Haematuria

- 2. INTRODUCTION Haematuria is defined as presence of more than 5 RBCs per microliter of urine. Normal children can excrete more than 500,000 RBCs per 24hrs. Increased amount in fever and exercise. Can be detected by microscopy or dipstick method. Uses a peroxidase reaction to create a colour change It can detect 3-5 RBCs/uL of unspun urine. Clinically significant haematuria is when >50 RBCs/uL.

- 3. False (+)se- Haemoglobinuria. Myoglobinuria. Presence of microbial peroxidases as in UTIs. Alkaline urine(pH >8). Hydrogen peroxide used to clean perineum. False (-)se- Presence of Formalin(used as a preservative). Ascorbic acid in high doses(>2000mg/day)

- 4. CONDITIONS THAT MIMIK HAEMATURIA Haem (+)-Haemoglobin, Myoglobin Haem (-)-Drugs(Chloroquine, Desferioxamin, Metronidazole, Rifampicin) Dyes(Beet, Colouring) Metabolites(Homogentisic acid, Melanin, Methemoglobin, Porphyrin. Urates)

- 9. IGA NEPHROPATHY(BERGER’S DISEASE) Most common chronic glomerular disease in children. Predominant IgA in mesangial glomerular deposits. Associated with mesangial proliferation and increased mesangial matrix Immune complex disease initiated by excessive amounts of poorly galactosylated IgA1 in the serum Production of IgG and IgA autoantibodies. Also been observed in patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Hypothesis that these 2 diseases are part of the same disease spectrum.

- 10. Familial clustering of IgA nephropathy cases suggests the importance of genetic factors. CLINICAL AND LABORATORY MANIFESTATIONS More often in male than in female patients. Clinical presentation in childhood is often benign in comparison to that of adults. Uncommon cause of end-stage renal failure during childhood. Presentations include acute nephritic syndrome, nephrotic syndrome, or a combined nephritic-nephrotic picture. Gross haematuria often occurs within 1-2 days of onset of an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. May be associated with loin pain. Proteinuria is often <1000 mg/24 hr in patients with asymptomatic microscopic haematuria.

- 11. Mild to moderate hypertension is most often seen in patients with nephritic or nephrotic syndrome. Normal serum levels of C3 in IgA nephropathy. Serum IgA levels have no diagnostic value because they are elevated in only 15% of paediatric patients. PROGNOSIS AND TREATMENT Does not lead to significant kidney damage in most children. Progressive disease develops in 20-30% of patients 15-20 yrs. after disease onset. Poor prognostic indicators at presentation or follow-up include, Hypertension, diminished renal function, and significant, increasing or prolonged proteinuria

- 12. More severe prognosis is correlated with histologic evidence of diffuse mesangial proliferation, extensive glomerular crescents, glomerulosclerosis, and diffuse tubulointerstitial changes, including inflammation and fibrosis. TREATMENT Appropriate BP control and management of significant proteinuria. ACE inhibitors and ARBs are effective in reducing proteinuria and retarding the rate of disease progression. Fish oil, which contains anti-inflammatory omega-3 PUFAs, may decrease the rate of disease progression in adults. Corticosteroids reduce proteinuria and improve renal function in those patients with a glomerular filtration rate >60 mL/min/m2. Additional immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide or azathioprine has not appeared to be effective.

- 13. Performing a tonsillectomy in the absence of significant tonsillitis in association with IgA nephropathy is currently not recommended. Patients with IgA nephropathy may undergo successful kidney transplantation. Recurrent disease is frequent, allograft loss caused by IgA nephropathy occurs in only 15-30% of patients.

- 14. ALPORT SYNDROME Caused by mutations in the genes coding for type IV collagen. Major component of basement membranes. GENETICS 85% of patients have X-linked inheritance. Mutation in the COL4A5 gene encoding the α5 chain of type IV collagen. Autosomal recessive forms of AS are caused by mutations in the COL4A3 and COL4A4 genes on chromosome 2 encoding the α3 and α4 chains of type IV collagen.

- 15. Autosomal dominant form of AS linked to the COL4A3-COL4A4 gene locus occurs in 5% of cases. PATHOLOGY In most patients, electron microscopy reveals diffuse thickening, thinning, splitting, and layering of the glomerular and tubular basement membranes. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS All patients with AS have asymptomatic microscopic haematuria. Gross haematuria commonly occurring 1-2 days after an upper respiratory infection are seen in approximately 50% of patients. Proteinuria is often seen in boys. May be absent, mild, or intermittentin girls.

- 16. Progressive proteinuria, often exceeding 1 g/24 hr, is common by the 2nd decade of life and can be severe enough to cause nephrotic syndrome. Bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, which is never congenital, develops in 90% of hemizygous males with X-linked AS, 10% of heterozygous females with X-linked AS. Ocular abnormalities in 30-40% with X-linked AS, include anterior lenticonus, macular flecks, and corneal erosions. Leiomyomatosis of the oesophagus, tracheobronchial tree, and female genitals in association with platelet abnormalities has been reported, but is rare.

- 17. DIAGNOSIS Family history, a screening urinalysis of 1stdegree relatives, an audiogram, an ophthalmologic examination are critical in making the diagnosis. Anterior lenticonus is pathognomonic. Highly likely in the patient who has haematuria and at least 2 of the Macular flecks, recurrent corneal erosions, GBM thickening and thinning, or sensorineural deafness. Absence of epidermal basement membrane staining for the α5 chain of type IV collagen in male hemizygotes, Discontinuous epidermal basement membrane staining in female heterozygotes on skin biopsy is pathognomonic for X-linked AS. Genetic testing is clinically available for X-linked AS and COL4A5 mutations.

- 18. Prenatal diagnosis is available for families with members who have X-linked AS and who carry an identified mutation. PROGNOSIS AND TREATMENT Risk of progressive renal dysfunction leading to ESRD is highest among hemizygotes and autosomal recessive homozygotes. Occurs before age 30 yr in approximately 75% of hemizygotes with X-linked AS. Risk of ESRD in X-linked heterozygotes is 12% by age 40 yr and 30% by age 60 yr. Risk factors for progression are, Gross haematuria during childhood, nephrotic syndrome, and prominent GBM thickening. No specific therapy is available to treat.

- 19. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, can slow the rate of progression. Mx of renal failure complications such as hypertension, anaemia, and electrolyte imbalance is critical. ESRD is treated with dialysis and kidney transplantation. 5% of kidney transplantation recipients develop anti-GBM nephritis, It occurs primarily in males with X-linked AS who develop ESRD before age 30 yr. Pharmacologic treatment of proteinuria with ACE inhibition or ARB has shown promise in AS. Screening of heterozygote carriers for significant renal disease in later adulthood.

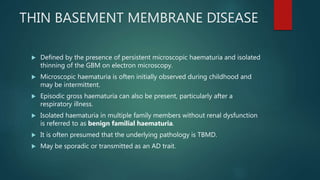

- 20. THIN BASEMENT MEMBRANE DISEASE Defined by the presence of persistent microscopic haematuria and isolated thinning of the GBM on electron microscopy. Microscopic haematuria is often initially observed during childhood and may be intermittent. Episodic gross haematuria can also be present, particularly after a respiratory illness. Isolated haematuria in multiple family members without renal dysfunction is referred to as benign familial haematuria. It is often presumed that the underlying pathology is TBMD. May be sporadic or transmitted as an AD trait.

- 21. Heterozygous mutations in the COL4A3 and COL4A4 genes, which encode the α3 and α4 chains of type IV collagen present in the GBM. Rare cases of TBMD progress, and develop significant proteinuria, hypertension, or renal insufficiency. Homozygous mutations in these same genes result in AR AS. Absence of a positive family history for renal insufficiency or deafness would not necessarily predict a benign outcome. Monitoring patients with benign familial haematuria for progressive proteinuria, hypertension, or renal insufficiency is important through childhood and young adulthood.

- 25. GOODPASTURE DISEASE Characterized by pulmonary haemorrhage and glomerulonephritis. antibodies directed against certain epitopes of type IV collagen, located within the alveolar basement membrane in the lung and glomerular basement membrane (GBM) in the kidney. PATHOLOGY Crescentic glomerulonephritis in most patients. Immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrates continuous linear deposition of immunoglobulin G along the GBM

- 26. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Rare in childhood. Usually present with haemoptysis from pulmonary haemorrhage that can life-threatening. Renal manifestations include acute glomerulonephritis with haematuria, proteinuria, and hypertension, which usually follows a rapidly progressive course. Renal failure commonly develops within days to weeks of presentation. Uncommonly, patients can have isolated, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis without pulmonary haemorrhage. In all cases, serum anti-GBM antibody is present and complement C3 level is normal. In patients who have Ant neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody levels elevated along with the anti-GBM antibody have severe prognosis.

- 27. DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Dx is made by a combination of the clinical presentation of pulmonary haemorrhage with AGN, The presence of antibodies against GBM), and characteristic renal biopsy findings. DDx are systemic lupus erythematosus, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Nephrotic syndrome–associated pulmonary embolism, and microscopic polyangiitis.

- 28. PROGNOSIS AND TREATMENT Untreated, the prognosis of Goodpasture disease is poor. High-dose IV methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide,and plasmapheresis appears to improve survival. Patients who survive the pulmonary hemorrhage often progress to end- stagerenal failure despite ongoing immunosuppressive therapy.

- 29. HENOCH-SCHÖNLEIN PURPURA NEPHRITIS The most common small vessel vasculitis in childhood. Characterized by a purpuric rash and accompanied by arthritis and abdominal pain. 50% of patients with HSP develop renal manifestations, It varies from asymptomatic microscopic haematuria to severe, progressive glomerulonephritis.

- 30. PATHOGENESIS AND PATHOLOGY Mediated by the deposition of polymeric immunoglobulin A (IgA) in glomeruli. Analogous to the same type of IgA deposits seen in systemic small vessels, Findings can be indistinguishable from those of IgA nephropathy. CLINICAL AND LABORATORY MANIFESTATIONS Nephritis associated with HSP usually follows onset of the rash. Weeks or even months after the initial presentation of the disease. Only rarely before onset of the rash. Most patients have only mild renal manifestations, isolated microscopic haematuria without significant proteinuria.

- 31. INTRODUCTION A common cause of community acquired acute kidney injury in children. Several sub-types Infection induced Genetic Medication-induced Systemic disease associated Classical triad of MAHA, Thrombocytopenia and Renal insufficiency HAEMOLYTIC UREMIC SYNDROME

- 32. Etiology Commonest cause- Diarrhoea associated HUS with STEC E.coli in western countries and Shigella dysenteriae type 1 in Asia and south Africa. Several serotypes of E.coli O157:H7 and O104:H4 Reservoir is GI tract of animals. Transmitted by eating undercooked meat and drinking unpasteurised milk Rarely can be associated with Empyema. It is due to neuraminidase providing Streptococcus pneumonia. Similar type of disease occurs in HIV

- 33. Genetic forms of HUS can be associated with Deficiencies of Von willibrand factor cleaving protease (ADAMTS13) or complement factors H,I and B and Vitamin B12 metabolism. Absent prodromal diarrhoea. Relapsing non-remitting course. HUS can occur with illnesses that cause microvascular injury Eg:-Malignant Hypertension, SLE, Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome Iatrogenic causes:- Bone marrow transplant, calcineurin inhibitors etc.

- 34. Pathogenesis Microvascular injury with endothelial damage. Toxins cause direct endothelial damage Shiga toxin promote platelet aggregation. Neuraminidase cleaves sialic acid on endothelial cells, RBC and platelets to expose Thomson-Freidenreich (T) antigen Microvascular injury is triggered by endogenous IgM Familial cases inherited deficiencies of inhibitors of complement pathway causing a cascade of cellular injury.

- 35. Micro thrombi in kidney causing decrease GFR Platelet aggregation causes consumptive thrombocytopenia Micoangiopathic haemolytic anaemia is caused by mechanical damage to RBC when they pass through damaged and thrombosed microvasculature

- 36. Clinical Manifestations Most common in preschool and school age children. In infection associated HUS, starts after an episode of diarrhoea. Often bloody, but doesn't necessary to be Oliguria can be masked by ongoing diarrhoea. Can present with volume overload or dehydration.

- 37. Pneumonia associated HUS may begin with predominant lung signs. Genetic variants are insidious. Can become a severe multisystemic disease No significant factors to predict the outcome at the onset of the disease. Renal dysfunction and haemolysis can lead to sever hyperkalaemia Severe anaemia, volume overload and hypertension can cause heart failure

- 38. Heart involvement with pericarditis myocarditis and arrhythmias can occur independent of electrolyte imbalances and volume overload. CNS involvement with irritability lethargy and seizures can occur in <20%. Encephalopathy and seizures can occur. Focal ischemia and small infarction in basal ganglia are reported. Large infarctions and intracranial haemorrhages are rare. GI complications can occur such as inflammatory colitis, bowel perforations, intussusception and pancreatitis. Petechiae can develop but overt haemorrhage is rare.

- 39. Diagnosis Classic triad of MAHA Thrombocytopenia and renal insufficiency Anaemia can progress very rapidly. Thrombocytopenia may be variable with range of 20,000-100,000 PT and APTT will be normal. Coombs test is negative except in Neuraminidase induced HUS. Urine analysis will show haematuria and low grade proteinuria.

- 40. Renal functions will be elevated. Most often stool cultures and full reports do not become positive. Kidney Bx is rarely indicated. If no history of prodromal diarrhoea or chest infection is noted, evaluation should be done for genetic forms. Other forms of microangiopathy should also be excluded.

- 41. Prognosis Death risk is <5%. Most recover completely. 5% remain depended on dialysis. 30% is left with some chronic renal insufficiency. HUS not associated with diarrhoea is more severe. Pneumococcal associated HUS has a high morbidity and a mortality approaching 20%

- 42. Familial or genetic forms have a relapsing course with poor prognosis.

- 43. Management Management is supportive. Includes fluid and electrolyte management control of hypertension and management of complications. Early volume expansion may be nephron-protective in diarrhoea associated HUS. Red cell transfusion is recommended until the acute phase of the illness is over.

- 44. In pneumococcal associated HUS red cells should be washed prior to transfusion. If not endogenous IgM may react with exposed T Ag

- 45. Platelets need not be administered as they are consumed quickly and can cause thrombi formation. Antibiotic therapy can worsen the disease course in diarrhoea associated HUS. But prompt treatment should be given for pneumococcal associated HUS. Plasma paresis has been proposed for patients with severe involvement specially CNS involvement It is contraindicated in Pneumococcal associated HUS.

- 46. Eculizumab (ant C5 Ab) is used to treat atypical HUS It inhibits complement pathway. No significance in diarrhoea associated HUS. Increase in risk for meningitis- Meningococcal vaccination is done for all who are treated. Plasma exchange is recommended for patients with ADAMTS13 or factor H deficiencies.

- 47. OTHER UPPER TRACT CAUSES OF HAEMATURIA Interstitial Nephritis Toxic Nephropathy Cortical Necrosis Pyelonephritis Nephrocalcinosis Vascular Abnormalities- Haemangiomas, haemangiolymphangiomas, angiomyomas, and arteriovenous malformations of the kidneys and lower urinary tract are rare causes of haematuria.

- 48. Nutcracker syndrome Unilateral bleeding of varicose veins of the left ureter, Resulting from compression of the left renal vein between the aorta and superior mesenteric artery (mesoaortic compression). Typically present with persistent microscopic haematuria ,recurrent gross haematuria. It may be accompanied by proteinuria, left lower abdominal pain, left flank pain, or orthostatic hypotension. Diagnosis requires a high degree of suspicion and is confirmed by Doppler ultrasonography, CT, phlebography of the left renal vein, or magnetic resonance angiography.

- 49. RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS Occurs in 2 distinct clinical settings. In newborns and infants, RVT is commonly associated with asphyxia, dehydration, shock, sepsis, congenital hypercoagulable states, maternal diabetes In older children, Patients with nephrotic syndrome, cyanotic heart disease, inherited hypercoagulable states, sepsis, following kidney transplantation, and following exposure to angiographic contrast agents.

- 50. PATHOGENESIS Begins in the intrarenal venous circulation and can then extend to the main renal vein and IVC. Mediated by endothelial cell injury resulting from hypoxia, endotoxin, or contrast media hypercoagulability from nephrotic syndrome, factor V Leiden deficiency, hypovolemia, septic shock, dehydration, intravascular sludging caused by polycythaemia. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Sudden onset of gross haematuria and unilateral or bilateral flank masses. Can also present with microscopic haematuria, flank pain, hypertension, or a MAHA with thrombocytopenia or oliguria.

- 51. DIAGNOSIS Suggested by the development of haematuria and flank masses in patients seen in the high-risk clinical settings. USS shows marked renal enlargement, and radionuclide studies reveal little no renal function in the affected kidney. Doppler studies of the IVC and renal vein confirm the diagnosis. TREATMENT Aggressive supportive intensive care, including correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalance and Rx of renal insufficiency. Rx of BL RVT should include tissue plasminogen activator and unfractionated heparin followed by continued anticoagulation with unfractionated or low- molecular-weight heparin

- 52. Children with severe HTN secondary to RVT refractory to antihypertensives may require nephrectomy. PROGNOSIS Partial or complete renal atrophy is a common sequela of RVT in the neonate. Increased risk of renal insufficiency, renal tubular dysfunction, and systemic HTN. Recovery of renal function is not uncommon in older children with correction of the underlying etiology.

- 53. IDIOPATHIC HYPERCALCIURIA May be inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder, May present as, Recurrent gross hematuria, persistent microscopic hematuria, dysuria, or abdominal pain in the absence of stone formation. DIAGNOSIS 24 hr urinary calcium excretion >4 mg/kg. A screening test for may be performed on a random urine specimen by measuring the calcium and creatinine concentrations.

- 54. Spot urine calcium : creatinine ratio (mg/dL : mg/dL) >0.2 suggests hypercalciuria in an older child. Normal ratios may be as high as 0.8 in infants <7 mo of age. TREATMENT Left untreated, hypercalciuria leads to nephrolithiasis in 15%. Increased risk for development of low bone mineral density as well as an increased incidence of UTI. Risk factor in 40% of children with kidney stones. Low urinary citrate level has been associated as a risk factor in approximately 38%. thiazide diuretics can normalize urinary calcium excretion by stimulating calcium reabsorption in the proximal and distal tubules.

- 55. Leads to resolution of gross haematuria or dysuria and can prevent nephrolithiasis. In persistent gross haematuria or dysuria, HTC at a dose of 1-2 mg/kg/24 hr as a single morning dose. Dose is titrated upward until the 24 hr urinary calcium excretion is <4 mg/kg After 1 yr of treatment, hydrochlorothiazide is usually discontinued, Resumed if gross haematuria, nephrolithiasis, or dysuria recurs. Serum potassium level should be monitored periodically to avoid hypokalaemia. Potassium citrate at a dose of 1 mEq/kg/24 hr may also be beneficial, In patients with low urinary citrate excretion and symptomatic dysuria. Na restriction is important because urinary Ca excretion parallels Na excretion excretion

- 56. Leads to resolution of gross haematuria or dysuria and can prevent nephrolithiasis. In persistent gross haematuria or dysuria, HTC at a dose of 1-2 mg/kg/24 hr as a single morning dose. Dose is titrated upward until the 24 hr urinary calcium excretion is <4 mg/kg After 1 yr of treatment, hydrochlorothiazide is usually discontinued, Resumed if gross haematuria, nephrolithiasis, or dysuria recurs. Serum potassium level should be monitored periodically to avoid hypokalaemia. Potassium citrate at a dose of 1 mEq/kg/24 hr may also be beneficial, In patients with low urinary citrate excretion and symptomatic dysuria. Na restriction is important because urinary Ca excretion parallels Na excretion excretion

- 57. dietary Ca restriction is not recommended (except in children with massive Ca intake >250% of RDA by dietary history) Ca is a critical requirement for growth, No evidence supports a relationship between decreased Ca intake and decreased urinary Ca levels. Bisphosphonate therapy, which leads to a reduction in urinary calcium excretion and improvement in bone mineral density. (Further studies are needed to prove efficacy)

- 58. HEMATOLOGIC DISEASES CAUSING HAEMATURIA SICKLE CELL NEPHROPATHY Gross or microscopic haematuria may be seen in children with sickle cell disease or sickle trait Hematuria tends to resolve spontaneously in the majority Related to microthrombosis secondary to sickling Clinical manifestations of SSN include polyuria caused by a urinary concentrating defect, renal tubular acidosis, and proteinuria Tubular manifestations have no specific treatment Can lead to hypertension, renal insufficiency, and kidney failure

- 59. AUTOSOMAL RECESSIVE POLYCYSTIC KIDNEY DISEASE Referred to as infantile polycystic disease Gene for ARPKD (PKHD1 [polycystic kidney and hepatic disease]) encodes fibrocystin PATHOLOGY Both kidneys are markedly enlarged and show innumerable cysts throughout the cortex and medulla Progressive interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy during advanced stages of disease dual-organ disease and should be considered as ARPKD/congenital hepatic fibrosis

- 60. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS BL flank masses during the neonatal period or in early infancy. May associate with oligohydramnios, pulmonary hypoplasia, respiratory distress, and spontaneous pneumothorax in the neonatal period. Potter syndrome including low-set ears, micrognathia, flattened nose, limb positioning defects, and intrauterine growth restriction, may be present at death from pulmonary hypoplasia. HTN noted within the first few weeks of life Severe requires aggressive multidrug therapy ARF uncommon 50% of patients with a neonatal-perinatal presentation develop ESRD by age 10 yr.

- 61. increasingly recognized in infants with a mixed renal-hepatic clinical picture Hepatic disease -portal hypertension, hepatosplenomegaly, gastroesophageal varices, ascending cholangitis, prominent cutaneous periumbilical veins, reversal of portal vein flow, and thrombocytopenia Renal findings in range from asymptomatic abnormal renal ultrasonography to systemic HTN and renal insufficiency. Radiologic or clinical laboratory assessment is present in approximately 45% Universal by microscopic evaluation.

- 62. DIAGNOSIS Markedly enlarged and uniformly hyperechogenic kidneys with poor corticomedullary differentiation on ultrasonography Supported by clinical and laboratory signs of hepatic fibrosis, Findings of ductal plate abnormalities seen on liver biopsy, Anatomic and pathologic proof of ARPKD in a sibling, or parental consanguinity Confirmed by genetic testing TREATMENT Supportive . Aggressive ventilator support is often necessary in the neonatal period

- 63. management of hypertension-ACE inhibitors Fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, Osteopenia , Manifestations of renal insufficiency Pt with severe respiratory failure or feeding intolerance from enlarged kidneys can require unilateral or bilateral nephrectomies Dual renal and hepatic transplantation Avoids the later development of end-stage liver disease despite successful renal transplantation

- 64. PROGNOSIS 30% die in the neonatal period from complications of pulmonary hypoplasia. Increased 10 yr survival of children surviving beyond the1st yr of life to >80%. Fifteen-year survival is currently estimated at 70-80%

- 65. AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT POLYCYSTIC KIDNEY DISEASE The commonest hereditary human kidney disease, Systemic disorder Possible cyst formation in multiple organs (liver, pancreas, spleen, brain) Development of saccular cerebral aneurysms PATHOLOGY Both kidneys are enlarged and show cortical and medullary cysts originating from all regions of the nephron.

- 66. 85% Mutations that map to the PKD1 gene on the short arm of chromosome 16, Which encodes polycystin, a transmembrane glycoprotein 10-15% of mutations map to the PKD2 gene on the long arm of chromosome 4, which encodes polycystin 2, a proposed nonselective cation channel Mutations can be found in 85% of patients 8-10% will have de novo mutations Mutations of PKD1 are associated with more severe renal disease than mutations of PKD2

- 67. CLINICAL PRESENTATION Symptomatic ADPKD commonly occurs in the 4th or 5th decade. Gross or microscopic Hematuria, bilateral flank pain, abdominal masses, hypertension, and urinary tract infection, may be seen in neonates, children,and Most are diagnosed by abnormal renal sonography in the absence of symptoms. Multiple bilateral macrocysts +/- enlarged kidneys Cysts may be asymptomatic but present within the liver, pancreas, spleen, and ovaries Intracranial aneurysms, which appear to segregate within certain families, have an overall prevalence of 15%

- 68. MVP is seen in approximately 12% of children; Hernias, bronchiectasis, and intestinal diverticula can also occur in these children. DIAGNOSIS Enlarged kidneys with B/L macrocysts in a patient with an affected 1st-degree relative. Parental renal sonography an important diagnostic test to be performed in families with no apparent family history. Prenatal diagnosis is suggested from the presence of enlarged kidneys with or without cysts on ultrasonography In families with known ADPKD. Prenatal DNA testing is available

- 69. TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS Primarily supportive. BP Control is critical Rate of disease progression in ADPKD correlates with the presence of HTN ACEI or ARB are Rx of choice. Obesity, caffeine ingestion, smoking, multiple pregnancies,male gender, and possibly the use of calcium channel blockers appear to accelerate progression Neonatal ADPKD may be fatal ADPKD that occurs initially in older children has a favourable prognosis, Normal renal function during childhood seen in >80%of children.

- 70. LOWER URINARY TRACT CAUSES OF HEMATURIA Urethritis Exercise Haemorrhagic Cystitis Presence of sustained Hematuria and LUTS in the absence of other bleeding conditions or a bacterial urinary tract infection. Can occur in response to chemical toxins (cyclophosphamide, penicillins, dyes, insecticides), viruses (adenovirus types 11 and 21 and influenza A), radiation, and amyloidosis

- 71. Treatment consists of a combination of intensive hydration, forced diuresis, analgesia, and spasmolytic drugs Haematuria associated with viral haemorrhagic cystitis usually resolves within 1 wk.

- 73. THANK YOU !

![AUTOSOMAL RECESSIVE POLYCYSTIC

KIDNEY DISEASE

Referred to as infantile polycystic disease

Gene for ARPKD (PKHD1 [polycystic kidney and hepatic disease]) encodes

fibrocystin

PATHOLOGY

Both kidneys are markedly enlarged and show innumerable cysts

throughout the cortex and medulla

Progressive interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy during advanced

stages of disease

dual-organ disease and should be considered as ARPKD/congenital

hepatic fibrosis](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/haematuria-200610163415/85/Haematuria-59-320.jpg)