Behavior inOrganizationsGlobal EditionThis pag.docx

- 1. Behavior in Organizations Global Edition This page intentionally left blank Jerald Greenberg E D I T I O N 10 Behavior in Organizations Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montreal Toronto Delhi Mexico City Sao Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo Global Edition Pearson Education Limited

- 2. Edinburgh Gate Harlow Essex CM20 2JE England and Associated Companies throughout the world Visit us on the World Wide Web at: www.pearsoned.co.uk © Pearson Education Limited 2011 The right of Jerald Greenberg to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Authorised adaptation from the United States edition, entitled Behavior in Organizations, 10th Edition, ISBN 978-0-13-609019-9 by Jerald Greenberg, published by Pearson Education, publishing as Prentice Hall © 2011. British Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby

- 3. Street, London EC1N 8TS. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. The use of any trademark in this text does not vest in the author or publisher any trademark ownership rights in such trademarks, nor does the use of such trademarks imply any affiliation with or endorsement of this book by such owners. ISBN: 978-1-4082-6430-0 Typeset in 10/12 Times by Integra Software Services Printed and bound by Quebecor WorldColor in The United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 14 13 12 11 10 The publisher's policy is to use paper manufactured from sustainable forests. Editorial Director: Sally Yagan Editor-in-Chief: Eric Svendsen Acquisitions Editor: Jennifer M. Collins Senior Acquisitions Editor, International: Steven Jackson Editorial Project Manager: Susan Abraham Director of Marketing: Patrice Lumumba Jones Senior Marketing Manager: Nikki Ayana Jones Marketing Manager, International: Dean Erasmus Senior Marketing Assistant: Ian Gold Senior Managing Editor: Judy Leale Production Project Manager: Kelly Warsak Senior Operations Supervisor: Arnold Vila Operations Specialist: Ilene Kahn Senior Art Director: Janet Slowik

- 4. Art Directors: Steve Frim and Janet Slowik Interior Design: Wee Design Group Cover Design: Jodi Notowitz Manager, Visual Research: Beth Brenzel Photo Researcher: Sheila Norman Manager, Rights and Permissions: Hessa Albader Permissions Coordinator: Suzanne DeWorken Manager, Cover Visual Research & Permissions: Karen Sanatar Cover Art: © Corbis Media Project Manager: Lisa Rinaldi Media Editor: Denise Vaughn Full-Service Project Management: Sharon Anderson/ BookMasters, Inc. Composition: Integra Software Services Printer/Binder: Quebecor World Color/Versailles Cover Printer: Lehigh-Phoenix Color/Hagerstown To Carolyn, For showing me what people mean when they say, “I couldn’t have done it without you.” J.G. This page intentionally left blank Brief Contents Preface 23

- 5. PART 1 Introduction to Organizational Behavior 31 Chapter 1 The Field of Organizational Behavior 31 Chapter 2 Organizational Justice, Ethics, and Corporate Social Responsibility 65 PART 2 Basic Human Processes 101 Chapter 3 Perception and Learning: Understanding and Adapting to the Work Environment 101 Chapter 4 Individual Differences: Personality, Skills, and Abilities 139 Chapter 5 Coping with Organizational Life: Emotions and Stress 173 PART 3 The Individual in the Organization 206 Chapter 6 Work-Related Attitudes: Prejudice, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment 206 Chapter 7 Motivation in Organizations 242 PART 4 Group Dynamics 279 Chapter 8 Group Dynamics and Work Teams 279 Chapter 9 Communication in Organizations 320 Chapter 10 Decision Making in Organizations 362 Chapter 11 Interpersonal Behavior at Work: Conflict, Cooperation, Trust, and Deviance 404 PART 5 Influencing Others 443 Chapter 12 Power: Its Uses and Abuses in Organizations 443 Chapter 13 Leadership in Organizations 475

- 6. PART 6 Organizational Processes 509 Chapter 14 Organizational Culture, Creativity, and Innovation 509 Chapter 15 Organizational Structure and Design 546 Chapter 16 Managing Organizational Change: Strategic Planning and Organizational Development 582 APPENDIXES Appendix 1 Learning About Behavior in Organizations: Theory and Research 618 Appendix 2 Understanding and Managing Your Career 629 Endnotes 643 Glossary 685 Company Index 704 Name Index 707 Subject Index 710 7 This page intentionally left blank Contents Preface 23 PART 1 Introduction to Organizational Behavior 31

- 7. Chapter 1 The Field of Organizational Behavior 31 � PREVIEW CASE The Talented Chief of Taleo 32 Organizational Behavior: Its Basic Nature 33 What Is the Field of Organizational Behavior All About? 33 Why Is It Important to Know About OB? 36 What Are the Field’s Fundamental Assumptions? 37 OB Recognizes the Dynamic Nature of Organizations 37 OB Assumes There Is No “One Best” Approach 38 OB Then and Now: A Capsule History 39 The Early Days: Scientific Management and the Hawthorne Studies 39 Classical Organizational Theory 40 Late Twentieth Century: Organizational Behavior as a Social Science 41 OB in Today’s Infotech Age 42 OB Responds to the Rise of Globalization and Diversity 43 International Business and the Global Economy 43 The Shifting Demographics of the Workforce: Trends Toward Diversity 46 OB Responds to Advances in Technology 49 Leaner Organizations: Downsizing and Outsourcing 50 The Virtual Organization 51 Telecommuting: Going to Work Without Leaving Home 51 OB Is Responsive to People’s Changing Expectations 53 Employees and Employers Desire Engagement 53 In Search of Flexibility: Responding to Needs of Employees 54 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 60 • Points to Ponder 61 • Experiencing OB 61 • Practicing OB 64

- 8. � CASE IN POINT Floyd’s Barbershop: A Cut Above the Rest 64 Special Sections � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS What’s in a Name? It Depends Where You Live 46 � OB IN PRACTICE Telecommuting as a Business Continuity Strategy 53 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Are I-Deals Unfair? 59 Chapter 2 Organizational Justice, Ethics, and Corporate Social Responsibility 65 � PREVIEW CASE A Huge Day’s Pay for a Seriously Bad Day’s Work 66 Organizational Justice: Fairness Matters 67 Two Important Points to Keep in Mind 67 Forms of Organizational Justice and Their Effects 68 A Neurological Basis for Responses to Injustice 71 Strategies for Promoting Organizational Justice 72 Pay Workers What They Deserve 72 Offer Workers a Voice 73 Explain Decisions Thoroughly and in a Manner Demonstrating Dignity and Respect 74 Train Workers to Be Fair 74 9

- 9. Ethical Behavior in Organizations: Its Fundamental Nature 77 What Do We Mean by Ethics? 78 Ethics and the Law 80 Why Do Some People Behave Unethically, at Least Sometimes—and What Can Be Done About It? 81 Individual Differences in Cognitive Moral Development 82 Situational Determinants of Unethical Behavior 83 Using Corporate Ethics Programs to Promote Ethical Behavior 86 Components of Corporate Ethics Programs 86 The Effectiveness of Corporate Ethics Programs 88 Ethics in the International Arena 88 Ethical Relativism and Ethical Imperialism: Two Extreme Positions 88 Three Guiding Principles of Global Ethics 89 Beyond Ethics: Corporate Social Responsibility 90 What Is Corporate Social Responsibility? 91 Forms of Socially Responsible Behavior 92 Profitability and Social Responsibility: The Virtuous Circle 93 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 95 • Points to Ponder 96 • Experiencing OB 97 • Practicing OB 99 � CASE IN POINT HP = Hidden Pretexting? What Did in Dunn? 99 Special Sections � THE ETHICS ANGLE Making A Business Case for Ethical Behavior 79 � OB IN PRACTICE Using Ethics Audits to Monitor the Triple

- 10. Bottom Line 87 � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Nike Turns the Tables on Critics of Employee Conditions 94 � VIDEO CASES Global Business at KPMG 100 Social Responsibility at Terra Cycle 100 Work/Life Balance 100 PART 2 Basic Human Processes 101 Chapter 3 Perception and Learning: Understanding and Adapting to the Work Environment 101 � PREVIEW CASE In Tune for Success 102 Social Perception and Social Identity: Understanding Others and Ourselves 103 Social Perception: What Are Others Like? 103 Social Identity: Who Am I? 103 The Attribution Process: Judging the Causes of Others’ Behavior 105 Making Correspondent Inferences: Using Acts to Judge Dispositions 106 Causal Attribution of Responsibility: Answering the Question “Why?” 107 Perceptual Biases: Systematic Errors in Perceiving Others 108 The Fundamental Attribution Error 109 The Halo Effect: Keeping Perceptions Consistent 109 The Similar-to-Me Effect: “If You’re Like Me, You Must Be Pretty Good” 110

- 11. Selective Perception: Focusing on Some Things While Ignoring Others 111 First-Impression Error: Confirming One’s Expectations 111 Self-Fulfilling Prophecies: The Pygmalion Effect and the Golem Effect 111 Stereotyping: Fitting People into Categories 114 Why Do We Rely on Stereotypes? 114 The Dangers of Using Stereotypes in Organizations 114 Perceiving Others: Organizational Applications 116 Employment Interviews: Managing Impressions to Prospective Employers 116 Performance Appraisal: Formal Judgments About Job Performance 119 10 CONTENTS Learning: Adapting to the World Around Us 120 Operant Conditioning: Learning Through Rewards and Punishments 121 Observational Learning: Learning by Imitating Others 123 Training: Learning and Developing Job Skills 124 Varieties of Training Methods 124 Principles of Learning: Keys to Effective Training 127 Organizational Practices Using Reward and Punishment 130 Organizational Behavior Management 130 Discipline: Eliminating Undesirable Organizational Behaviors 131 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 133 • Points to Ponder 135 •

- 12. Experiencing OB 135 • Practicing OB 137 � CASE IN POINT Smiling Might Not Be Such a Safe Way to Treat Safeway Customers 138 Special Sections � OB IN PRACTICE A Creative Approach to Avoiding Stereotyping 117 � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Performance Evaluations in the United States and Japan 120 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Principles for Using Discipline Fairly—and Effectively, Too 132 Chapter 4 Individual Differences: Personality, Skills, and Abilities 139 � PREVIEW CASE Kenneth Chenault: An American Success at American Express 140 Personality: Its Basic Nature 141 What Is Personality? 141 Personality and Situations: The Interactionist Approach 142 How Is Personality Measured? 144 Do Organizations Have Personalities Too? 147 Major Work-Related Aspects of Personality: The “Big Five,” Positive Versus Negative Affectivity, and Core Self-Evaluations 148 The Big Five Dimensions of Personality: Our Most Fundamental Traits 148

- 13. Positive and Negative Affectivity: Tendencies Toward Feeling Good or Bad 151 Core Self-Evaluations: How Do We Think of Ourselves? 152 Additional Work-Related Aspects of Personality 154 Machiavellianism: Using Others to Get Ahead 154 Achievement Motivation: The Quest for Excellence 155 Morning Persons and Evening Persons 158 Abilities and Skills: Having What It Takes to Succeed 160 Intelligence: Three Major Types 160 Physical Abilities: Capacity to Do the Job 164 Social Skills: Interacting Effectively with Others 165 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 167 • Points to Ponder 168 • Experiencing OB 168 • Practicing OB 171 � CASE IN POINT Howard Schultz: The Personality Behind Starbucks 171 Special Sections � OB IN PRACTICE Boosting Employees’ Self-Efficacy 153 � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Achievement Motivation and Economic Growth Around the World 159 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Are IQ Tests Inherently Unethical? 152 Chapter 5 Coping with Organizational Life: Emotions and Stress 173 � PREVIEW CASE How to Beat Call-Center Stress 174 Understanding Emotions and Mood 175 Properties of Emotions 175

- 14. Types of Emotions 175 The Basic Nature of Mood 177 CONTENTS 11 The Role of Emotions and Mood in Organizations 179 Are Happier People More Successful on Their Jobs? 179 Why Are Happier Workers More Successful? 179 Affective Events Theory 181 Managing Emotions in Organizations 183 Emotional Dissonance 183 Controlling Anger (Before It Controls You) 184 The Basic Nature of Stress 185 Stressors in Organizations 186 The Cognitive Appraisal Process 187 Bodily Responses to Stressors 188 Major Causes of Stress in the Workplace 190 Occupational Demands 190 Conflict Between Work and Nonwork 190 Sexual Harassment: A Pervasive Problem in Work Settings 191 Role Ambiguity: Stress from Uncertainty 192 Overload and Underload 193 Responsibility for Others: A Heavy Burden 193 Lack of Social Support: The Costs of Isolation 193 Adverse Effects of Organizational Stress 194 Lowered Task Performance—But Only Sometimes 194 Desk Rage 195 Stress and Health: The Silent Killer 195

- 15. Reducing Stress: What Can Be Done? 197 Employee Assistance Programs and Stress Management Programs 197 Wellness Programs 197 Managing Your Own Stress 198 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 200 • Points to Ponder 201 • Experiencing OB 202 • Practicing OB 203 � CASE IN POINT A Basketball Court Judge Faces a Federal Court Judge 203 Special Sections � OB IN PRACTICE Managing Anger in the Workplace 185 � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Do Women and Men Respond Differently to Stress? 196 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Companies and Employee Health: An Invitation for Big Brother? 199 � VIDEO CASES Training and Development 204 Managing Stress 204 PART 3 The Individual in the Organization 206 Chapter 6 Work-Related Attitudes: Prejudice, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment 206 � PREVIEW CASE A Second Chance 207 Attitudes: What are They? 207 Basic Definitions 208

- 16. Three Essential Components of Attitudes 208 Prejudice and Discrimination: Negative Attitudes and Behavior Toward Others 209 The Challenges of Organizational Demography 209 Anatomy of Prejudice: Some Basic Distinctions 210 Everyone Can Be a Victim of Prejudice and Discrimination! 211 12 CONTENTS Strategies for Overcoming Workplace Prejudice: Managing a Diverse Workforce 215 Affirmative Action 215 Diversity Management: Orientation and Rationale 216 Diversity Management: What are Companies Doing? 217 Job Satisfaction: Its Nature and Major Theories 220 The Nature of Job Satisfaction: Fundamental Issues 220 The Dispositional Model of Job Satisfaction 222 Value Theory of Job Satisfaction 223 Social Information Processing Model 223 Consequences of Job Dissatisfaction—and Ways to Reduce Them 224 Employee Withdrawal: Voluntary Turnover and Absenteeism 224 Job Performance: Are Dissatisfied Employees Poor Performers? 228 Job Satisfaction and Injuries: Are Happy Workers Safe Workers? 229 Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction 230

- 17. Organizational Commitment: Attitudes Toward Companies 231 Varieties of Organizational Commitment 232 Why Strive for an Affectively Committed Workforce? 233 How to Promote Affective Commitment 236 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 237 • Points to Ponder 238 • Experiencing OB 238 • Practicing OB 240 � CASE IN POINT Domino’s Pizza Takes a Bite Out of Turnover 240 Special Sections � OB IN PRACTICE How the “Good Hands People” Use Diversity as a Competitive Weapon 220 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Promoting Job Satisfaction by Treating People Ethically 231 � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Does Absenteeism Mean the Same Thing in Canada and China? 235 Chapter 7 Motivation in Organizations 242 � PREVIEW CASE PAC Engineering: Employee Motivation, Different Priorities for Different Territories 243 Motivation in Organizations: Its Basic Nature 244 Components of Motivation 244 Three Key Points About Motivation 245

- 18. Motivating by Enhancing Fit with an Organization 246 Motivational Traits and Skills 247 Organizational Factors: Enhancing Motivational Fit 247 Motivating by Setting Goals 248 Goal-Setting Theory 248 Guidelines for Setting Effective Performance Goals 250 Motivating by Being Equitable 254 Equity Theory: Balancing Outcomes and Inputs 254 Managerial Implications of Equity Theory 258 Motivating by Altering Expectations 260 Basic Elements of Expectancy Theory 260 Putting Expectancy Theory to Work: Key Managerial Implications 263 Motivating by Structuring Jobs to Make Them Interesting 266 Job Enlargement and Job Enrichment 266 The Job Characteristics Model 268 Designing Jobs That Motivate: Managerial Guidelines 270 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 273 • Points to Ponder 274 • Experiencing OB 274 • Practicing OB 276 � CASE IN POINT Google: Searching for a Better Way to Work 276 CONTENTS 13 Special Sections � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Inequity in Housework:

- 19. Comparing Married Women and Men 258 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Should Doctors Be Paid for Their Performance? 265 � OB IN PRACTICE Autonomy Is Not Music to the Maestro’s Ears 269 � VIDEO CASES Diversity at KPMG 277 Motivating Employees at KPMG 278 PART 4 Group Dynamics 279 Chapter 8 Group Dynamics and Work Teams 279 � PREVIEW CASE Making a “Better Place” One Electric Vehicle at a Time 280 Groups at Work: Their Basic Nature 281 What Is a Group? 281 What Types of Groups Exist? 283 Why Do People Join Groups? 284 The Formation of Groups 285 The Five-Stage Model of Group Formation 285 The Punctuated-Equilibrium Model 286 The Structural Dynamics of Work Groups 287 Roles: The Hats We Wear 287 Norms: A Group’s Unspoken Rules 289 Status: The Prestige of Group Membership 290 Cohesiveness: Getting the Team Spirit 291 Individual Performance in Groups 292

- 20. Social Facilitation: Working in the Presence of Others 292 Social Loafing: “Free Riding” When Working with Others 294 Teams: Special Kinds of Groups 297 Defining Teams and Distinguishing Them from Groups 297 Types of Teams 299 Creating and Developing Teams: A Four-Stage Process 303 Effective Team Performance 304 How Successful Are Teams? 305 Potential Obstacles to Success: Why Some Teams Fail 305 Developing Successful Teams 306 Compensate Team Performance 306 Recognize the Role of Team Leaders 308 Communicate the Urgency of the Team’s Mission 309 Train Members in Team Skills 309 Promote Cooperation Within and Between Teams 312 Select Team Members Based on Their Skills or Potential Skills 313 A Cautionary Note: Developing Successful Teams Requires Patience 314 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 315 • Points to Ponder 316 • Experiencing OB 316 • Practicing OB 318 � CASE IN POINT Inside the Peloton: Social Dynamics of the Tour de France 318 Special Sections � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Is Social Loafing a Universal Phenomenon? 296 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Fairness in Teams: What Are Members

- 21. Looking For? 308 � OB IN PRACTICE Making Cross-National Team Successful 313 14 CONTENTS Chapter 9 Communication in Organizations 320 � PREVIEW CASE Reducing Interruptions High-Tech Style at Microsoft and IBM 321 Communication: Its Basic Nature 323 Defining Communication and Describing the Process 323 Purposes and Levels of Organizational Communication 324 Verbal and Nonverbal Communication: Messages With and Without Words 326 Verbal Media 327 Matching the Medium to the Message 328 Nonverbal Communication 330 The Role of Technology: Computer-Mediated Communication 332 Synchronous Communication: Video-Mediated Communication 333 Asynchronous Communication: E-Mail and Instant Messaging 334 Does High-Tech Communication Dehumanize the Workplace? 335 Formal Communication in Organizations 337 Organizational Structure Influences Communication 337 Downward Communication: From Supervisor to Subordinate

- 22. 338 Upward Communication: From Subordinate to Superior 339 Lateral Communication: Coordinating Messages Among Peers 340 Communicating Inside Versus Outside the Organization: Strategic Communication 341 Informal Communication Networks: Behind the Organizational Chart 342 Organizations’ Hidden Pathways 342 The Nature of the Grapevine 343 Rumors and How to Combat Them 344 Individual Differences in Communication 346 Sex Differences in Communication: Do Women and Men Communicate Differently? 346 Cross-Cultural Differences in Communication 347 Improving Your Communication Skills 349 Use Jargon Sparingly 349 Be Consistent in What You Say and Do 350 Become an Active, Attentive Listener 351 Gauge the Flow of Information: Avoiding Overload 353 Give and Receive Feedback: Opening Channels of Communication 354 Be a Supportive Communicator: Enhancing Relationships 355 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 356 • Points to Ponder 358 • Experiencing OB 358 • Practicing OB 360 � CASE IN POINT ARM's Virtual Success Story 361 Special Sections � OB IN PRACTICE The Downside of Communicating Layoffs Via E-Mail 331

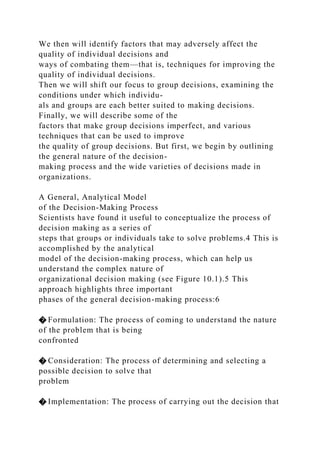

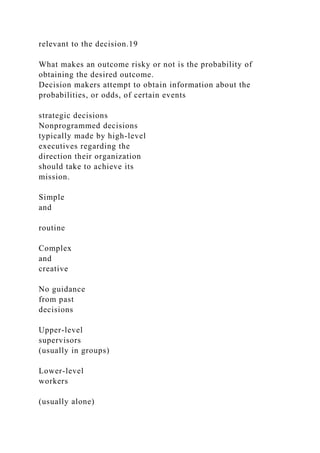

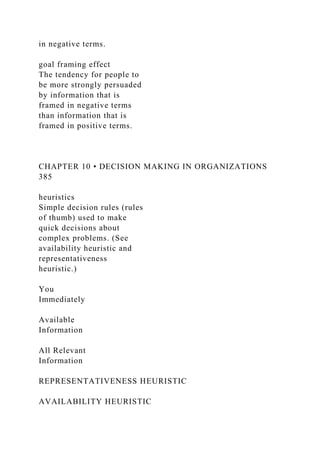

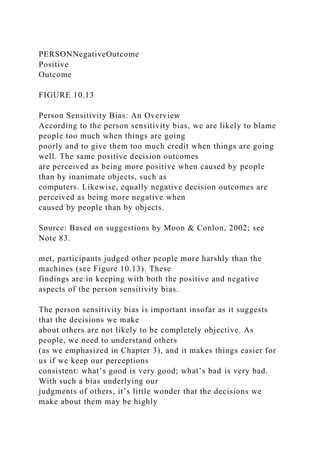

- 23. � THE ETHICS ANGLE Should Employers Be Monitoring Employees’ Computer Activities? 336 � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Promoting Cross-Cultural Communication 348 Chapter 10 Decision Making in Organizations 362 � PREVIEW CASE How Should We Handle the Tiger Affair? 363 A General, Analytical Model of the Decision-Making Process 364 Decision Formulation 364 Decision Consideration 366 Decision Implementation 366 The Broad Spectrum of Organizational Decisions 367 Programmed Versus Nonprogrammed Decisions 367 Certain Versus Uncertain Decisions 368 Top-Down Versus Empowered Decisions 371 CONTENTS 15 Factors Affecting Decisions in Organizations 372 Individual Differences in Decision Making 372 Group Influences: A Matter of Trade-Offs 375 Organizational Influences on Decision Making 377 How Are Individual Decisions Made? 379 The Rational-Economic Model: In Search of the Ideal Decision 379

- 24. The Administrative Model: Acknowledging the Limits of Human Rationality 379 Image Theory: An Intuitive Approach to Decision Making 380 The Imperfect Nature of Individual Decisions 382 Framing Effects 383 Reliance on Heuristics 385 The Inherently Biased Nature of Individual Decisions 386 Group Decisions: Do Too Many Cooks Spoil the Broth? 391 When Are Groups Superior to Individuals? 391 When Are Individuals Superior to Groups? 392 Techniques For Improving the Effectiveness of Decisions 393 Training Individuals to Improve Group Performance 393 Techniques for Enhancing Group Decisions 394 Group Decision Support Systems 397 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 398 • Points to Ponder 400 • Experiencing OB 400 • Practicing OB 402 � CASE IN POINT Coca-Cola: Deciding on the Look 402 Special Sections � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS How Does National Culture Affect the Decision-Making Process? 367 � OB IN PRACTICE Strategies for Avoiding Groupthink 377 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Why Do People Make Unethical Decisions? Bad Apples, Bad Cases, and Bad Barrels 381 Chapter 11 Interpersonal Behavior at Work: Conflict,

- 25. Cooperation, Trust, and Deviance 404 � PREVIEW CASE NASCAR: The Etiquette of Drafting 405 Psychological Contracts and Trust: Building Blocks of Working Relationships 406 Psychological Contracts: Our Expectations of Others 406 Trust in Working Relationships 409 Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Going Above and Beyond Formal Job Requirements 413 Forms of OCB 413 Why Does OCB Occur? 414 Does OCB Really Matter? 414 Cooperation: Providing Mutual Assistance 416 Cooperation Between Individuals 416 Cooperation Between Organizations: Interorganizational Alliances 419 Conflict: The Inevitable Result of Incompatible Interests 421 Types of Conflict 421 Causes of Conflict 421 Consequences of Conflict 423 Managing Conflict Through Negotiation 423 Alternative Dispute Resolution 425 Deviant Organizational Behavior 426 Constructive and Destructive Workplace Deviance 427 Whistle-Blowing: Constructive Workplace Deviance 428 Cyberloafing: Deviant Behavior Goes High-Tech 430 Workplace Aggression and Violence 431

- 26. 16 CONTENTS Abusive Supervision: Workplace Bullying 434 Employee Theft 435 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 437 • Points to Ponder 438 • Experiencing OB 438 • Practicing OB 440 � CASE IN POINT Southwest Airlines: Profits from People 440 Special Sections � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Psychological Contracts in China and the United States: Are They the Same 409 � OB IN PRACTICE How to Promote OCB 416 � THE ETHICS ANGLE The Benefits of Promoting Conflict 424 � VIDEO CASES Effective Versus Ineffective Communication 441 Groups and Teams at Kluster 441 Technology and the Tools of Communication 441 PART 5 Influencing Others 443 Chapter 12 Power: Its Uses and Abuses in Organizations 443 � PREVIEW CASE Abuse of Power or “An Indiscriminate Jerk”? 444 Influence: A Basic Organizational Process 445 Tactics for Exerting Influence 445 Can Managers Learn to Use Influence More Effectively? 446

- 27. Individual Power: Sources and Uses 448 Position Power: Influence That Comes with the Office 448 Personal Power: Influence That Comes from the Individual 449 How Is Individual Power Used? 450 When Can Being Powerful Be a Liability? 452 Empowerment: Sharing Power with Employees 453 Do Employees Like Being Empowered? 454 Empowerment Climate 455 The Power of Organizational Groups 457 The Resource-Dependency Model: Controlling Critical Resources 457 The Strategic Contingencies Model: Power Through Dependence 459 Sexual Harassment: A Serious Abuse of Power 461 Nature and Scope of Sexual Harassment 461 Managing Sexual Harassment in the Workplace: What to Do 462 Organizational Politics: Selfish Uses of Power 465 Forms of Political Behavior 466 Why Does Political Behavior Occur? 467 The Impact of Organizational Politics 469 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 470 • Points to Ponder 471 • Experiencing OB 471 • Practicing OB 473 � CASE IN POINT The Smith Brothers’ Low-Key Approach to Organizational Power 473 Special Sections � OB IN PRACTICE Cultivating Your Own Influence Skills 447

- 28. � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Comparing Reactions to Empowerment in Four Different Nations 456 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Dispelling Myths about Sexual Harassment 464 Chapter 13 Leadership in Organizations 475 � PREVIEW CASE The Woman Who Saved the Chicken Fajitas 476 The Nature of Leadership 477 Defining Leadership 477 Important Characteristics of Leadership 477 Leaders Versus Managers: A Key Distinction—At Least in Theory 478 CONTENTS 17 The Trait Approach to Leadership: Having the Right Stuff 480 The Great Person Theory 480 Transformational Leaders: Special People Who Make Things Happen 481 Leadership Behavior: What Do Leaders Do? 485 Participative Versus Autocratic Leadership Behaviors 485 Person-Oriented Versus Production-Oriented Leaders 487 Developing Successful Leader Behavior: Grid Training 488 Leaders and Followers 489 The Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Model: The Importance of Being in the “In-Group” 489 The Challenge of Leading Work Teams 491

- 29. Contingency Theories of Leader Effectiveness 492 LPC Contingency Theory: Matching Leaders and Tasks 493 Situational Leadership Theory: Adjusting Leadership Style to the Situation 495 Path-Goal Theory: Leaders as Guides to Valued Goals 496 Leadership Development: Bringing Out the Leader Within You 498 360-Degree Feedback 499 Networking 499 Executive Coaching 501 Mentoring 501 Job Assignments 502 Action Learning 502 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 504 • Points to Ponder 505 • Experiencing OB 505 • Practicing OB 507 � CASE IN POINT A New Era for Newark 507 Special Sections � OB IN PRACTICE Coaching Tips from Some of the Best 497 � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Guanxi: Social Networking in China 500 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Using Leadership Development Techniques to Promote Authentic Leaders 503 � VIDEO CASES Leadership at Kluster 508 Decision Making at Insomnia Cookies 508

- 30. PART 6 Organizational Processes 509 Chapter 14 Organizational Culture, Creativity, and Innovation 509 � PREVIEW CASE The Global Face of Social Networking 510 Organizational Culture: Its Basic Nature 511 Organizational Culture: A Definition 511 Core Cultural Characteristics 511 Strength of Organizational Culture: Strong and Weak 514 Cultures Within Organizations: One or Many? 514 The Role of Culture in Organizations 514 Forms of Organizational Culture: The Competing Values Framework 515 Creating, Transmitting and Changing Organizational Culture 518 How Is Organizational Culture Created? 518 Tools for Transmitting Culture 519 Why and How Does Organizational Culture Change? 522 Creativity in Individuals and Teams 526 Components of Individual and Team Creativity 526 A Model of the Creative Process 528 18 CONTENTS Promoting Creativity in Organizations 529 Training People to be Creative 529 Developing Creative Work Environments 532 The Process of Innovation 534 Major Forms of Innovation 534

- 31. Targets of Innovation 536 Conditions Required for Innovation to Occur 537 Stages of the Organizational Innovation Process 537 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 540 • Points to Ponder 542 • Experiencing OB 542 • Practicing OB 544 � CASE IN POINT Amazon.com: Innovation via the “Two-Pizza Team” 544 Special Sections � THE ETHICS ANGLE Building an Ethical Organizational Culture 526 � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Where in the World is Entrepreneurial Creativity Promoted? 534 � OB IN PRACTICE How to Inspire Innovation 540 Chapter 15 Organizational Structure and Design 546 � PREVIEW CASE Verizon and McAfee Head for “the Cloud” Together 547 Organizational Structure: The Basic Dimensions of Organizations 548 Hierarchy of Authority: Up and Down the Organizational Ladder 548 Span of Control: Breadth of Responsibility 550 Division of Labor: Carving Up the Work to Be Done 551 Line Versus Staff Positions: Decision Makers Versus Advisers 552 Decentralization: Delegating Power Downward 552

- 32. Departmentalization: Ways of Structuring Organizations 554 Functional Organizations: Departmentalization by Task 554 Product Organizations: Departmentalization by Type of Output 556 Matrix Organizations: Departmentalization by Both Function and Product 557 Organizational Design: Coordinating the Structural Elements of Organizations 559 Classical and Neoclassical Approaches: The Quest for the One Best Design 560 The Contingency Approach: Design According to Environmental Conditions 561 Mintzberg’s Framework: Five Organizational Forms 563 The Vertically Integrated Organization 566 Team-Based Organizations 567 A Strategic Approach to Designing Organizations 568 Strategy 569 Contingency Factors 569 Task Qualities and Coordination Mechanisms 570 Structural or Design Feature 571 Interorganizational Designs: Joining Multiple Organizations 573 Boundaryless Organizations: Eliminating Walls 573 Conglomerates: Diversified “Megacorporations” 574 Strategic Alliances: Joining Forces for Mutual Benefit 574 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 577 • Points to Ponder 579 • Experiencing OB 579 • Practicing OB 581

- 33. � CASE IN POINT Commercial Metals Company “Steels” the Show 581 CONTENTS 19 Special Sections � THE ETHICS ANGLE How Fair is Centralization? It Depends Who You Ask 555 � OB IN PRACTICE Organizational Design Strategies for the Information Age 572 � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS The Changing Economic and Regulatory Factors Influencing Organizational Design 577 Chapter 16 Managing Organizational Change: Strategic Planning and Organizational Development 582 � PREVIEW CASE Ghosn Overcomes Cultural Barriers at Nissan 583 The Prevalence of Change in Organizations 584 The Message Is Clear: Change or Disappear! 584 Change Is a Global Phenomenon 585 The Nature of the Change Process 586 Targets: What, Exactly, Is Changed? 586 Magnitude: How Much Is Changed? 588 Forces: Why Does Unplanned Change Occur? 588 Strategic Planning: Deliberate Change 592

- 34. Basic Assumptions About Strategic Planning 592 About What Do Companies Make Strategic Plans? 593 The Strategic Planning Process: Making Change Happen 595 Resistance to Change: Maintaining the Status Quo 598 Individual Barriers to Change 598 Organizational Barriers to Change 599 Readiness for Change: When Will Organizational Change Occur? 600 Factors Affecting Resistance to Change 601 How Can Resistance to Organizational Change Be Overcome? 602 Organizational Development Interventions: Implementing Planned Change 605 Management by Objectives: Clarifying Organizational Goals 605 Survey Feedback: Inducing Change by Sharing Information 607 Appreciative Inquiry 608 Action Labs 609 Quality of Work Life Programs: Humanizing the Workplace 609 Critical Questions About Organizational Development 610 Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 613 • Points to Ponder 614 • Experiencing OB 614 • Practicing OB 615 � CASE IN POINT The Swiss Post: The “Yellow Giant” Moves 615 Special Sections � TODAY’S DIVERSE AND GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Strategic Values: More American Than Universal 598 � OB IN PRACTICE Making Changes Stick: Tips from Three

- 35. Established Organizations 606 � THE ETHICS ANGLE Is Organizational Development Inherently Unethical? 611 � VIDEO CASES Change, Creativity, and Innovation at Terra Cycle 616 Organizational Culture at Terra Cycle 617 Inside Student Advantage 617 Appendixes Appendix 1 Learning About Behavior in Organizations: Theory and Research 618 Isn't It All Just Common Sense? 618 Theory: an Indispensable Guide to Organizational Research 619 Survey Research: The Correlational Method 621 Experimental Research: The Logic of Cause and Effect 624 20 CONTENTS Appendix 2 Understanding and Managing Your Career 629 The Nature of Careers 629 Getting Started: Making Career Choices 632 Managing Established Careers 637 Endnotes 643 Glossary 685 Company Index 704 Name Index 707 Subject Index 710 CONTENTS 21

- 36. This page intentionally left blank Preface Welcome to Behavior in Organizations, 10th Edition. As with the tenth iteration of anything, it’s a milestone. And, by nature, milestones encourage us to look at where we’ve been. In this case, I see a book that is entering its fourth decade of publication. This edition hardly could be more different from the first edition—published in the early 1980s—in scope, style, and coverage. But, as the epigram goes, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose (“the more things change, the more they remain the same”). For Behavior in Organizations, what remained the same is fundamental—the book’s commit- ment to reflecting the nature of organizational behavior (OB). No matter where the field has been, Behavior in Organizations was there to capture its essence. This commitment remains as strong as ever in the current edition, but accomplishing this objective also has been more challenging. For this I can thank the unprecedented speed with which contemporary organizations have been changing, making them moving targets for scientists intent on studying the behavior of people within them. And as they work to get a grip on the (sometime seismically) shifting terrain of the nature of organizations, so too have I endeavored to characterize what OB scientists and

- 37. practitioners do. This challenge is one I approach with alacrity because the field’s changes have kept it exciting and vibrant. In particular, they have reflected a new focus on issues that are not only scientifically important but that also have considerable practical value. It’s science that’s relevant to real-world issues, and this makes it incredibly valuable. OB has positioned itself as the field that provides insight into the dynamic relationships between individuals, groups/teams, and entire organizations and, of course, their interrelationships with the economic, cultural, and social environment. We trade in research and theory, but these tools do not suffer from ivory tower elitism. Instead, the field of OB is focused on applying its highly developed analytical tools to understanding something very real and dynamic—the behavior of people in the workplace. Over the years, I’ve seen shifts in directions, but OB is now facing the issue of relevance instead of skirting it. Accordingly, this book now provides more insight into what actually is occurring in the workplace. In other words, as the field keeps apace with the workplace, I keep my fingers on its pulse. And those fingers are connected directly to the keyboard from which this book has emerged. I became well aware of these changes as I researched this edition. Some of our concepts (e.g., jus- tice, trust, diversity) have received more attention than in years past, earning them increased emphasis in this edition. On the other hand, some once-dominant conceptualizations (e.g., Maslow’s need hierar- chy theory, Herzberg’s two-factor theory) have faded from our radar screens, leading me to remove

- 38. them from the book. These topics are interesting and have had impact, but they are more yesterday than today. As such, they have limited value in a book I claim to be a snapshot of OB as we currently find it. Perhaps what surprised me most was the huge number of changes in the businesses highlighted as examples in the previous edition. Many of these organizations no longer exist. Even more have been transformed in ways that now make them inappropriate as examples of the practice or phe- nomena I once associated with them. Inevitably, some of the companies described in this book will have altered their ways of operation still further by the time you read this, making some of my examples imperfect. Unfortunate as this is, it simply is a by product of studying a dynamic field. Major Objective: To Spotlight Organizational Behavior People enjoy learning about behavior in organizations. It gives us unique insight into everyday processes and phenomena we often take for granted, knowledge that helps us understand a key part of the world in which we live. For a book such as this, the implication is that the material must be accessible and relevant to readers. I have been very deliberate in my effort to incorporate these qualities into this book. Accessibility to Readers In preparing this edition, I have adopted a very simple assumption: Unless readers find the mate- rial accessible and engaging, they will fail to get anything out of it—if they even bother to read it at all. With this in mind, I have done several things that may be

- 39. seen throughout this book. 23 � As always, I have gone out of my way to use a friendly and approachable writing style, speak- ing directly to readers in straightforward prose. At the same time, I have done my best to refrain from condescension (by speaking down to readers) and elitism (by going over their heads). � By carefully selecting material to which students can relate— such as accounts of organiza- tional practices in companies with which they may be familiar— they are likely to find the material engaging. In this edition, for example, organizations such as Facebook and Apple, and cross-functional teams such as the Dave Matthews Band, are mentioned. � Key points are easy to find because of the way the book is designed and by features such as key terms appearing in margins and a “Summary and Review of Learning Objectives” appearing at the end of each chapter. � Graphics are used to enhance explanations of material for visually oriented learners. For exam- ple, the “talking graphics” I’ve used for many editions help readers take away the key find- ings of research appearing in graphs. Using arrows to point directly to the important aspects of research findings is the next best thing to having an instructor present to point them out.

- 40. These are among the several key features that help bring the material to life for students by making a fascinating topic readily understandable. Focusing on Relevance The field of OB is not about curiosity for its own sake. Rather, it’s about finding real, scientifically based answers to practical questions. Thus, relevance is vital. Theories and research are impor- tant, many students believe, so long as they offer insight into appropriate action—that is, what to do and why. In preparing this book, my mission was to spotlight this relevance in a form that would enlighten the target audience—college students at all levels who desire to learn about the complexities of human behavior in organizations. I do this in three ways. First, in each chapter I provide concrete information on putting organizational behavior to prac- tical use in special sections titled “OB in Practice.” This feature describes current practices being used in companies or principles that readily lend themselves to application. Examples include: � How the “Good Hands People” Use Diversity as a Competitive Weapon (Chapter 6) � Organizational Design Strategies for the Information Age (Chapter 15) � Making Changes Stick: Tips from Three Established Organizations (Chapter 16) A second way in which I attempt to make the material relevant is by highlighting two significant realities of contemporary organizations—shifts in demographic

- 41. diversity and rapid globalization of the business environment. I do this in sections titled, “Today’s Diverse and Global Organizations.” These sections highlight ways in which differences between individuals with respect to their race, gender, sex- ual preference, or nationality impact various OB phenomena. Some examples include the following: � Nike Turns the Tables on Critics of Employee Conditions (Chapter 2) � Do Men and Women Respond Differently to Stress? (Chapter 5) � Inequity in Housework: Comparing Married Women and Men (Chapter 7) � How Does National Culture Affect the Decision-Making Process? (Chapter 10) � The Changing Economic and Regulatory Factors Influencing Organizational Design (Chapter 15) The third way in which I focus on relevance is by highlighting a topic that has been occupy- ing the popular press in recent years—ethics (or lack thereof). As ethics scandals proliferate, it is especially important to examine insight offered by the field of OB. I do this in the present book in a special feature called “The Ethics Angle.” Several such sections are as follows: � Making a Business Case for Ethical Behavior (Chapter 2) � Should Doctors Be Paid for Their Performance? (Chapter 7) � Why Do People Make Unethical Decisions? Bad Apples, Bad Cases, and Bad Barrels (Chapter 10) A Careful Balancing Act

- 42. Throughout this book I found it necessary to balance coverage in two ways: (a) in striking a balance between discussions of basic science and practical application and (b) in presenting material designed to impart knowledge intended to develop skills. 24 PREFACE Balancing Basic Science and Practical Application Because the field of OB is a blend of research, theory, and practical application, so too, quite deliberately, is this book. Indeed, I have taken extensive steps to ensure that it is the best of these seemingly disparate worlds. Consider just a few examples: � In Chapter 3, I cover theories of learning and how these are involved in such organizational practices as training, organizational behavior management, and discipline. � In Chapter 6, specific ways in which the various theories of motivation can be put into practice are discussed. � In Chapter 10, it is not only various scientific studies of decision making that are identified, but also various practices that can be, and are being, followed to enhance the effectiveness of group decisions. Beyond simply indicating how various research findings and theories may be applied, I also focus on application by adopting a hands-on approach. This is

- 43. done by offering concrete, “how to” suggestions for readers. These are not only useful by themselves, but because they are derived from OB research and theory, they also provide clear illustrations of the field’s practical utility. By weaving such recommendations throughout this book, OB is brought to life for readers at every juncture. Just a few examples include how to: � Properly use communication media (Chapter 9) � Brainstorm effectively (Chapter 10) � Promote trust in organizations (Chapter 11) By focusing on how findings from OB research may be applied in organizations, I am taking what amounts to an evidence-based approach. In recent years, so-called “evidence-based” movements have emerged in such applied fields as medicine, nursing, education, and manage- ment. The idea underlying these approaches is that guidelines for practice should be based on research findings. Although this idea may be novel to some fields, using research to inform practice is inherent in the nature of OB. For this reason, the practice of applying research and theory to organizational issues (evidence-based practice) and relying on knowledge of practical problems as input into research and theory (practice-based evidence) is a hallmark of the field of OB—and for this reason, it is emphasized in this book. Balancing Knowledge and Skills Educators tell us that there is a fundamental distinction between teaching people about something—providing knowledge—and showing them how to do it—developing their skills. In

- 44. the field of OB, this distinction becomes blurred. After all, to appreciate fully how to do something, you have to have the requisite knowledge. For this reason, I pay attention to both knowledge and skills in this book. Consider the following illustrations: � Chapter 5 investigates ways in which stress operates in the workplace. Beyond this, I also present an exercise to help readers recognize how they can build resilience as a way of alleviating the adverse effects of stress. � Chapter 9 discusses the nature of the communication process. In addition, to help readers be- come effective communicators I include an exercise designed to promote active listening skills. � Chapter 13 describes the nature of leadership. With an eye toward helping readers develop their own skills, I present a section that allows people to assess their own styles as leaders. � Chapter 16 explains not only the reasons underlying individuals’ resistance to organizational change but also various ways in which this may be overcome. In addition, I give students an opportunity to practice overcoming resistance to change in an exercise. By doing these things—not only in these examples, but throughout the book—I intend not only to help readers understand OB, but also to enable them to practice it in their own lives. New Coverage

- 45. In revising this book, I made many changes. Some came in the process of seeking that balance to which I just referred, and others were necessitated by my ongoing commitment to highlighting PREFACE 25 the latest advances in the field and to updating examples. Many of the changes are subtle, refer- ring only to how a topic is framed relative to others. A good many others are more noticeable and involve the shifting of major sections into new places and the addition of brand new ones. Here are just a few of the new topics and the chapters in which they appear: � Compressed workweeks (Chapter 1) � Idiosyncratic work arrangements (i-deals) (Chapter 1) � Multifoci approach to organizational justice (Chapter 2) � Neurological bases of organizational justice (Chapter 2) � Basking in reflected glory/cutting off reflected failure (Chapter 3) � Active learning techniques (Chapter 3) � Cascading model of emotional intelligence (Chapter 4) � National differences in expressivity (Chapter 5) � Effects of mood on memory (Chapter 5) � Preferential and nonpreferential affirmative action (Chapter 6) � Affinity groups (part of expanded coverage of diversity) (Chapter 6) � Strongest motivators for people at different organizational levels (Chapter 7) � Pay-for-performance among physicians (Chapter 7)

- 46. � Cross-training (Chapter 8) � Shared mental models (Chapter 8) � Role of media richness in recruitment ads (Chapter 9) � Communicating layoffs via e-mail (Chapter 9) � Why people make unethical decisions (Chapter 10) � Indecisiveness (Chapter 10) � Swift trust (Chapter 11) � Developing trustworthiness (Chapter 11) � Straightforwardness (Chapter 12) � Political skill (Chapter 12) � Assessment centers (Chapter 13) � Promoting authentic leadership (Chapter 13) � Ethical and customer-centered organizational culture (Chapter 14) � Openness to experience and support for creativity (Chapter 14) � Strategic approach to organizational design (Chapter 15) � Communities of practice (Chapter 15) � Product offshoring, services offshoring, and innovation offshoring (Chapter 16) Pedagogical Features Faculty members who have adopted the previous edition of this book have valued its many pedagogical features. They will be pleased to find that these have returned, although updated and revised, of course. End-of-Chapter Pedagogical Features Two groups of pedagogical features may be found at the end of each chapter. The first, named “Points to Ponder,” includes three types of questions: � Questions for Review. These are designed to help students determine the extent to which they picked up the major points contained in each chapter.

- 47. � Experiential Questions. These questions get students to understand various OB phenomena by thinking about experiences in their work lives. � Questions to Analyze. The questions in this category are designed to help readers think about the connections between various OB phenomena and/or how they may be applied in organizational situations. The second category of end-of-chapter pedagogical features is referred to as “Experiencing OB.” This includes the following three types of experiential exercises. � Individual Exercise. Students can complete these exercises on their own to gain personal insight into various OB phenomena. 26 PREFACE � Group Exercise. By working in small groups, students will be able to experience an important OB phenomenon or concept. The experience itself also will help them develop team-building skills. � Practicing OB. This exercise is applications-based. It describes a hypothetical problem situa- tion and challenges the reader to explain how various OB practices can be applied to solving it. Case Features

- 48. Each chapter contains two cases. Positioned at the beginning of the chapter, a Preview Case is designed to set up the material that follows by putting it in the context of a real organizational event. These are either completely new to this edition or updated considerably. A few examples of new Preview Cases include the following: � The Talented Chief of Taleo (Chapter 1) � A Huge Day’s Pay for a Seriously Bad Day’s Work (Chapter 2) � In Tune for Success (Chapter 3) � How to Beat Call-Center Stress (Chapter 5) � A Second Chance (Chapter 6) � PAC Engineering: Employee Motivation, Different Priorities for Different Territories (Chapter 7) � The Woman Who Saved the Chicken Fajitas (Chapter 13) � The Global Face of Social Networking (Chapter 14) � Ghosn Overcomes Cultural Barriers at Nissan (Chapter 16) The end-of-chapter case, Case in Point, is designed to review the material already covered and to bring it to life. Specific tie-ins are made by use of discussion questions appearing after each Case in Point feature. These also are new or updated for this edition. Several examples of new cases include the following: � Floyd’s Barbershop: A Cut Above the Rest (Chapter 1) � HP = Hidden Pretexting? What Did In Dunn? (Chapter 2) � Domino’s Pizza Takes a Bite Out of Turnover (Chapter 6) � Inside the Peloton: Social Dynamics of the Tour de France (Chapter 8) � ARM’s Virtual Success Story (Chapter 9) � A New Era for Newark (Chapter 13) � The Swiss Post: The “Yellow Giant” Moves (Chapter 16)

- 49. Updated Supplements Packages Updating the book has required revising the supplements packages. This was done both for supple- ments available to faculty members who adopt this book in their classes and for their students. Supplements for Instructors At www.pearsonglobaleditions.com/greenberg, instructors can access a variety of print, digital, and presentation resources available with this text in downloadable format. Registration is sim- ple and gives you immediate access to new titles and new editions. As a registered faculty mem- ber, you can download resource files and receive immediate access and instructions for installing course management content on your campus server. If you need assistance, our dedicated technical support team is ready to help with the media supplements that accompany this text. Visit 247pearsoned.custhelp.com for answers to frequently asked questions and toll-free user support phone numbers. The following supplements are available to adopting instructors (for detailed descriptions, please visit www.pearsonglobaleditions.com/greenberg): � Instructor’s Manual. Materials designed to provide ideas and resources for classroom teaching have been updated and revised. � Test Item File. Questions that require students to apply the information about which they’ve read in the text have been revised and updated to

- 50. support changes in this edition. Questions are also tagged to reflect the AACSB Learning Standards. PREFACE 27 � TestGen Test Generating Software. Test management software containing all the material from the Test Item File is available. This software is completely user friendly and allows instructors to view, edit, and add test questions with just a few mouse clicks. � PowerPoint Presentation. A ready-to-use PowerPoint slideshow has been designed for classroom presentation. Use it as is, or edit content to fit your individual classroom needs. Supplements for Students Several supplemental materials are available to help students at this book’s companion Web site, www.pearsonglobaleditions.com/greenberg. These include the following: � Learning Objectives. This is a list of the six major learning objectives for each chapter. � Chapter Quizzes. These are 20-item quizzes that students can use to assess their own famil- iarity with the content of each chapter. As a helpful feature, online “hints” are provided. � Internet Exercises. Each chapter contains three exercises that require students to tap resources

- 51. found on the Internet to expand their understanding of the material in each chapter. � Student PowerPoints. A set of PowerPoint slides is given for each chapter. These outline the major points covered. Finally—and Most Importantly—Acknowledgments Writing is a solitary task. In contrast, the process of turning the millions of bytes of information I generate as a content provider into this beautiful book is anything but solitary. To the contrary, it requires the highly coordinated efforts of a team of dedicated professionals in different profes- sions, all of whom lend their considerable talents toward making this book a reality. In preparing this text, I have been fortunate to work with a variety of hardworking people whose efforts are reflected on every page. Although I cannot possibly thank all of them here, I wish to express my appreciation to those whose help has been most valuable. To begin, I must thank to my former coauthor on this book, Robert A. Baron. His guidance has helped me develop as a textbook author and his friendship over many decades has given me the confidence to undertake the challenges of authoring. Second, I acknowledge sincerely the numerous colleagues who read and commented on various portions of the manuscript for this and earlier editions. Their suggestions were invaluable and helped us in many ways. These include: Royce L. Abrahamson, Southwest Texas State University

- 52. Carlos J. Alsua, University of Alaska Anchorage Rabi S. Bhagat, Memphis State University Ralph R. Braithwaite, University of Hartford Stephen C. Buschardt, University of Southern Mississippi Dawn Carlson, University of Utah M. Suzzanne Clinton, Cameron University Roy A. Cook, Fort Lewis College Cynthis Cordes, State University of New York at Binghamton Aleta L. Crawford, University of Mississippi Tupelo Fred J. Dorn, University of Mississippi Julie Dziekan, University of Michigan–Dearborn Megan L. Endres, Eastern Michigan University Janice Feldbauer, Austin Community College Patricia Feltes, Southwest Missouri State University Olene L. Fuller, San Jacinto College North Richard Grover, University of Southern Maine W. Lee Grubb III, East Carolina University 28 PREFACE

- 53. Courtney Hunt, University of Delaware Ralph Katerberg, University of Cincinnati Paul N. Keaton, University of Wisconsin at LaCrosse Mary Kernan, University of Delaware Daniel Levi, California Polytechnic State University Jeffrey Lewis, Pitzer College Michael P. Lillis, Medaille College Rodney Lim, Tulane University Charles W. Mattox, Jr., St. Mary’s University Daniel W. McAllister, University of Nevada–Las Vegas James McElroy, Iowa State University Richard McKinney, Southern Illinois University Morgan R. Milner, Eastern Michigan University Linda Morable, Richland College Paula Morrow, Iowa State University Audry Murrell, University of Pittsburgh David Olsen, California State University–Bakersfield

- 54. William D. Patzig, James Madison University Shirley Rickert, Indiana University-Purdue University at Fort Wayne Roger A. Ritvo, Auburn University Montgomery David W. Roach, Arkansas Tech University Jane P. Rose, Hiram College Dr. Meshack M. Sagini, Langston University Terri A. Scandura, University of Miami, Coral Gables Holly Schroth, University of California Berkeley Marc Siegall, California State University, Chico Taggart Smith, Purdue University Patrick C. Stubbleine, Indiana University-Purdue University at Fort Wayne Paul Sweeney, Marquette University Craig A. Tunwall, SUNY Empire State College Edward Ward, St. Cloud State University Carol Watson, Rider University Philip A. Weatherford, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Richard M. Weiss, University of Delaware

- 55. Stan Williamson, University of Louisiana-Monroe Third, I wish to express appreciation to my editor, Jennifer Collins, who saw me through this project. Sometimes, it required cajoling or even threatening, but mostly her calm encouragement and constant support and direction—not to mention the patience of Job—made it possible for me to prepare this book. Editorial project manager Susie Abraham was always there to help, as was editorial assistant Meg O’Rourke. And, of course, I would be remiss in not thanking Eric Svendsen and members of the Pearson Education team for their steadfast support of this book over the years. Finally, my sincere thanks go to Pearson Education’s top-notch production team for making this book so beautiful—Kelly Warsak, project manager; Janet Slowik, art director; Suzanne DeWorken, permissions coordinator; and Sheila Norman, photo researcher; as well as Sharon Anderson at BookMasters and the staff at Integra Software Services. Their diligence and skill with the many behind-the-scenes tasks required in a book such as this one—not to mention their constant refinements—helped me immeasurably throughout the process of preparing this work. PREFACE 29 30 PREFACE It was a pleasure to work with such kind and understanding professionals, and I am greatly

- 56. indebted to them for their contributions. To all these truly outstanding individuals, and to many others too, my warm personal regards. In Conclusion: An Invitation for Feedback If you have any questions related to this book, please contact our customer service department online at http://www.247.prenhall.com. With all this behind us, now, welcome to the world of organizational behavior. Jerald Greenberg Pearson gratefully acknowledges and thanks the following people for their work on the Global Edition: Charbel N. Aoun, Lecturer, The School of Business, Lebanese American University, Lebanon Nick Barter, Research Fellow, St. Andrews Sustainability Institute and Management School, University of St. Andrews, UK Dr. Patrick K.P. Chan, Assistant Professor, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore Irene Ong Pooi Fong, Senior Lecturer, School of Marketing & Management, Division of Business & Law, Taylor’s University College, Malaysia Roger Fullwood, Associate Lecturer, Business & Management, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

- 57. Sabine Raeder, Associate Professor of Work and Organizational Psychology, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Science, University of Oslo, Norway Yusuf Sidani, Associate Professor, Management, Marketing, and Entrepreneurship Track, Olayan School of Business, American University of Beirut, Lebanon Beatrice Tan, Senior Lecturer, Centre for Innovation & Enterprise, Republic Polytechnic, Singapore Chapter Outline � Organizational Behavior: Its Basic Nature � What Are the Field’s Fundamental Assumptions? � OB Then and Now: A Capsule History � OB Responds to the Rise of Globalization and Diversity � OB Responds to Advances in Technology � OB Is Responsive to People’s Changing Expectations Learning Objectives After reading this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Define the concepts of organization and organizational

- 58. behavior. 2. Describe the field of organizational behavior’s commitment to the scientific method and the three levels of analysis it uses. 3. Trace the historical developments and schools of thought leading up to the field of organizational behavior today. 4. Identify the fundamental characteristics of the field of organizational behavior. 5. Describe how the field of organizational behavior today is being shaped by the global economy, increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the workforce, and advances in technology. 6. Explain how people’s changing expectations about the desire to be engaged in their work and the need for flexibility in work have influenced the field of organizational behavior. 31 P A R T Introduction to Organizational Behavior 1CHAPTE R 1 The Field of Organizational Behavior

- 59. 32 PART 1 • INTRODUCTION TO ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR Preview Case ■ The Talented Chief of Taleo Ask any executive to identify his or her company’smost important asset and chances are good that the response will be “people.” It’s people who keep busi- nesses alive, making it critical for human assets to be man- aged as carefully as money, inventory, or any other assets. With this in mind, most companies rely on some type of software to assist in the process of hiring, managing, developing, and compensating their employees. Tracking employee data in this fashion helps organizations keep tabs on who’s in their workforces, what they can do, and where they’re going. In the case of 46 of the Fortune 100 companies—and over 4,000 others—this process of “talent management” is entrusted to Taleo, a company of only 900 employees located in Burlingame, California. Since its inception in 1996, the company helped organizations select world-class talent by tapping into the power of the Internet. Although this hardly seems unique today, it certainly was revolution- ary back then. In those high-tech boom years, Taleo grew quickly and acquired other companies, allowing it to expand its services and to gain an international presence. Not surprisingly, however, the company faced challenges at the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century. The economy was nowhere near as robust as it was just a few years earlier, in the late 1990s. If companies aren’t hiring, the need to manage the hiring process online is

- 60. limited, leading Taleo to face a period of uncertainty. If you’re in the business of helping companies man- age people, however, then one would expect you to manage people pretty well yourself. Thanks to Taleo’s tal- ented chairman and CEO, Michael Gregoire, the company did in fact manage people effectively even during the depth of the recession in 2008. Gregoire has been cred- ited for single-handedly getting the company through a period in which its employees felt uncertain about their futures, retaining employees and clients at a time when many normally would be inclined to abandon ship. So, how exactly did Gregoire do it? Experts acknowl- edge that what saved the day was his keen understanding of the dynamics of people in organizations. He discouraged employees from dwelling on their personal uncertainties and encouraged them to focus on what the company does—service its customers by offering solid products that meet their needs. If clients inquired about the company’s problems, the sales force was armed with answers. They were completely open about what was going on behind the scenes but reassured clients that the company would be around to help them in the future. With this in mind, sales reps made it clear what Taleo is all about, describing “our value, our culture, and how we could really help them improve their company, their value, and their customers.” As Gregoire described clients, “They buy software based on the relationship you have.” And Taleo maintains outstand- ing relationships with its clients. The company’s approach to doing this involves having its sales reps help customers realize that they have problems and that Taleo could offer solutions. Because most companies weren’t hiring, it was essential

- 61. for them to keep their most talented employees from going to work at one of the few other companies that were hiring and to get as much as possible from the employees they already have. Taleo’s solution involved using the company’s products to help clients identify the skills that employees had (and that they wished to develop) and then moving them into positions that capitalize on these skills. Underutilizing resources is something that no company can afford today, and Taleo’s products help prevent this from happening. It looks like Michael Gregoire’s emphasis on transparency and emphasizing customer solutions has been successful. In the first three quarters of 2009, when most companies’ bottom lines were hemorrhaging, Taleo’s revenues grew by an eye-popping 31 percent. Gregoire believes that this is the beginning of even more impressive figures to come. We share this optimism, and not just because of the nature and quality of his company’s products. There’s something more fundamen- tal involved—Gregoire’s ability to read people. In fact, his sensitivity to the importance of build- ing relationships with customers and employees is fundamental to Taleo’s success. Gregoire appears to be aware of a key fact: No matter how good a company’s products may be, there can be no company without people. From the founder down to the lowest ranking employee, it’s all about people. If you’ve ever run or managed a business, you know that “people problems” can bring an organization down very rapidly. Hence, it makes sense to realize that people are a critical element in the effective functioning— indeed, the basic existence—of orga-

- 62. nizations. This people-centered orientation is what the field of organizational behavior (OB for short)—hence, this book—is all about. Simply put, OB is the field specializing in the study of human behavior in organizations. CHAPTER 1 • THE FIELD OF ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR 33 OB scientists and practitioners study and attempt to solve problems by using knowledge derived from research in the behavioral sciences, such as psychology and sociology. Because the field of OB is firmly rooted in science, it relies on research to derive valuable information about organizations and the complex processes operating within them. Such knowledge is used as the basis for helping to solve a wide range of organizational problems. For example, what can be done to make people more productive and more satisfied on the job? When and how should peo- ple be organized into teams? How should jobs and organizations be designed so that people best adapt to changes in the environment? These are just a few of the many important questions addressed by the field of organizational behavior. As you read this text, it will become very clear that OB specialists have attempted to learn about a wide variety of issues involving people in organizations. In fact, over the past few decades, OB has developed into a field so diverse that just about any aspect of what people do in the workplace is likely to have been examined by OB

- 63. scientists.1 The fruits of this labor already have been enjoyed by people interested in making organizations not only more productive, but also more pleasant for the individuals working in them. In the remainder of this chapter, we will give you the background information you will need to understand the scope of OB and its importance. With this in mind, this first chapter is designed to introduce you to the field of OB by focusing on its history and its fundamental characteristics. We will begin by formally defining OB, describing exactly what it is and what it seeks to accomplish. Following this, we will summarize the history of the field, tracing its roots from its origins to its emergence as a modern science. Then, in the final sections of the chapter, we will discuss the wide variety of factors that make the field of OB the vibrant, ever- changing field it is today. At this point, we will be ready to face the primary goal of this book: to enhance your understanding of the human side of work by giving you a comprehensive overview of the field of organizational behavior. Organizational Behavior: Its Basic Nature As the phrase implies, OB deals with organizations. Although you already know from experience what an organization is, a formal definition helps to avoid ambiguity. An organization is a struc- tured social system consisting of groups and individuals working together to meet some agreed- upon objectives. In other words, organizations consist of people, who alone and together in work groups strive to attain common goals. Although this definition is rather abstract, it is sure to take on more meaning as you continue reading this book. We say this

- 64. with confidence because the field of OB is concerned with organizations of all types, whether large or small in size, public or private in ownership (i.e., whether or not shares of stock are sold to the public), and whether they exist to earn a profit or to enhance the public good (i.e., nonprofit organizations, such as charities and civic groups). Regardless of the specific goals sought, the structured social units working together toward them may be considered organizations. To launch our journey through the world of OB, we will address two fundamental questions: (1) What is the field of organizational behavior all about? and (2) Why is it important to know about OB? What Is the Field of Organizational Behavior All About? The field of organizational behavior deals with human behavior in organizations. Formally defined, organizational behavior is the multidisciplinary field that seeks knowledge of behavior in organizational settings by systematically studying individual, group, and organizational processes. This knowledge is used both by scientists interested in understanding human behavior and by practitioners interested in enhancing organizational effectiveness and individual well- being. In this book we highlight both purposes by focusing on how scientific knowledge has been—or may be—used for these practical purposes. Our definition of OB highlights four central characteristics of the field. First, OB is firmly grounded in the scientific method. Second, OB studies individuals, groups, and organizations.

- 65. Third, OB is interdisciplinary in nature. And fourth, OB is used as the basis for enhancing orga- nizational effectiveness and individual well-being. We will now take a closer look at these four characteristics of the field. organization A structured social system consisting of groups and individuals working together to meet some agreed-upon objectives. organizational behavior The field that seeks to understand individual, group, and organizational processes in the workplace. 34 PART 1 • INTRODUCTION TO ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR OB APPLIES THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD TO PRACTICAL MANAGERIAL PROBLEMS. In our definition of OB, we refer to seeking knowledge and to studying behavioral processes. This should not be surprising since, as we noted earlier, OB knowledge is based on the behavioral sciences. These are fields such as psychology and sociology that seek knowledge of human behavior and society through the use of the scientific method. Although not as sophisticated as many of the “hard sciences,” such as physics or chemistry—nor as mature as

- 66. them—OB’s orientation is still scien- tific in nature. Thus, like other scientific fields, OB seeks to develop a base of knowledge by using an empirical, research-based approach. That is, it is based on systematic observation and measure- ment of the behavior or phenomenon of interest. As we will describe in Appendix 1, organiza- tional research is neither easy nor foolproof. After all, both people and organizations are quite complex, making it challenging sometimes to get a handle on understanding them. It is widely agreed that the scientific method is the best way to learn about behavior in organizations. For this reason, the scientific orientation should be acknowledged as a hallmark of the field of OB. As they seek to improve organizational functioning and the quality of life of people working in organizations, managers rely heavily on knowledge derived from OB research. For example, researchers have shed light on such practical questions as: � How can goals be set to enhance people’s job performance? � How can jobs be designed to enhance employees’ feelings of satisfaction? � Under what conditions do individuals make better decisions than groups? � What can be done to improve the quality of organizational communication? � What steps can be taken to alleviate work-related stress? � What do leaders do to enhance the effectiveness of their teams? � How can organizations be designed to make people highly productive? Throughout this book we will describe scientific research and

- 67. theory bearing on the answers to these and dozens of other practical questions. It is safe to say that the scientific and applied facets of OB not only coexist, but complement one another. Indeed, just as knowledge about the properties of physics may be put to use by engineers, and engineering data can be used to test theories of basic physics, so too are knowledge and practical applications closely intertwined in the field of OB. OB FOCUSES ON THREE LEVELS OF ANALYSIS— INDIVIDUALS, GROUPS, AND ORGANIZATIONS. To best appreciate behavior in organizations, OB specialists cannot focus exclusively on individuals acting alone. After all, in organizations people frequently work together in groups and teams. Furthermore, people—alone and in groups—both influence and are influenced by their work envi- ronments. Considering this, it should not be surprising to learn that the field of OB focuses on three distinct levels of analysis—individuals, groups, and organizations (see Figure 1.1). The field of OB recognizes that all three levels of analysis must be considered to comprehend fully the complex dynamics of behavior in organizations. Careful attention to all three levels of analysis—and the relationships between them—is a central theme in modern OB, and this will be reflected fully throughout this text. For example, we will be describing how OB scientists are con- cerned with individual perceptions, attitudes, and motives. We also will be describing how people communicate with each other and coordinate their activities among themselves in work groups.

- 68. Finally, we will examine organizations as a whole—the way they are structured and operate in their environments, and the effects of their operations on the individuals and groups within them. OB IS MULTIDISCIPLINARY IN NATURE. When you consider the broad range of issues and approaches that the field of OB encompasses, it is easy to appreciate the fact that the field is multidisciplinary in nature. By this, we mean that it draws on a wide variety of social science disciplines. Rather than studying a topic from only one particular perspective, the field of OB is likely to consider a wide variety of approaches. These range from the highly individual-oriented approach of psychology, through the more group-oriented approach of sociology, to issues in organizational quality studied by management scientists. For a summary of some of the key fields from which OB draws, see Table 1.1. If, as you read this book, you recognize some particular theory or approach as familiar, chances are good that you may have learned something about it in another class. What makes OB so special is that it combines these various orientations together into a single field, one that’s very broad and exciting. behavioral sciences Fields such as psychology and sociology that seek knowledge of human behavior and society through the use of the scientific method.

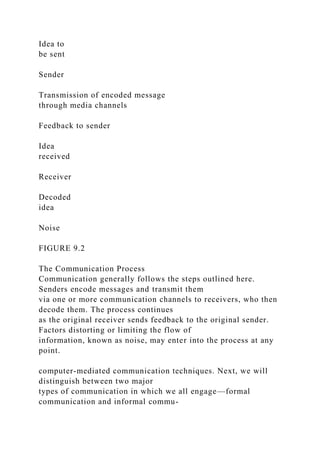

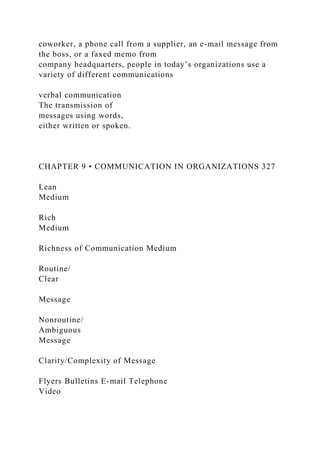

- 69. CHAPTER 1 • THE FIELD OF ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR 35 TABLE 1.1 The Multidisciplinary Roots of OB Specialists in OB derive knowledge from a wide variety of social science disciplines to create a unique, multidisciplinary field. Some of the most important parent disciplines are listed here, along with some of the OB topics to which they are related (and the chapters in this book in which they are discussed). Discipline Relevant OB Topics Psychology Perception and learning (Chapter 3); personality (Chapter 4); emotion and stress (Chapter 5); attitudes (Chapter 6); motivation (Chapter 7); decision making (Chapter 10); creativity (Chapter 14) Sociology Group dynamics (Chapter 8); teamwork (Chapter 8); communication (Chapter 9) Anthropology Organizational culture (Chapter 14); leadership (Chapter 13) Political science Interpersonal conflict (Chapter 11); organizational power (Chapter 12) Economics Decision making (Chapter 10); negotiation (Chapter 11); organizational power (Chapter 12) Management science Organizational structure (Chapter 15); organizational change (Chapter 16)