson, E., & Tyson, E. (2017). Mortgage management for dummies. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com Created from apus on 2020-05-04 20:26:39.

- 20. ed . A ll rig ht s re se rv ed . 134 PART 3 Landing a Lender We applaud your instincts and concerns! Here’s what you should do to protect yourself: » Do your homework on the business. In Chapter 7, we suggest a variety of questions to ask and issues to clarify before deciding to do business with any lender — online or offline. » Review the lender’s security and confidentiality policies. On reputable lender websites, you’ll be able to find the lender’s policies regarding how it handles the personal and financial information you may share

- 21. with it. We recommend doing business only with sites that don’t sell or share your information with any outside organization other than for the sole purpose of verifying your creditworthiness needed for loan approval. Be sure to choose secure sites that prevent computer hackers from obtaining the information you enter. If you’re simply not comfortable — for whatever reason — applying for a loan online, know that most online mortgage brokers and lenders offer users the abil- ity to apply for their loan offline (at an office or via loan papers sent through the regular mail). They may charge a slightly higher fee for this service, but if it makes you feel more comfortable, consider it money well spent. Be sure to shop offline You may find your best mortgage deal online. However, you won’t know it’s the best unless and until you’ve done sufficient shopping offline as well. Why shop offline? You want to be able to see all your options and find the best one. Online mortgage options aren’t necessarily the cheapest or the best. What good is a quote for a low mortgage rate that a lender doesn’t deliver on or that you won’t qualify for because of your specific property, location, or financial situation? Remember: Personal service and honoring commitments is highly important.

- 22. You may be able to save a small amount of money by taking a mortgage you find online. Some online mortgage brokers are willing to take a somewhat smaller slice of commission for themselves if they feel they’re saving time and money process- ing your loan via an online application. As we discuss in Chapter 7, mortgage brokers’ fees do vary and are negotiable. Some online mortgage brokers are will- ing to take less than the industry standard cut (1-plus percent). But just because you’ve been offered a slightly better rate online, you shouldn’t necessarily jump on it. Local lender or mortgage brokers may negotiate with you to make themselves competitive. However, you have to give them the opportunity to do so. Other things being equal, go back to the runner-up on price and give Griswold, R. S., Tyson, E., & Tyson, E. (2017). Mortgage management for dummies. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com Created from apus on 2020-05-04 20:26:39. C op yr ig ht © 2

- 24. se rv ed . CHAPTER 8 Searching for Mortgage Information Online 135 them a chance to meet or beat your best offer. You may be pleasantly surprised with the results. Mortgage websites and apps are best used to research the current marketplace rather than to actually apply for and secure a mortgage. The reason: Mortgage lending is still largely a locally driven and relationship-based business that varies based on nuances of a local real estate market. Beware of paid advertising masquerading as directories Some sites on the Internet and apps offer “directories” of mortgage lenders. Most sites charge lenders a fee to be listed or to gain a more visible listing. And, just as with any business buying a yellow pages listing or Google ad, higher visibility ads cost more. Here’s how one online directory lured lenders to advertise on its site: Sure, our basic listing is free, but we have thousands of

- 25. mortgage companies in our directory. A free listing is something like a five-second radio advertisement at 2:00 a.m. on an early Sunday morning. To make your listing really work for you, you must upgrade your listing. Upgrade, here, is a code word for pay for it! For example, a “gold listing” on this site costs $600 per year for one state and $360 for each additional state. What does that amount of money get the lender? A Gold Listing sorts your company name to the top of all listings. In addition, the Gold Listings receive a higher typeface font and a Gold Listing icon next to their name. Then there is the “diamond listing,” the “platinum listing,” the “titanium list- ing,” and you get the idea. On another directory site, you can find a “directory enhancement program,” which for $125 per year enabled a lender to buy a boldface listing and for $225 per line per year place descriptive text under the listing. Thus, prospective borrowers visiting these sites are looking at the mortgage equivalent of an online Yellow Pages advertising directory rather than a comprehensive or low- cost lender directory. If you’re considering using an Internet site or app to shop for a

- 26. mortgage, first investigate the way the site derived the list of lenders. If the site isn’t upfront about disclosing this information, be suspicious. Do some sleuthing like we did; click on the buttons at the site that solicit lenders to join the fray. Here you can Griswold, R. S., Tyson, E., & Tyson, E. (2017). Mortgage management for dummies. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com Created from apus on 2020-05-04 20:26:39. C op yr ig ht © 2 01 7. J oh n W ile y &

- 27. S on s, In co rp or at ed . A ll rig ht s re se rv ed . 136 PART 3 Landing a Lender find out how the site attracts lenders and you may also find the amount lenders

- 28. are paying to be listed. Perusing Our Recommended Mortgage Websites In addition to seeking only the highest-quality sources for you, dear reader, we don’t want you wasting your time on a wild goose chase for some unreliable website or app that’s here today and gone tomorrow. In this section, we recom- mend a short list of our favorite mortgage sites. Yes, many more sites and apps are out there, but we don’t want to bore you with a huge laundry list of mortgage- related sites. And, please remember as we discuss in Chapter 7, mortgages are distributed through numerous types of mortgage lenders and brokers. The Inter- net and the app craze are just simply another way that these players can reach prospective customers. Useful government sites Various government agencies provide assistance to low-income homebuyers as well as veterans. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s web- site (see Figure 8-1) at www.hud.gov provides information on the federal govern- ment’s FHA loan program as well as links to listings of HUD and other government agency–listed homes for sale (foreclosed homes for which the owners had FHA loans; see https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/topics/homes_for_

- 29. sale). On this site, you can also find links to other useful federal government housing–related websites. Also, if you’re a veteran, check out the VA’s website (see Figure 8-2; www. benefits.va.gov/homeloans) operated by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. In addition to information on VA loans, veterans and nonveterans alike are eligible to buy foreclosed properties on which there was a VA loan (see the website http://listings.vrmco.com). The Federal Citizen Information Center (www.pueblo.gsa.gov/housing.htm) offers numerous free and low-cost pamphlets on home financing topics such as securing home equity loans, avoiding loan fraud, finding mortgages and home improvement loans to make your home more energy efficient, and qualifying for a low down payment mortgage. You also want to know the required lender disclo- sures so you know what the lender must tell you and what it means. Griswold, R. S., Tyson, E., & Tyson, E. (2017). Mortgage management for dummies. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com Created from apus on 2020-05-04 20:26:39. C op yr

- 31. rig ht s re se rv ed . http://www.hud.gov https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/topics/homes_for_sa le https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/topics/homes_for_sa le http://www.benefits.va.gov/homeloans http://www.benefits.va.gov/homeloans http://listings.vrmco.com http://www.pueblo.gsa.gov/housing.htm CHAPTER 8 Searching for Mortgage Information Online 137 FIGURE 8-1: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Develop- ment website

- 32. provides information on FHA loan programs and HUD homes for sale. Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development FIGURE 8-2: Visit the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website for information on VA loans. Source: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Griswold, R. S., Tyson, E., & Tyson, E. (2017). Mortgage management for dummies. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com Created from apus on 2020-05-04 20:26:39. C op yr ig ht ©

- 34. re se rv ed . 138 PART 3 Landing a Lender Fannie Mae (www.fanniemae.com) has many resources for mortgage borrowers and homebuyers. In addition to helping you find mortgage lenders for home pur- chases, improvements, or refinances, the site can also turn you onto helpful worksheets and counseling agencies. Freddie Mac (www.freddiemac.com) offers similar (although not as extensive) resources. Finally, if you’re trying to fix your problematic credit report, don’t waste your money on so-called credit-repair firms, which often overpromise — and charge big fees for doing things that you can do yourself. In addition to following our credit-fixing advice in Chapters 2 and 3, also check out the Federal Trade Com- mission’s website (www.ftc.gov) for helpful credit-repair and other relevant advice regarding borrowing. Mortgage information and shopping sites

- 35. HSH Associates (www.hsh.com) is the nation’s largest collector and publisher of mortgage information. If you’re a data junkie, you’ll enjoy perusing the HSH site, which includes up-to-date mortgage rates and graphs showing recent trends (see Figure 8-3). Some lenders do choose to advertise online at HSH’s website and you can obtain their rates through the website’s ad links. FIGURE 8-3: The website of HSH Associates, publisher of mortgage information. Source: HSH Associates Griswold, R. S., Tyson, E., & Tyson, E. (2017). Mortgage management for dummies. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com Created from apus on 2020-05-04 20:26:39. C op yr ig ht ©

- 37. re se rv ed . http://www.fanniemae.com http://www.freddiemac.com http://www.ftc.gov http://www.hsh.com CHAPTER 8 Searching for Mortgage Information Online 139 Many online mortgage brokers and lenders provide rate quotes and assist with your loan shopping. The interactive features of some sites even allow prospective borrowers to compare the total cost of loans (including points and fees) under dif- ferent scenarios (how long you keep the loan and what happens to the interest rate on adjustable-rate mortgages). Interpreting these comparisons, however, requires a solid understanding of mortgage lingo and pricing. Two other sites that we like are www.bankrate.com and www.realtor.com. Bank Rate’s site offers lots of information and perspectives on many types of consumer loans including mortgages. Realtor.com’s Mortgage section is more focused on

- 38. mortgages. On both sites, you can shop for specific mortgages. Griswold, R. S., Tyson, E., & Tyson, E. (2017). Mortgage management for dummies. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com Created from apus on 2020-05-04 20:26:39. C op yr ig ht © 2 01 7. J oh n W ile y & S on s, In

- 39. co rp or at ed . A ll rig ht s re se rv ed . http://www.bankrate.com http://www.realtor.com Griswold, R. S., Tyson, E., & Tyson, E. (2017). Mortgage management for dummies. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com Created from apus on 2020-05-04 20:26:39. C op

- 41. ll rig ht s re se rv ed . 2015 V43 4: pp. 993–1034 DOI: 10.1111/1540-6229.12105 REAL ESTATE ECONOMICS A Tale of Two Tensions: Balancing Access to Credit and Credit Risk in Mortgage Underwriting Marsha J. Courchane,* Leonard C. Kiefer** and Peter M. Zorn*** Over the years 2000–2007, mortgage market underwriting conditions eased in response to public policy demands for increased homeownership. This eas- ing of acceptable credit risk in order to accommodate increased access to

- 42. credit, when coupled with the unanticipated house price declines during the Great Recession, resulted in substantial increases in delinquencies and fore- closures. The response to this mortgage market crisis led to myriad changes in the industry, including tightened underwriting standards and new market regu- lations. The result is a growing concern that credit standards are now too tight, restricting the recovery of the housing market. Faced with this history, policy an- alysts, regulators and industry participants have been forced to consider how best to balance the tension inherent in managing mortgage credit risk without unduly restricting access to credit. Our research is unique in providing explicit consideration of this trade-off in the context of mortgage underwriting. Using recent mortgage market data, we explore whether modern automated under- writing systems (AUS) can be used to extend credit to borrowers responsibly, with a particular focus on target populations that include minorities and those with low and moderate incomes. We find that modern AUS do offer a potentially valuable tool for balancing the tensions of extending credit at acceptable risks, either by using scorecards that mix through-the-cycle and stress scorecard ap- proaches or by adjusting the cutpoint—more relaxed cutpoints allow for higher levels of default while providing more access, tighter cutpoints accept fewer

- 43. borrowers while allowing less credit risk. Introduction U.S. residential mortgage markets changed dramatically during the past sev- eral years. In the early 2000s, public policy focused on expanding credit access and homeownership and specifically targeted a reduction in the home- ownership gap between minority and non-minority households and between *Charles River Associates or [email protected] **Freddie Mac or [email protected] ***Freddie Mac or [email protected] C© 2015 American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association 994 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn higher and lower income families.1 Relaxation of underwriting standards, ac- companied by a surge in subprime lending and an attendant proliferation of new products, resulted in many borrowers who could not meet traditional un- derwriting standards being able to obtain home mortgages and achieve home ownership. However, the environment changed with the mortgage market crisis of 2007 and 2008 when the subprime sector collapsed nearly entirely

- 44. and delinquency and foreclosure rates increased throughout the country. In response, underwrit- ing standards tightened and legislation was passed imposing more stringent regulations on the mortgage industry, particularly the Dodd- Frank Act reg- ulations, which introduced both Qualified Mortgage (“QM”) and Qualified Residential Mortgage (“QRM”) standards. While providing assurance that the performance of recent mortgage originations will reduce the likelihood of another housing crisis, this tightening of standards comes at a significant cost in terms of access to credit. Balancing the tension between access to credit and the management of credit risk remains an ongoing concern. The rich history of mortgage performance data over this period offers an opportunity to better distinguish mortgage programs and combinations of borrower and loan characteristics that perform well in stressful economic en- vironments from those that do not. The relaxed underwriting standards of the 2000s provide plentiful performance information on borrowers who stretched for credit, but then experienced the stressful post-origination environment of declining house prices and rising unemployment. While many of these loans performed poorly, a large number performed well. Our goal is to identify the characteristics that distinguish between these two groups.

- 45. We specifically examine whether the recent data can be used to create a mod- ern automated underwriting scorecard that effectively and responsibly extends mortgage credit to the general population, and to underserved or targeted bor- rowers who reside in low-income communities, make low down payments and have poorer credit histories. Our analysis focuses on mortgage under- writing, rather than mortgage pricing. This reflects the two- stage approach to mortgage lending broadly practiced in the United States— originators first underwrite applications to determine whether they qualify for origination, and then price the loans that are originated successfully. 1For example, former United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Secretary Mel Martinez states in 2002 that “The Bush Administration is committed to increasing the number of Americans, particularly minorities, who own their own homes.” A Tale of Two Tensions 995 There are four steps necessary to complete this exercise. First, we empirically estimate a mortgage delinquency model. Second, we convert the estimated delinquency model to an underwriting scorecard for assessing

- 46. risk, where higher scores signify higher risk. Third, we determine a scorecard value (a “cutpoint” or risk threshold) that demarcates the marginal risk tolerance— score values equal to or below the cutpoint are viewed as acceptable risk; score values above the cutpoint are not. Fourth, we process borrowers through this prototype of an automated underwriting system. We then determine the proportion of the population of mortgage applicants that is within acceptable risk tolerances, and the historic performance of these “acceptable” loans. The main data we use for this analysis are loan-level observations from CoreLogic on mortgages originated in the conventional (prime and subprime) and government sectors from 1999 through 2009. For each of the three market sectors, we separately estimate the probability that borrowers will become 90-days or more delinquent on their loans within the first three years after origination. Included in the model are standard controls for borrower and loan characteristics, as well as for key macroeconomic factors affecting mortgage performance post-origination (specifically, changes in house prices, interest rates and unemployment rates). Underwriting scorecards provide ex ante assessments of mortgage risk at

- 47. origination, so creating scorecards requires appropriate treatment of the post-origination variables in our estimated models. Two broad approaches are possible. One approach attempts to forecast post-origination variables across borrower locations and over time. The other approach sets post- origination variables to constant values for all borrowers and all time periods. We use the latter approach. Specifically, we create two separate scorecards. The first scorecard sets post-origination values of house prices, interest rates and un- employment rates to their constant long run average levels (a “through-the- cycle” scorecard). The through-the-cycle scorecard is inherently “optimistic” with respect to credit risk, and therefore reflects a focus on access to credit. The second scorecard sets post-origination values of house prices, interest rates and unemployment rates to the varying ex post values defined by the Federal Reserve in an adverse scenario (a “stress” scorecard) as defined in the 2014 supervisory stress test for very large banking organizations.2 The stress scorecard focuses on “tail” events that are unlikely to occur and is meant to prevent crisis outcomes such as those observed during the Great Recession. This scorecard therefore represents a focus on credit risk management. 2See http://www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/stress-

- 48. tests/2014-appendix-a.htm. 996 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn The next challenge requires choosing appropriate scorecard cutpoints for delimiting loans within acceptable risk tolerances. This, in combination with the choice of scorecard, is where much of the tension between credit access and credit risk resides. Higher cutpoints provide greater access at the cost of increasing credit risk; lower cutpoints limit credit risk but restrict access. As the choice of a cutpoint is a complicated policy/business decision, we provide results for a variety of possible cutpoints, ranging from a low of a 5% delinquency rate to a high of a 20% delinquency rate. In an effort to put forward a possible compromise between access and credit risk, we explore in more detail results for alternative cutpoints that are market- segment-specific; 5% for prime loans, 15% for subprime loans and 10% for government loans. We argue that these values represent reasonable risk tolerances by approxi- mating the observed delinquency rates in these segments between 1999 and 2001. The combination of scorecards and cutpoints creates working

- 49. facsimiles of modern AUS, and we apply these systems to both the full and target pop- ulations.3 For this exercise, our “target” population is defined as borrowers with loan-to-value (“LTV”) ratios of 90% or above, with FICO scores of 720 or below or missing, and who are located in census tracts with median in- comes below 80% of area median income. This group is generally reflective of “underserved” borrowers for whom there is particular policy concern. We find that automated underwriting, with a judicious combination of score- card and cutpoint choice, offers a potentially valuable tool for balancing the tensions of extending credit at acceptable risks. One approach entails using scorecards that mix the through-the-cycle and stress scorecard approaches to post-origination values of key economic variables. Moving closer to a through-the-cycle scorecard provides more focus on access to credit. Moving closer to a stress scorecard provides more focus on the control of risk. The second approach is to adjust the cutpoint—more relaxed cutpoints allow for higher levels of default while providing more access, tighter cutpoints have accept fewer borrowers while allowing less credit risk. Previous Literature

- 50. A considerable body of research has examined outcomes from the mortgage market crisis during the past decade. Of particular relevance for this research 3We weight the data using weights based on the proportion of the target population in the Home Mortgage Disclosure data (“HMDA”) to ensure that the target population in our data is representative of the target population in HMDA. This allows us to draw inferences to the full population. A Tale of Two Tensions 997 are studies that examine specific underwriting standards and products that may be intended for different segments of the population, or that address the balancing of access to credit and credit risk. A recent paper by Quercia, Ding, and Reid (2012) specifically addresses the balancing of credit risk and mortgage access for borrowers—the two tensions on which we focus. Their paper narrowly focuses on the marginal impacts of setting QRM product standards more stringently than those for QM.4 They find that the benefits of reduced foreclosures resulting from the more stringent product restrictions on “LTV” ratios, debt-to-income ratios (“DTI”) and credit scores do not necessarily outweigh the costs of reducing

- 51. borrowers’ access to mortgages, as borrowers are excluded from the market. Pennington-Cross and Ho (2010) examine the performance of hybrid and ad- justable rate mortgages (ARMs). After controlling for borrower and location characteristics, they find that high default risk borrowers do self-select into adjustable rate loans and that the type of loan product can have dramatic im- pacts on the performance of mortgages. They find that interest rate increases over 2005–2006 led to large payment shocks and with house prices declin- ing rapidly by 2008, only borrowers with excellent credit history and large amounts of equity and wealth could refinance. Amromin and Paulson (2009) find that while characteristics such as LTV, FICO score and interest rate at origination are important predictors of defaults for both prime and subprime loans, defaults are principally explained by house price declines, and more pessimistic contemporaneous assumptions about house prices would not have significantly improved forecasts of defaults. Courchane and Zorn (2012) look at changing supply-side underwriting stan- dards over time, and their impact on access to credit for target populations of borrowers.5 They use data from 2004 through 2009, specifically focusing

- 52. on the access to and pricing of mortgages originated for African-American and Hispanic borrowers, and for borrowers living in low-income and minor- ity communities. They find that access to mortgage credit increased between 2004 and 2006 for targeted borrowers, and declined dramatically thereafter. The decline in access to credit was driven primarily by the improving credit mix of mortgage applicants and secondarily by tighter underwriting standards 4For details of the QRM, see Federal Housing Finance Agency, Mortgage Market Note 11-02. For details of the QM, see http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201310_cfpb_qm- guide-for-lenders.pdf. 5See also Courchane and Zorn (2011, 2014) and Courchane, Dorolia and Zorn (2014). 998 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn associated with the replacement of subprime by FHA as the dominant mode of subprime originations. These studies all highlight the inherent tension between access to mortgage credit and credit risk. They also stress the difficulty in finding the “cor- rect” balance between the two, and suggest the critical importance of treat- ing separately the three mortgage market segments—prime,

- 53. subprime and government-insured (FHA)—because of the different borrowers they serve and their differing market interactions. The research also provides some op- timism that a careful examination of recent lending patterns will reveal op- portunities for responsibly extending credit while balancing attendant credit risks. Data Our analysis uses CoreLogic data for mortgages originated between 1999 and 2009. The CoreLogic data identify prime (including Alt-A), subprime and government loans serviced by many of the large, national mortgage servicers. These loan-level data include information on borrower and loan product characteristics at the time of origination, as well as monthly updates on loan performance through 2012:Q3. Merged to these data are annual house price appreciation rates at a ZIP code level from the Freddie Mac Weighted Repeat Sales House Price Index, which allow us to update borrower home equity over time.6 We prefer this house price index to the FHFA’s, as the latter are not available at the ZIP code level. The CoreLogic data do not provide Census tract information, so we use a crosswalk from ZIP codes to 2000 Census tracts.7 We also merge in county-level

- 54. unemployment rates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which are seasonally adjusted by Moody’s Analytics.8 Finally, we include changes in the conventional mortgage market’s average 30-year fixed mortgage (“FRM”) rate reported in Freddie Mac’s Primary Mortgage Market Survey.9 The CoreLogic data are not created through a random sampling process and so are not necessarily representative of the overall population, or our target 6While these data are not publicly available, the metro/state indices can be found which are available at: http://www.freddiemac.com/finance/fmhpi/. 7Missouri Census Data Center, available at: http://mcdc.missouri.edu/ websas/geocorr12.html. 8The unemployment rate is from the BLS Local Area Unemployment Statistics (http://www.bls.gov/lau/). 9These data are available publicly at: http://www.freddiemac.com/pmms/pmms30.htm. A Tale of Two Tensions 999 population. This is not a problem for estimating our delinquency model, but it does create concern for drawing inference with our scorecards. To address this potential concern, we apply appropriate postsample weights

- 55. based on HMDA data to enhance the representativeness of our sample. We develop weights by dividing both the HMDA and the CoreLogic data into categories, and then weight so that the distribution of CoreLogic loans across the categories is the same as that for HMDA loans. The categories used for the weighting are a function of loan purpose (purchase or refinance), state, year of origination and loan amount. Because we rely on a postsample approach and cannot create categories that precisely define our target population, our weighting does not ensure representativeness of the CoreLogic data for this group. Nevertheless, it likely offers a significant improvement over not weighting. We also construct a holdout sample from our data to use for inference. This ensures that our estimated models are not overfitted. The holdout sample was constructed by taking a random (unweighted) sample of 20% of all loans in our database. All summary statistics and estimation results (Tables 1 and 2 and Appendix) are reported based on the unweighted 80% estimation sample. Consistent with our focus on identifying responsible credit opportunities, we restrict our analysis to first lien, purchase money mortgage loans. Summary statistics for the continuous variables used in our delinquency estimation are found in Table 1. Table 2 contains summary statistics for the

- 56. categorical variables. As shown in Table 1, the average LTV at origination is 97% for government loans. This is considerably higher than for the prime market, where first lien loans have LTVs less than 80%, on average.10 We also observe the expected differences in FICO scores, with an average FICO score in the prime sector of 730, 635 for subprime and 674 for government loans. The prime market loan amount (i.e., unpaid principal balance, or UPB, at origination) averages $209,000 with the government loan amount the lowest at a mean of $152,000. The mean value in the subprime population is below that for prime at $180,000. DTI ratios do not differ much between prime and government loans, and the DTI for subprime is unavailable in the data. As DTI is a key focus in the efforts of legislators to tighten underwriting standards, we use it when available for estimation. The equity measures post- origination reflects the LTV on the property as house prices change in the area. All three markets faced significant house price declines, as captured by the change in home equity one, two or three years after origination. For all three 10The mean LTV for subprime mortgages is surprisingly low at 83%, although this

- 57. likely reflects the absence of recording second lien loans, which would lead to a higher combined LTV. 1000 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn T ab le 1 � S um m ar y st at is ti cs fo r co nt

- 81. .5 0% 29 .0 5% 34 .6 4% 21 .8 4% A Tale of Two Tensions 1001 T ab le 1 � C on ti nu ed

- 99. % 2. 72 % 1002 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn Table 2 � Summary statistics for categorical (class) variables (80% estimation sample)—statistics not weighted. All Prime Subprime Government ARM 12.60% 48.50% 4.72% 14.91% Balloon 0.39% 4.91% 0.05% 0.82% FRM-15 7.68% 1.61% 1.16% 5.63% FRM-30 68.25% 22.31% 90.14% 67.79% FRM-Other 4.48% 1.71% 2.73% 3.81% Hybrid 6.59% 20.97% 1.20% 7.04% Other 41.05% 33.13% 43.57% 40.71% Retail 33.70% 21.20% 22.12% 29.87% Wholesale 25.25% 45.67% 34.31% 29.42% Full Documentation 29.83% 49.38% 41.80% 34.52% Missing 38.89% 18.44% 42.30% 37.35% Not Full Documentation 31.27% 32.19% 15.90% 28.13% Owner Occupied 83.43% 85.88% 91.84% 85.48% Not Owner Occupied 16.57% 14.12% 8.16% 14.52% Condo 13.82% 7.75% 6.97% 11.70% Single Family 86.18% 92.25% 93.03% 88.30% mortgage market segments, post-origination equity measures (post-origination

- 100. estimated LTV) averaged over 90%. Post-Origination unemployment rates are highest, on average, in the geographies with government loans, although the differentials among market segments fell after three-year post- origination. Table 2 presents the summary statistics for the categorical (class) variables in our sample. Some expected results emerge. The subprime segment has the largest share of loans originated through the wholesale channel at 45.7%, while the wholesale share for the prime segment was only 25.2%. Nearly half (48.5%) of subprime loans were “ARM” loans, while only 22.3% of subprime loans were the standard 30-year FRM product. In contrast, 69.1% of prime loans were 30-year FRMs and an additional 7.8% were 15-year FRMs. Nearly all of the government loans (91.2%) were 30-year FRMs. The documentation figures are somewhat surprising, with nearly half (49.4%) of subprime loans indicating full documentation. The low share of full documentation loans in the prime sector (about 30%) likely reflects the inclusion of Alt-A loans, which are defined to be prime loans in the CoreLogic data.11 In our analyses, we focus on access to credit and credit risk outcomes for all borrowers. However, many homeownership and affordable lending programs

- 101. 11Historically, Alt-A loans were originated through prime lenders, offering their more credit worthy customers a simpler origination process. A Tale of Two Tensions 1003 focus more narrowly on assessing opportunities for responsibly extending mortgage credit to borrowers with low down payments and poor credit his- tories, or who are otherwise underserved by the prime market (“target pop- ulation”). As a result of long standing public policy objectives focused on the value of homeownership, both government insured mortgage programs (such as FHA) and the GSEs have long held missions to meet the needs of underserved borrowers, including low income, minority and first-time home- buyers.12 Programs meeting this mission are tasked with balancing access to credit for borrowers with any attendant increases in credit risk. Therefore, aside from our focus on the opportunities provided to the full pop- ulation of borrowers, we also provide an analysis of scorecard outcomes for a specific target population. We define this target population as borrowers who receive first lien, purchase money mortgages on owner-occupied properties located in census tracts with median incomes below 80% of the area median

- 102. income, with FICO scores less than or equal to 720 and with LTV ratios greater than or equal to 90%. Limiting our analysis to borrowers who live in lower income census tracts is especially constraining, as many borrowers with high LTVs and lower FICO scores live elsewhere. However, our data lack accurate income measures, and public policy considerations encourage us to include an income constraint in our definition of the target population.13 As a consequence, loans to target borrowers account for a small percentage of the total loans made during our period of study (roughly 4%). We can be assured, however, that our target population is composed of borrowers who are an explicit focus of public policy. Figure 1 provides a graphical illustration of the HMDA- weighted distribution of target population loans in our sample across the three market segments. The dramatic shift over time in the share going to the government sector is obvious, as is the reduction in the number of loans originated to the target population by all three segments, combined, post-crisis. 12Both the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and the Federal Housing Enterprises Financial Safety and Soundness Act of 1992 (the 1992 GSE Act) encouraged mortgage

- 103. market participants to serve the credit needs of low- and moderate-income borrowers and areas. 13For example, GSE affordable goals are stated with respect to low- and moderate- income borrowers and neighborhoods. 1004 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn Figure 1 � Target population by year and market segment (weighted). Analysis Our analysis begins with the estimation of mortgage performance models over the crisis period. We use loan-level origination data from 1999 through 2009 to estimate models of loans becoming 90-days or more delinquent in the first three years after origination. These models include standard borrower and loan characteristics at origination, as well as control variables measuring changes in house prices, unemployment rates and interest rates post- origination. They also include several interaction terms for the borrower, loan and control variables. We then use our estimated delinquency models to specify two underwrit- ing scorecards—a through-the-cycle scorecard and a stress scorecard.14 We

- 104. next apply various cutpoints (risk thresholds) to our scorecards to define levels of acceptable risk. By definition, loans with risk scores (delinquency probabilities) at or below the cutpoint are assumed to be within appropriate (acceptable) risk tolerances. The scorecard and cutpoint combinations provide working prototypes of an AUS. Our final step applies these prototypes to the full and target populations and assesses the results. Estimating the Models We estimate three separate delinquency models based on an 80% sample of first-lien, purchase money mortgage loans in our data. Separate models 14Additional scorecards constructed using “perfect foresight” and macroeconomic forecasts are available from the authors upon request. A Tale of Two Tensions 1005 were estimated for prime loans (including Alt-A loans), subprime loans and government loans, using an indicator provided in the CoreLogic data to as- sign each loan to its appropriate segment.15 We estimate separate models for each market sector because we believe that there is clear market

- 105. segmenta- tion in mortgage lending. In the conventional market the lenders, industry practices, market dynamics and regulatory oversight have differed between the prime and subprime segments.16 A similar distinction exists between the conventional and government segments—the latter focuses on first-time bor- rowers and lower income households. Moreover, acceptable risk tolerances will necessarily vary across segments, as may concerns regarding access to credit. Our process differs from the typical construction of underwriting systems in two important ways. First, while the CoreLogic data are reasonably rich in variables, they do not contain the detailed credit variables, such as tradeline balance to limits, number of open tradelines and presence of mortgage late payments, which are a key component of most underwriting models. As a result, our model assesses risk less accurately than production versions. Second, typical models are estimated on historical data, but the resulting scorecards are applied to future applications (i.e., out of sample). However, lacking knowledge and data on future states of the world, we use historical assessments and apply our scorecard to the 20% holdout sample. Thus, our scorecard may assess risk more accurately than production

- 106. versions, given that the data were contemporaneously generated. However, we believe that this is not a critical concern because we seek to illustrate how certain scorecard and cutpoint combinations might affect outcomes under future stressful market conditions. The dependent variable in our estimation is a loan becoming 90 days or more delinquent in the first three years after origination. Continuous ex- planatory variables include borrower FICO scores, mortgage market interest rates (Freddie Mac Primary Mortgage Market Survey rates), updated LTVs (derived using the Freddie Mac House Price Index) and local unemploy- ment rates.17 The models also include categorical explanatory variables for 15Because this field is determined at CoreLogic, we are unable to define the specific parameters around the determination of subprime. 16This structural segmentation also loosely translates into separation on the basis of risk—the prime segment generally caters to lower risk borrowers, while the subprime segment generally caters to higher risk borrowers—however, the distinction along this dimension is far from perfect. We are segmenting by market structure, not simply by market risk. 17We include variables estimated to model post-origination home equity one-

- 107. year, two-year and three-year post-origination. If equity one- year post-origination 1006 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn loan amount ($50,000–$150,000, $150,000–$250,000, $250,000–$350,000, $350,000–$450,000 and greater than $450,000); documentation type (full documentation, low documentation and missing documentation); origination channel (retail, wholesale and other); original LTV (less than 40%, 40–60%, 60–75%, 75–80%, 80–85%, 85–90%, 90–95%, 95–105%, 105 to–115% and greater than 115%); product type (ARM, balloon, 15-year FRM [“FRM-15”], 30-year FRM [“FRM-30”] and other FRM and hybrids [“FRM- other”]) and condo and owner occupancy indicators. Finally, interactions were included between FICO score of borrower and whether FICO was missing, FICO score and loan amount, loan amount and LTV and FICO score and LTV.18 The estimation results, based on the 80% sample, are presented in Appendix Tables A.1.a (prime), A.2.a (subprime) and A.3.a (government). Goodness- of-fit plots, applied to the holdout sample, are found in Figures A.1.b (prime), A.2.b (subprime) and A.3.b (government). Most of the variables in the prime

- 108. delinquency model (Figure A.1) had the expected signs. Loans with LTV ratios less than 80%, full documentation loans, retail channel loans, loans under the conforming limits and FRM loans are all less likely to become delinquent. As FICO score increases, the delinquency probability falls. Loans with higher LTV values have higher delinquency rates, with the loans in the over 100 LTV categories most likely to go delinquent. Owner occupants are less likely to become delinquent. Most of the subprime results (Figure A.2.a) are similar to those in the prime model with a few exceptions. As in the prime segment, owner- occupied and FRM loans are less likely to become 90 days delinquent. LTV also has a similar relationship with delinquency in both the prime and subprime mod- els; however, the parameter estimates on the high LTV prime loans exceed those for subprime, perhaps reflecting missing second lien loans in the sub- prime population. There are some differences in the two models, however. For example, full documentation subprime loans are more likely to become is defined as ltv_1yr, then ltv_1yr = ltv*upb_1yr/[upb /( 1 + hpa_1yr_orig)] where ltv = LTV at origination, upb = upb at origination and hpa_1yr_orig = house price growth (in %) from origination to one year after

- 109. origination and upb_1yr = upb 1 year after origination, assuming no delinquency/curtailment, and a fully amortizing loan. Then, upb_1yr= upb + FINANCE(’CUMPRINC’, initial_interest_rate/1200, original_term, upb, 1, 12); where FINANCE is a SAS function used to compute the cumulative principal. See: http://support.sas.com/ documentation/cdl/en/lrdict/64316/HTML/default/viewer.htm#a 003180371.htm 18We use an indicator variable for observations with missing DTI in the prime and government segments (this is the omitted category.) DTI is missing for all subprime loans. For missing FICO, we create a variable denoted as FICO2 and set scores when missing to 700 and to actual values otherwise. We interact FICO2 with a dummy for missing status. A Tale of Two Tensions 1007 delinquent, as are loans from the retail channel. Higher FICO scores do not reduce the likelihood of subprime mortgage delinquency. For the government segment, retail channel has the negative sign we observed in prime. Nearly all government loans are full documentation, so the result carries little meaning. Finally, higher LTV and lower FICO government loans scores have an increased probability of delinquency. Owner

- 110. occupancy and the retail channel reduce the probability of delinquency, as do FRM loans. We assess model fit by comparing model predictions to actual outcomes. The results of these comparisons are provided in the Appendix as Figures A.1.b, A.2.b and A.3.b for the prime, subprime and government estimations, respectively.19 In general, we see that the models fit well. Specifically, the scatter plots remain relatively close to the 45-degree reference line. To the extent that there is any systematic error in the model, it occurs for lower risk loans (toward the bottom left of the chart). This causes relatively little concern for our analysis because it is most important that the model is well-fit in the area around likely cutpoints, which is located in the well- fitting higher risk (upper right-hand) section of the charts. Finally, in Figures 2.a (prime), 2.b (subprime) and 2.c (government), we use predictions from our estimated model on the weighted holdout sample to provide a distributional sense of loans originated throughout the years in our sample. Specifically, using our predictions, we rank order loans within each market segment and origination year into approximately 200 buckets. For each bucket of loans, we compute the realized default rate. We then generate

- 111. a box plot illustrating the distribution of average default rates over our 200 buckets by market segment and year.20 The three charts below immediately highlight the dramatic increase in delin- quency rates that occurred during the crisis years of 2005–2008. Clearly, 19Loans in each segment are first grouped by model prediction, and then divided into 200 equally sized buckets of loans with similar model predictions. The mean model prediction and actual delinquency rates are calculated for each bucket, and then plotted in log-log scale. The model prediction is measured on the horizontal axis, and the actual delinquency rate is measured on the vertical axis. A 45- degree reference line is drawn in each chart, reflecting the combination of points where the models are perfectly predicting. 20The “box” in the box plot shows the interquartile range (“IQR”)—the scores between the 25th and the 75th percentiles. The “whiskers” go down to the 5th percentile, and up to the 95th percentile of scores. The 50th percentile (the median) falls within the box. The data are weighted via HMDA to more accurately reflect the underlying population. 1008 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn

- 112. Figure 2 � a. Prime, b. Subprime and c. Government. there is justification for a general concern over credit risk and the perfor- mance of loans under stressful conditions in particular. It is also interesting to compare the relative performance of loans across the market segments. In the years 1999–2004, prime loans were clearly the best performing, followed by government loans, and then subprime. However, the government segment performed roughly as well as the prime segment during the crisis years. This is because Alt-A mortgages are primarily allocated to the prime segment (as they were primarily originated by prime lenders) and these loans performed very poorly. Regardless, both the prime and government segments look much A Tale of Two Tensions 1009 better than subprime during the crisis years—as subprime delinquency rates reached an average of 40% for 2006 and 2007 originations. Deriving the Scorecards The second step of our analysis is to derive prime, subprime and government scorecards from the estimated models. Scorecards are an ex ante assessment of the credit risk at origination associated with a particular

- 113. borrower/loan combination. Our estimated delinquency models provide the basis for this assessment; although these models include both ex ante and ex post (post- origination) explanatory variables. The appropriate treatment of the post- origination explanatory variables is the key challenge for scorecard creation. One approach, arguably the most typical, is to treat post- origination explana- tory variables as controls in the scorecard.21 That is, to keep the value of these variables constant across borrowers and over time. This is the approach we use here, although we create two variants. The first version we call a “through- the-cycle” scorecard. For this scorecard, we set post-origination variables to approximately their long run averages (house prices are set at a 2% annual increase, interest rates are assumed to remain unchanged after origination and unemployment rates are set at 6%). This provides a generally “friendly” view of credit risk, and so is reflective of a concern for access to credit is- sues. The through-the-cycle scorecard also has the policy advantage of being countercyclical. We also create a second version that we call our “stress” scorecard. For this scorecard, we incorporate the values of the ex post explanatory variables used

- 114. by the Federal Reserve Board in its 2014 severely adverse stress test scenario. The Federal Reserve’s provides paths under the severely adverse scenario for several macroeconomic variables, including unemployment, house prices and mortgage rates. This represents a hypothetical scenario containing both reces- sion and financial market stress aimed to assess the resiliency of U.S. financial institutions. In this regard, our scorecard represents an outer- bound possibility of risk, and is clearly reflective of a concern for credit risk. For each loan scored under the stress scorecard, we use cumulative house price declines of 12.4%, 24.2% and 24.7 for one-year, two-year and three-year post-origination, respectively, to update our equity variable in the stress scorecard. We expect the stress scorecard to be very tight with respect to access, which should limit its risk exposure during downturns. Separate scorecards are created for each 21An alternative approach is to forecast at origination the future values of the ex post explanatory variables. This is a challenging task in both theory and prac- tice. A prototype version of such a scorecard is available from the authors on request. 1010 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn

- 115. of the models/markets: prime, subprime and government. We believe that it is enlightening to compare and contrast the results of the through-the-cycle and stress scorecards for each market. While we expect the through-the-cycle scorecard to lead to increased access to credit relative to the stress scorecard, it may achieve this at the cost of higher credit risk. We expect, for example, that it will perform significantly worse than the stress scorecard during down cycles. Choice of Cutpoints The third step in our analysis is to choose scorecard cutpoints. The cutpoints set the marginal risk tolerance for the scorecards, and so determine the lev- els at which loans switch from “acceptable” to “unacceptable” risks. The cutpoints therefore set the extreme bounds of within-tolerance risk for the scorecards, and are critical in setting the balance between access to credit and credit risk concerns. Both policy and business considerations influence the determination of cut- points. For example, a 10% delinquency rate might be viewed as an acceptable prime cutpoint during boom years when the market is optimistic and public policy is focused on expanding access to credit. However, that same 10%

- 116. delinquency rate might be viewed as too high for a prime cutpoint during a recession, when the market is trying to limit credit exposure and public policy has shifted its focus to managing systemic risks and taxpayer losses. Lenders with more tolerance for risk might choose to operate in the subprime market segment, and will accept higher risk thresholds than lenders who want to operate in the prime segment. Government-insured risk tolerance levels may vary with the health of the mortgage insurance fund, as well as other policy considerations. It is not our intention to propose “correct” cutpoints for our scorecards. Rather, our goal is to illustrate how the interactions between scorecards and possible cutpoints affect access to credit and the management of credit risk, and to illustrate the potential for possible compromises. Toward this end, we provide a set of potential cutpoints for each scorecard. Specifically, we provide results for cutpoints of 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% delinquency rates for each of our scorecards. This allows us to provide a range of alternative impacts on both the full and target populations. To simplify our presentation and focus our analysis, we also concentrate on a select cutpoint for each market that offers a possible compromise between

- 117. managing access and credit risk. This is determined by choosing among our four cutpoints for each market the one that most closely approximates the A Tale of Two Tensions 1011 actual delinquency rate of marginal loans originated in the years 1999–2001. These years provide origination cohorts that experienced a relatively benign economic environment for the first three years after origination (neither ex- pansive nor depressed), and their realized performance is not unduly affected by factors outside the control of underwriting. Underwriting in the prime market during the 1999 –2001 period was rela- tively standardized (arguably, neither too loose nor too tight), so we set the select cutpoint at the realized performance of borrowers around the 90th risk percentile from the full model prediction. This performance is most closely approximated by a cutpoint of 5% delinquency rates for the prime market (see Figure 2.a), and by construction this results in about 90% of the prime loans originated in 1999–2001 being viewed as acceptable risk.22 The subprime performance distribution (see Figure 2.b) displays a markedly

- 118. different time trend than that observed in the prime market. Realized per- formance in the years 1999–2001 was worse than the performance of the 2002–2004 cohorts. This suggests that subprime underwriting in the earlier period was not as standardized as it was in the prime market during those years. Moreover, the differential in risk between prime and subprime lending appears greater in the earlier years, suggesting that subprime lending was relatively less conservative than prime lending in 1999–2001. Finally, the overall tolerance for accepting risk in mortgage lending has clearly declined in the recent environment. These factors persuade us to use a more restrictive standard for determining marginal borrows in the subprime segment than we do in the prime segment. For the subprime market, we choose a cutpoint of a 15% delinquency rate, which results in only about one-half of the subprime loans originated in in 1999–2001 being viewed as acceptable risk in terms of their realized outcomes. The performance distribution of government-insured loans is shown in Figure 2.c. As with the subprime market, the box plots for government mort- gage lending suggest that underwriting was not as standardized or (relatively) conservative as in the prime market from 1999 to 2002. Particularly, striking

- 119. is the more limited relative increase in the risk distributions of the 2006–2008 originations than the increase experienced by these cohorts in the subprime market. We therefore again impose a more restrictive standard for determining the marginal borrowers in the government market, but mitigate this somewhat because of the government sector’s explicit goal of providing credit to first 22The 90th risk percentile is the scorecard prediction level that separates the 10% of borrowers with the highest predicted risks from the remaining 90% of borrowers with lower predicted risks. 1012 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn time and traditionally underserved home buyers. This yields a select cutpoint for the government sector of a 10% delinquency rate, which results in about 60% of the 1999–2001 cohort being viewed as acceptable risk in terms of their realized outcomes. Applying Scorecards to the Full and Target Populations Our last step applies our automated underwriting scorecards to the full and tar- get populations. As noted earlier, the target population represents only about 4% of overall originations during our period of study. Although

- 120. a restrictive definition, we believe that our resulting target population is highly reflective of the population focused on by most affordable housing initiatives. We use our through-the-cycle and stress scorecards to separately score borrowers, and then determine the percent of the population assessed as acceptable risks by each scorecard using the alternative cutpoints (expressing risk thresholds of 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% delinquency rates). Table 3.a presents the results for the full population, while Table A.4a, in the Appendix, presents the results for the target population. Table 3.b presents the share of defaults for the full population for each scorecard in each risk threshold range. Table A.4b in the Appendix provides similar values for the target population. As indicated in Table 3.a, using a cutpoint of 5%, we find that 85.1% of all prime borrowers are viewed as acceptable risks by the through-the-cycle scorecard over 1999–2009, while the stress scorecard yields only 60.8 accept- able risks among prime borrowers. If the risk threshold is relaxed to a level of 10%, 97.6% of the prime market borrowers are acceptable risk. Over time, at a 5% prime cutpoint, the percent of acceptable risks falls as the origina- tion population reflects the historic relaxation of underwriting standards—the market includes more high risk borrowers, so a lower percent

- 121. are accepted with the 5% cutpoint. For the subprime market segment, the through-the-cycle scorecard assesses 39.7% as acceptable risk with a default risk threshold set at 15%, while only 4.7% are acceptable using the stress scorecard. If the risk threshold is held to 5%, only 2.5% are accepts. Finally, in the government segment, using a 10% threshold, 61.1% of bor- rowers are acceptable risks with the through-the-cycle scorecard. At a 5% threshold, only 4.7% would have been able to receive mortgages. As expected, the through-the-cycle scorecard accepts more borrowers than does the stress scorecard during a stressful environment, with the differ- ential impacts of the two scorecards varying by market segment. The prime A Tale of Two Tensions 1013 T ab le 3. a

- 145. 7 3. 3 3. 2 4. 3 3. 8 4. 7 4. 0 2. 3 2. 5 2. 9 1014 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn T ab

- 168. 31 .8 25 .0 17 .0 14 .8 19 .8 A Tale of Two Tensions 1015 T ab le 3. b � S ha re of to

- 192. .5 8. 0 11 .3 1016 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn T ab le 3. b � C on ti nu ed . S co re ca

- 214. .3 36 .9 35 .1 36 .2 42 .1 43 .5 37 .0 28 .8 24 .8 33 .2 A Tale of Two Tensions 1017 market, even with a lower risk threshold (5% cutpoint), accepts a significantly

- 215. higher percentage of borrowers using either scorecard. The stress scorecard, because of its very pessimistic view of post-origination outcomes, completely eliminates access to credit in the subprime segment, and nearly eliminates the possibility of acceptable credit risks in the government segment. Table A.4.a, as shown in the Appendix, provides results for acceptable risks among target borrowers. Using our select set of cutpoints, we find that 55.1% of the prime targeted borrowers are viewed as acceptable risks by the through- the-cycle scorecard. The stress scorecard yields 12.8%. For the subprime market, these values are 24.9% and 0.2%, respectively, and for the government market, they are 54.3% and 5.2%, respectively. All of the borrowers in the full population received loans under the standards present at the time of origination. Applying a modern version of a through-the- cycle or stress scorecard, many of those borrowers would have failed to qualify for a loan. This suggests that AUS also offer some potential for responsibly extending credit to the target population. However, the through- the-cycle and stress scorecards offer competing policy trade-offs. The through-the-cycle scorecard extends credit to a larger percentage of the target population by providing greater access during expansionary cycles. The stress scorecard

- 216. severely restricts access during periods of financial stress, as designed. Table 3.b provides the share of defaults by risk threshold. In the prime mar- ket, at a 5% cutpoint, 85.1% of the borrowers are accepted but this group is responsible for only 55.9% of the defaults. In contrast, at a 15% subprime cutpoint, the through-the-cycle scorecard accepted 39.7% of borrowers rep- resenting 26.3 of defaults. Finally, in the government segment, while 61.1% were acceptable at a 10% cutpoint, that group’s share of defaults was 44.6%. Only the prime market is of interest when assessing the default share by cutpoint using the stress scorecard for the full population (Table 3.b). The stress scorecard accepted 60.8% using the 5% cutpoint and this resulted in loans that comprised 25.5% of the total defaults in the population. For the target population (Table A.4.b), the share of defaults for target borrowers in the prime segment is 35.1% with a 5% cutpoint; while it is 17.5% for subprime with a 15% cutpoint and 45.7% for government with a 10% cutpoint. In every case, the percent of acceptable risks outweighs the default share. In summary, acceptable levels of risk can be achieved in two ways. Either the scorecard can reflect a more stressful environment post-

- 217. origination, which means that the post-origination values of the macroeconomic variables are more pessimistic relative to the through-the-cycle scorecard, or the cutpoints 1018 Courchane, Kiefer and Zorn can be adjusted. For example, in examining the results for the prime scorecard, 85.1% of the full population posed acceptable risks using the through-the- cycle scorecard using a 5% cutpoint. That dropped to 60.8% using the stress scorecard. Approximately the same percentage of prime mortgages (88.0%) could be accepted using the stress scorecard, but that requires relaxing the cutpoint to 10%. It is similarly likely that using the through- the-cycle score- card and tightening the cutpoints would lower the percent of acceptable risks in a manner similar to the application of the stress scorecard. It is clear that using both levers to manage credit risk (a stress scorecard and tight cutpoints) virtually eliminates credit access in the subprime and the government market segments. For example, a 15% cutpoint and a stress scorecard in the subprime segment results in only 4.7% of the full popula- tion being approved for loans. Using the stress scorecard in the government

- 218. segment, with a cutpoint 10%, means that only 10.3% of borrowers are ac- ceptable credit risks. For the target population borrowers, using the stress scorecard and tighter cutpoints means that no borrowers are viewed as posing acceptable risks. In Figures 3.a.1, 3.a.2, 3.b.1, 3.b.2, 3.c.1 and 3.c.2, we provide accept rates (1), the share of defaults (2) and realized default rates (3) for the prime (a), subprime (b) and government (c) segments, respectively, for the through-the- cycle (1) and stress (2) scorecards. These figures provide information for the full and target populations. All of these figures are based on the select cutpoints using the holdout sample for the given markets. The accept rate trend lines provide information similar to that found in Tables 3.a and A.4.a, but the results across segments and across scorecards for the full and target populations can be more readily compared in the figures. It is clear that the stress scorecard has reduced access to credit with lower accept rates (e.g., Figure 3.a.1.1 compared to Figure 3.a.2.1), but also results in a lower share of defaults (e.g., Figure 3.a.1.2 compared to Figure 3.a.2.2). The figures also provide the average realized default rates for those loans that were judged to be acceptable credit risk for each scorecard. In

- 219. viewing the realized default rate for the through-the-cycle scorecard, it is interesting to note that even though the scorecard and risk threshold are the same for the full and target populations (Figure 3.a.1.3), the target population performs worse in every year because it includes the riskier borrowers that are meeting the uniformly applied cutpoints. Further, even though the scorecard’s through-the- cycle values and the cutpoint are identical over time, the realized performance of the acceptable loans meeting the cutpoint is much worse in the years when the actual macroeconomic post-origination variables were at higher “stress” A Tale of Two Tensions 1019 Figure 3 � Through-the-cycle: prime accept rate. levels. This same effect can be observed for the stress scorecard (Figure 3.a.2.3), although it is attenuated because that scorecard already uses higher “stress” levels of the macroeconomic variables. Figures 3.b.2.1 (subprime) and 3.c.2.1. (government) clearly demonstrate that using a stress scorecard, with cutpoints that are reasonable for the through- the-cycle scorecard, would nearly completely eliminate any subprime or