Programming language design_concepts

- 2. PROGRAMMING LANGUAGE DESIGN CONCEPTS

- 4. PROGRAMMING LANGUAGE DESIGN CONCEPTS David A. Watt, University of Glasgow with contributions by William Findlay, University of Glasgow

- 5. Copyright 2004 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (+44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): cs-books@wiley.co.uk Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system for exclusive use by the purchase of the publication. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to permreq@wiley.co.uk, or faxed to (+44) 1243 770620. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. ADA is a registered trademark of the US Government Ada Joint Program Office. JAVA is a registered trademark of Sun Microsystems Inc. OCCAM is a registered trademark of the INMOS Group of Companies. UNIX is a registered trademark of AT&T Bell Laboratories. Other Wiley Editorial Offices John Wiley & Sons Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA Jossey-Bass, 989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741, USA Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Boschstr. 12, D-69469 Weinheim, Germany John Wiley & Sons Australia Ltd, 33 Park Road, Milton, Queensland 4064, Australia John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2 Clementi Loop #02-01, Jin Xing Distripark, Singapore 129809 John Wiley & Sons Canada Ltd, 22 Worcester Road, Etobicoke, Ontario, Canada M9W 1L1 Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Watt, David A. (David Anthony) Programming language design concepts / David A. Watt ; with contributions by William Findlay. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-470-85320-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Programming languages (Electronic computers) I. Findlay, William, 1947- II. Title. QA76.7 .W388 2004 005.13 – dc22 2003026236 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-470-85320-4 Typeset in 10/12pt TimesTen by Laserwords Private Limited, Chennai, India Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, King’s Lynn This book is printed on acid-free paper responsibly manufactured from sustainable forestry in which at least two trees are planted for each one used for paper production.

- 6. To Carol

- 8. Contents Preface xv Part I: Introduction 1 1 Programming languages 3 1.1 Programming linguistics 3 1.1.1 Concepts and paradigms 3 1.1.2 Syntax, semantics, and pragmatics 5 1.1.3 Language processors 6 1.2 Historical development 6 Summary 10 Further reading 10 Exercises 10 Part II: Basic Concepts 13 2 Values and types 15 2.1 Types 15 2.2 Primitive types 16 2.2.1 Built-in primitive types 16 2.2.2 Defined primitive types 18 2.2.3 Discrete primitive types 19 2.3 Composite types 20 2.3.1 Cartesian products, structures, and records 21 2.3.2 Mappings, arrays, and functions 23 2.3.3 Disjoint unions, discriminated records, and objects 27 2.4 Recursive types 33 2.4.1 Lists 33 2.4.2 Strings 35 2.4.3 Recursive types in general 36 2.5 Type systems 37 2.5.1 Static vs dynamic typing 38 2.5.2 Type equivalence 40 2.5.3 The Type Completeness Principle 42 2.6 Expressions 43 2.6.1 Literals 43 2.6.2 Constructions 44 2.6.3 Function calls 46 2.6.4 Conditional expressions 47 2.6.5 Iterative expressions 48 2.6.6 Constant and variable accesses 49 vii

- 9. viii Contents 2.7 Implementation notes 49 2.7.1 Representation of primitive types 49 2.7.2 Representation of Cartesian products 50 2.7.3 Representation of arrays 50 2.7.4 Representation of disjoint unions 51 2.7.5 Representation of recursive types 51 Summary 52 Further reading 52 Exercises 52 3 Variables and storage 57 3.1 Variables and storage 57 3.2 Simple variables 58 3.3 Composite variables 59 3.3.1 Total vs selective update 60 3.3.2 Static vs dynamic vs flexible arrays 61 3.4 Copy semantics vs reference semantics 63 3.5 Lifetime 66 3.5.1 Global and local variables 66 3.5.2 Heap variables 68 3.5.3 Persistent variables 71 3.6 Pointers 73 3.6.1 Pointers and recursive types 74 3.6.2 Dangling pointers 75 3.7 Commands 77 3.7.1 Skips 77 3.7.2 Assignments 77 3.7.3 Proper procedure calls 78 3.7.4 Sequential commands 79 3.7.5 Collateral commands 79 3.7.6 Conditional commands 80 3.7.7 Iterative commands 82 3.8 Expressions with side effects 85 3.8.1 Command expressions 86 3.8.2 Expression-oriented languages 87 3.9 Implementation notes 87 3.9.1 Storage for global and local variables 88 3.9.2 Storage for heap variables 89 3.9.3 Representation of dynamic and flexible arrays 90 Summary 91 Further reading 91 Exercises 92 4 Bindings and scope 95 4.1 Bindings and environments 95 4.2 Scope 97

- 10. Contents ix 4.2.1 Block structure 97 4.2.2 Scope and visibility 99 4.2.3 Static vs dynamic scoping 100 4.3 Declarations 102 4.3.1 Type declarations 102 4.3.2 Constant declarations 104 4.3.3 Variable declarations 104 4.3.4 Procedure definitions 105 4.3.5 Collateral declarations 105 4.3.6 Sequential declarations 106 4.3.7 Recursive declarations 107 4.3.8 Scopes of declarations 108 4.4 Blocks 108 4.4.1 Block commands 109 4.4.2 Block expressions 110 4.4.3 The Qualification Principle 110 Summary 111 Further reading 112 Exercises 112 5 Procedural abstraction 115 5.1 Function procedures and proper procedures 115 5.1.1 Function procedures 116 5.1.2 Proper procedures 118 5.1.3 The Abstraction Principle 120 5.2 Parameters and arguments 122 5.2.1 Copy parameter mechanisms 124 5.2.2 Reference parameter mechanisms 125 5.2.3 The Correspondence Principle 128 5.3 Implementation notes 129 5.3.1 Implementation of procedure calls 130 5.3.2 Implementation of parameter mechanisms 130 Summary 131 Further reading 131 Exercises 131 Part III: Advanced Concepts 133 6 Data abstraction 135 6.1 Program units, packages, and encapsulation 135 6.1.1 Packages 136 6.1.2 Encapsulation 137 6.2 Abstract types 140 6.3 Objects and classes 145 6.3.1 Classes 146 6.3.2 Subclasses and inheritance 151

- 11. x Contents 6.3.3 Abstract classes 157 6.3.4 Single vs multiple inheritance 160 6.3.5 Interfaces 162 6.4 Implementation notes 164 6.4.1 Representation of objects 164 6.4.2 Implementation of method calls 165 Summary 166 Further reading 167 Exercises 167 7 Generic abstraction 171 7.1 Generic units and instantiation 171 7.1.1 Generic packages in ADA 172 7.1.2 Generic classes in C++ 174 7.2 Type and class parameters 176 7.2.1 Type parameters in ADA 176 7.2.2 Type parameters in C++ 180 7.2.3 Class parameters in JAVA 183 7.3 Implementation notes 186 7.3.1 Implementation of ADA generic units 186 7.3.2 Implementation of C++ generic units 187 7.3.3 Implementation of JAVA generic units 188 Summary 188 Further reading 189 Exercises 189 8 Type systems 191 8.1 Inclusion polymorphism 191 8.1.1 Types and subtypes 191 8.1.2 Classes and subclasses 195 8.2 Parametric polymorphism 198 8.2.1 Polymorphic procedures 198 8.2.2 Parameterized types 200 8.2.3 Type inference 202 8.3 Overloading 204 8.4 Type conversions 207 8.5 Implementation notes 208 8.5.1 Implementation of parametric polymorphism 208 Summary 210 Further reading 210 Exercises 211 9 Control flow 215 9.1 Sequencers 215 9.2 Jumps 216 9.3 Escapes 218

- 12. Contents xi 9.4 Exceptions 221 9.5 Implementation notes 226 9.5.1 Implementation of jumps and escapes 226 9.5.2 Implementation of exceptions 227 Summary 227 Further reading 228 Exercises 228 10 Concurrency 231 10.1 Why concurrency? 231 10.2 Programs and processes 233 10.3 Problems with concurrency 234 10.3.1 Nondeterminism 234 10.3.2 Speed dependence 234 10.3.3 Deadlock 236 10.3.4 Starvation 237 10.4 Process interactions 238 10.4.1 Independent processes 238 10.4.2 Competing processes 238 10.4.3 Communicating processes 239 10.5 Concurrency primitives 240 10.5.1 Process creation and control 241 10.5.2 Interrupts 243 10.5.3 Spin locks and wait-free algorithms 243 10.5.4 Events 248 10.5.5 Semaphores 249 10.5.6 Messages 251 10.5.7 Remote procedure calls 252 10.6 Concurrent control abstractions 253 10.6.1 Conditional critical regions 253 10.6.2 Monitors 255 10.6.3 Rendezvous 256 Summary 258 Further reading 258 Exercises 259 Part IV: Paradigms 263 11 Imperative programming 265 11.1 Key concepts 265 11.2 Pragmatics 266 11.2.1 A simple spellchecker 268 11.3 Case study: C 269 11.3.1 Values and types 269 11.3.2 Variables, storage, and control 272

- 13. xii Contents 11.3.3 Bindings and scope 274 11.3.4 Procedural abstraction 274 11.3.5 Independent compilation 275 11.3.6 Preprocessor directives 276 11.3.7 Function library 277 11.3.8 A simple spellchecker 278 11.4 Case study: ADA 281 11.4.1 Values and types 281 11.4.2 Variables, storage, and control 282 11.4.3 Bindings and scope 282 11.4.4 Procedural abstraction 283 11.4.5 Data abstraction 283 11.4.6 Generic abstraction 285 11.4.7 Separate compilation 288 11.4.8 Package library 289 11.4.9 A simple spellchecker 289 Summary 292 Further reading 293 Exercises 293 12 Object-oriented programming 297 12.1 Key concepts 297 12.2 Pragmatics 298 12.3 Case study: C++ 299 12.3.1 Values and types 300 12.3.2 Variables, storage, and control 300 12.3.3 Bindings and scope 300 12.3.4 Procedural abstraction 301 12.3.5 Data abstraction 302 12.3.6 Generic abstraction 306 12.3.7 Independent compilation and preprocessor directives 307 12.3.8 Class and template library 307 12.3.9 A simple spellchecker 308 12.4 Case study: JAVA 311 12.4.1 Values and types 312 12.4.2 Variables, storage, and control 313 12.4.3 Bindings and scope 314 12.4.4 Procedural abstraction 314 12.4.5 Data abstraction 315 12.4.6 Generic abstraction 317 12.4.7 Separate compilation and dynamic linking 318 12.4.8 Class library 319 12.4.9 A simple spellchecker 320 12.5 Case study: ADA95 322 12.5.1 Types 322 12.5.2 Data abstraction 325

- 14. Contents xiii Summary 328 Further reading 328 Exercises 329 13 Concurrent programming 333 13.1 Key concepts 333 13.2 Pragmatics 334 13.3 Case study: ADA95 336 13.3.1 Process creation and termination 336 13.3.2 Mutual exclusion 338 13.3.3 Admission control 339 13.3.4 Scheduling away deadlock 347 13.4 Case study: JAVA 355 13.4.1 Process creation and termination 356 13.4.2 Mutual exclusion 358 13.4.3 Admission control 359 13.5 Implementation notes 361 Summary 363 Further reading 363 Exercises 363 14 Functional programming 367 14.1 Key concepts 367 14.1.1 Eager vs normal-order vs lazy evaluation 368 14.2 Pragmatics 370 14.3 Case study: HASKELL 370 14.3.1 Values and types 370 14.3.2 Bindings and scope 374 14.3.3 Procedural abstraction 376 14.3.4 Lazy evaluation 379 14.3.5 Data abstraction 381 14.3.6 Generic abstraction 382 14.3.7 Modeling state 384 14.3.8 A simple spellchecker 386 Summary 387 Further reading 388 Exercises 389 15 Logic programming 393 15.1 Key concepts 393 15.2 Pragmatics 396 15.3 Case study: PROLOG 396 15.3.1 Values, variables, and terms 396 15.3.2 Assertions and clauses 398 15.3.3 Relations 398 15.3.4 The closed-world assumption 402 15.3.5 Bindings and scope 403

- 15. xiv Contents 15.3.6 Control 404 15.3.7 Input/output 406 15.3.8 A simple spellchecker 407 Summary 409 Further reading 410 Exercises 410 16 Scripting 413 16.1 Pragmatics 413 16.2 Key concepts 414 16.2.1 Regular expressions 415 16.3 Case study: PYTHON 417 16.3.1 Values and types 418 16.3.2 Variables, storage, and control 419 16.3.3 Bindings and scope 421 16.3.4 Procedural abstraction 421 16.3.5 Data abstraction 422 16.3.6 Separate compilation 424 16.3.7 Module library 425 Summary 427 Further reading 427 Exercises 427 Part V: Conclusion 429 17 Language selection 431 17.1 Criteria 431 17.2 Evaluation 433 Summary 436 Exercises 436 18 Language design 437 18.1 Selection of concepts 437 18.2 Regularity 438 18.3 Simplicity 438 18.4 Efficiency 441 18.5 Syntax 442 18.6 Language life cycles 444 18.7 The future 445 Summary 446 Further reading 446 Exercises 447 Bibliography 449 Glossary 453 Index 465

- 16. Preface The first programming language I ever learned was ALGOL60. This language was notable for its elegance and its regularity; for all its imperfections, it stood head and shoulders above its contemporaries. My interest in languages was awakened, and I began to perceive the benefits of simplicity and consistency in language design. Since then I have learned and programmed in about a dozen other languages, and I have struck a nodding acquaintance with many more. Like many pro- grammers, I have found that certain languages make programming distasteful, a drudgery; others make programming enjoyable, even esthetically pleasing. A good language, like a good mathematical notation, helps us to formulate and communi- cate ideas clearly. My personal favorites have been PASCAL, ADA, ML, and JAVA. Each of these languages has sharpened my understanding of what programming is (or should be) all about. PASCAL taught me structured programming and data types. ADA taught me data abstraction, exception handling, and large-scale pro- gramming. ML taught me functional programming and parametric polymorphism. JAVA taught me object-oriented programming and inclusion polymorphism. I had previously met all of these concepts, and understood them in principle, but I did not truly understand them until I had the opportunity to program in languages that exposed them clearly. Contents This book consists of five parts. Chapter 1 introduces the book with an overview of programming linguistics (the study of programming languages) and a brief history of programming and scripting languages. Chapters 2–5 explain the basic concepts that underlie almost all programming languages: values and types, variables and storage, bindings and scope, procedures and parameters. The emphasis in these chapters is on identifying the basic concepts and studying them individually. These basic concepts are found in almost all languages. Chapters 6–10 continue this theme by examining some more advanced con- cepts: data abstraction (packages, abstract types, and classes), generic abstraction (or templates), type systems (inclusion polymorphism, parametric polymor- phism, overloading, and type conversions), sequencers (including exceptions), and concurrency (primitives, conditional critical regions, monitors, and rendezvous). These more advanced concepts are found in the more modern languages. Chapters 11–16 survey the most important programming paradigms, compar- ing and contrasting the long-established paradigm of imperative programming with the increasingly important paradigms of object-oriented and concurrent pro- gramming, the more specialized paradigms of functional and logic programming, and the paradigm of scripting. These different paradigms are based on different xv

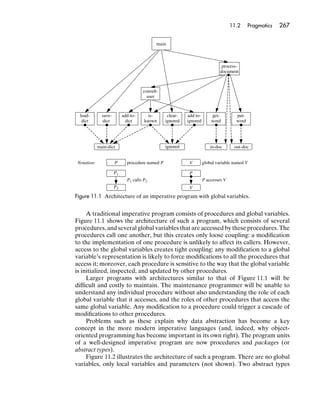

- 17. xvi Preface selections of key concepts, and give rise to sharply contrasting styles of language and of programming. Each chapter identifies the key concepts of the subject paradigm, and presents an overview of one or more major languages, showing how concepts were selected and combined when the language was designed. Several designs and implementations of a simple spellchecker are presented to illustrate the pragmatics of programming in all of the major languages. Chapters 17 and 18 conclude the book by looking at two issues: how to select a suitable language for a software development project, and how to design a new language. The book need not be read sequentially. Chapters 1–5 should certainly be read first, but the remaining chapters could be read in many different orders. Chapters 11–15 are largely self-contained; my recommendation is to read at least some of them after Chapters 1–5, in order to gain some insight into how major languages have been designed. Figure P.1 summarizes the dependencies between the chapters. Examples and case studies The concepts studied in Chapters 2–10 are freely illustrated by examples. These examples are drawn primarily from C, C++, JAVA, and ADA. I have chosen these languages because they are well known, they contrast well, and even their flaws are instructive! 1 Introduction 2 3 4 5 Values and Variables and Bindings and Procedural Types Storage Scope Abstraction 6 7 8 9 10 Data Generic Type Control Concurrency Abstraction Abstraction Systems Flow 11 12 13 14 15 16 Imperative OO Concurrent Functional Logic Scripting Programming Programming Programming Programming Programming 17 18 Language Language Selection Design Figure P.1 Dependencies between chapters of this book.

- 18. Preface xvii The paradigms studied in Chapters 11–16 are illustrated by case studies of major languages: ADA, C, C++, HASKELL, JAVA, PROLOG, and PYTHON. These languages are studied only impressionistically. It would certainly be valuable for readers to learn to program in all of these languages, in order to gain deeper insight, but this book makes no attempt to teach programming per se. The bibliography contains suggested reading on all of these languages. Exercises Each chapter is followed by a number of relevant exercises. These vary from short exercises, through longer ones (marked *), up to truly demanding ones (marked **) that could be treated as projects. A typical exercise is to analyze some aspect of a favorite language, in the same way that various languages are analyzed in the text. Exercises like this are designed to deepen readers’ understanding of languages that they already know, and to reinforce understanding of particular concepts by studying how they are supported by different languages. A typical project is to design some extension or modification to an existing language. I should emphasize that language design should not be undertaken lightly! These projects are aimed particularly at the most ambitious readers, but all readers would benefit by at least thinking about the issues raised. Readership All programmers, not just language specialists, need a thorough understanding of language concepts. This is because programming languages are our most fundamental tools. They influence the very way we think about software design and implementation, about algorithms and data structures. This book is aimed at junior, senior, and graduate students of computer science and information technology, all of whom need some understanding of the fundamentals of programming languages. The book should also be of inter- est to professional software engineers, especially project leaders responsible for language evaluation and selection, designers and implementers of language processors, and designers of new languages and of extensions to existing languages. To derive maximum benefit from this book, the reader should be able to program in at least two contrasting high-level languages. Language concepts can best be understood by comparing how they are supported by different languages. A reader who knows only a language like C, C++, or JAVA should learn a contrasting language such as ADA (or vice versa) at the same time as studying this book. The reader will also need to be comfortable with some elementary concepts from discrete mathematics – sets, functions, relations, and predicate logic – as these are used to explain a variety of language concepts. The relevant mathematical concepts are briefly reviewed in Chapters 2 and 15, in order to keep this book reasonably self-contained. This book attempts to cover all the most important aspects of a large subject. Where necessary, depth has been sacrificed for breadth. Thus the really serious

- 19. xviii Preface student will need to follow up with more advanced studies. The book has an extensive bibliography, and each chapter closes with suggestions for further reading on the topics covered by the chapter. Acknowledgments Bob Tennent’s classic book Programming Language Principles has profoundly influenced the way I have organized this book. Many books on programming languages have tended to be syntax-oriented, examining several popular languages feature by feature, without offering much insight into the underlying concepts or how future languages might be designed. Some books are implementation- oriented, attempting to explain concepts by showing how they are implemented on computers. By contrast, Tennent’s book is semantics-oriented, first identifying and explaining powerful and general semantic concepts, and only then analyzing particular languages in terms of these concepts. In this book I have adopted Ten- nent’s semantics-oriented approach, but placing far more emphasis on concepts that have become more prominent in the intervening two decades. I have also been strongly influenced, in many different ways, by the work of Malcolm Atkinson, Peter Buneman, Luca Cardelli, Frank DeRemer, Edsger Dijkstra, Tony Hoare, Jean Ichbiah, John Hughes, Mehdi Jazayeri, Bill Joy, Robin Milner, Peter Mosses, Simon Peyton Jones, Phil Wadler, and Niklaus Wirth. I wish to thank Bill Findlay for the two chapters (Chapters 10 and 13) he has contributed to this book. His expertise on concurrent programming has made this book broader in scope than I could have made it myself. His numerous suggestions for my own chapters have been challenging and insightful. Last but not least, I would like to thank the Wiley reviewers for their constructive criticisms, and to acknowledge the assistance of the Wiley editorial staff led by Gaynor Redvers-Mutton. David A. Watt Brisbane March 2004

- 20. PART I INTRODUCTION Part I introduces the book with an overview of programming linguistics and a brief history of programming and scripting languages. 1

- 22. Chapter 1 Programming languages In this chapter we shall: • outline the discipline of programming linguistics, which is the study of program- ming languages, encompassing concepts and paradigms, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics, and language processors such as compilers and interpreters; • briefly survey the historical development of programming languages, covering the major programming languages and paradigms. 1.1 Programming linguistics The first high-level programming languages were designed during the 1950s. Ever since then, programming languages have been a fascinating and productive area of study. Programmers endlessly debate the relative merits of their favorite pro- gramming languages, sometimes with almost religious zeal. On a more academic level, computer scientists search for ways to design programming languages that combine expressive power with simplicity and efficiency. We sometimes use the term programming linguistics to mean the study of programming languages. This is by analogy with the older discipline of linguistics, which is the study of natural languages. Both programming languages and natural languages have syntax (form) and semantics (meaning). However, we cannot take the analogy too far. Natural languages are far broader, more expressive, and subtler than programming languages. A natural language is just what a human population speaks and writes, so linguists are restricted to analyzing existing (and dead) natural languages. On the other hand, programming linguists can not only analyze existing programming languages; they can also design and specify new programming languages, and they can implement these languages on computers. Programming linguistics therefore has several aspects, which we discuss briefly in the following subsections. 1.1.1 Concepts and paradigms Every programming language is an artifact, and as such has been consciously designed. Some programming languages have been designed by a single person (such as C++), others by small groups (such as C and JAVA), and still others by large groups (such as ADA). A programming language, to be worthy of the name, must satisfy certain fundamental requirements. 3

- 23. 4 Chapter 1 Programming languages A programming language must be universal. That is to say, every problem must have a solution that can be programmed in the language, if that problem can be solved at all by a computer. This might seem to be a very strong requirement, but even a very small programming language can meet it. Any language in which we can define recursive functions is universal. On the other hand, a language with neither recursion nor iteration cannot be universal. Certain application languages are not universal, but we do not generally classify them as programming languages. A programming language should also be reasonably natural for solving prob- lems, at least problems within its intended application area. For example, a programming language whose only data types are numbers and arrays might be natural for solving numerical problems, but would be less natural for solving prob- lems in commerce or artificial intelligence. Conversely, a programming language whose only data types are strings and lists would be an unnatural choice for solving numerical problems. A programming language must also be implementable on a computer. That is to say, it must be possible to execute every well-formed program in the language. Mathematical notation (in its full generality) is not implementable, because in this notation it is possible to formulate problems that cannot be solved by any computer. Natural languages also are not implementable, because they are impre- cise and ambiguous. Therefore, mathematical notation and natural languages, for entirely different reasons, cannot be classified as programming languages. In practice, a programming language should be capable of an acceptably efficient implementation. There is plenty of room for debate over what is acceptably efficient, especially as the efficiency of a programming language implementation is strongly influenced by the computer architecture. FORTRAN, C, and PASCAL programmers might expect their programs to be almost as efficient (within a factor of 2–4) as the corresponding assembly-language programs. PROLOG programmers have to accept an order of magnitude lower efficiency, but would justify this on the grounds that the language is far more natural within its own application area; besides, they hope that new computer architectures will eventually appear that are more suited for executing PROLOG programs than conventional architectures. In Parts II and III of this book we shall study the concepts that underlie the design of programming languages: data and types, variables and storage, bindings and scope, procedural abstraction, data abstraction, generic abstraction, type systems, control, and concurrency. Although few of us will ever design a programming language (which is extremely difficult to do well), as programmers we can all benefit by studying these concepts. Programming languages are our most basic tools, and we must thoroughly master them to use them effectively. Whenever we have to learn a new programming language and discover how it can be effectively exploited to construct reliable and maintainable programs, and whenever we have to decide which programming language is most suitable for solving a given problem, we find that a good understanding of programming language concepts is indispensable. We can master a new programming language most effectively if we understand the underlying concepts that it shares with other programming languages.

- 24. 1.1 Programming linguistics 5 Just as important as the individual concepts are the ways in which they may be put together to design complete programming languages. Different selections of key concepts support radically different styles of programming, which are called paradigms. There are six major paradigms. Imperative programming is characterized by the use of variables, commands, and procedures; object-oriented programming by the use of objects, classes, and inheritance; concurrent pro- gramming by the use of concurrent processes, and various control abstractions; functional programming by the use of functions; logic programming by the use of relations; and scripting languages by the presence of very high-level features. We shall study all of these paradigms in Part IV of this book. 1.1.2 Syntax, semantics, and pragmatics Every programming language has syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. We have seen that natural languages also have syntax and semantics, but pragmatics is unique to programming languages. • A programming language’s syntax is concerned with the form of programs: how expressions, commands, declarations, and other constructs must be arranged to make a well-formed program. • A programming language’s semantics is concerned with the meaning of programs: how a well-formed program may be expected to behave when executed on a computer. • A programming language’s pragmatics is concerned with the way in which the language is intended to be used in practice. Syntax influences how programs are written by the programmer, read by other programmers, and parsed by the computer. Semantics determines how programs are composed by the programmer, understood by other programmers, and interpreted by the computer. Pragmatics influences how programmers are expected to design and implement programs in practice. Syntax is important, but semantics and pragmatics are more important still. To underline this point, consider how an expert programmer thinks, given a programming problem to solve. Firstly, the programmer decomposes the prob- lem, identifying suitable program units (procedures, packages, abstract types, or classes). Secondly, the programmer conceives a suitable implementation of each program unit, deploying language concepts such as types, control structures, exceptions, and so on. Lastly, the programmer codes each program unit. Only at this last stage does the programming language’s syntax become relevant. In this book we shall pay most attention to semantic and pragmatic issues. A given construct might be provided in several programming languages, with varia- tions in syntax that are essentially superficial. Semantic issues are more important. We need to appreciate subtle differences in meaning between apparently similar constructs. We need to see whether a given programming language confuses dis- tinct concepts, or supports an important concept inadequately, or fails to support it at all. In this book we study those concepts that are so important that they are supported by a variety of programming languages.

- 25. 6 Chapter 1 Programming languages In order to avoid distracting syntactic variations, wherever possible we shall illustrate each concept using the following programming languages: C, C++, JAVA, and ADA. C is now middle-aged, and its design defects are numerous; however, it is very widely known and used, and even its defects are instructive. C++ and JAVA are modern and popular object-oriented languages. ADA is a programming language that supports imperative, object-oriented, and concurrent programming. None of these programming languages is by any means perfect. The ideal programming language has not yet been designed, and is never likely to be! 1.1.3 Language processors This book is concerned only with high-level languages, i.e., programming languages that are (more or less) independent of the machines on which programs are executed. High-level languages are implemented by compiling programs into machine language, by interpreting them directly, or by some combination of compilation and interpretation. Any system for processing programs – executing programs, or preparing them for execution – is called a language processor. Language processors include com- pilers, interpreters, and auxiliary tools like source-code editors and debuggers. We have seen that a programming language must be implementable. However, this does not mean that programmers need to know in detail how a programming language is implemented in order to understand it thoroughly. Accordingly, implementation issues will receive limited attention in this book, except for a short section (‘‘Implementation notes’’) at the end of each chapter. 1.2 Historical development Today’s programming languages are the product of developments that started in the 1950s. Numerous concepts have been invented, tested, and improved by being incorporated in successive programming languages. With very few exceptions, the design of each programming language has been strongly influenced by experience with earlier languages. The following brief historical survey summarizes the ancestry of the major programming languages and sketches the development of the concepts introduced in this book. It also reminds us that today’s programming languages are not the end product of developments in programming language design; exciting new concepts, languages, and paradigms are still being developed, and the programming language scene ten years from now will probably be rather different from today’s. Figure 1.1 summarizes the dates and ancestry of several important program- ming languages. This is not the place for a comprehensive survey, so only the major programming languages are mentioned. FORTRAN was the earliest major high-level language. It introduced symbolic expressions and arrays, and also procedures (‘‘subroutines’’) with parameters. In other respects FORTRAN (in its original form) was fairly low-level; for example, con- trol flow was largely effected by conditional and unconditional jumps. FORTRAN has developed a long way from its original design; the latest version was standardized as recently as 1997.

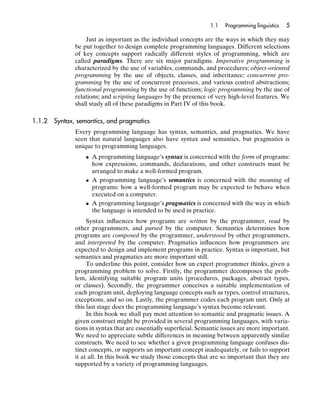

- 26. 1.2 Historical development 7 object-oriented imperative concurrent functional logic languages languages languages languages languages 1950 FORTRAN LISP ALGOL60 COBOL 1960 PL/I SIMULA ALGOL68 PASCAL 1970 SMALLTALK PROLOG C MODULA ML 1980 ADA83 C++ HASKELL 1990 JAVA ADA95 Key: C# major minor 2000 influence influence Figure 1.1 Dates and ancestry of major programming languages. COBOL was another early major high-level language. Its most important contribution was the concept of data descriptions, a forerunner of today’s data types. Like FORTRAN, COBOL’s control flow was fairly low-level. Also like FORTRAN, COBOL has developed a long way from its original design, the latest version being standardized in 2002. ALGOL60 was the first major programming language to be designed for communicating algorithms, not just for programming a computer. ALGOL60 intro- duced the concept of block structure, whereby variables and procedures could be declared wherever in the program they were needed. It was also the first major programming language to support recursive procedures. ALGOL60 influ- enced numerous successor languages so strongly that they are collectively called ALGOL-like languages. FORTRAN and ALGOL60 were most useful for numerical computation, and COBOL for commercial data processing. PL/I was an attempt to design a general-purpose programming language by merging features from all three. On

- 27. 8 Chapter 1 Programming languages top of these it introduced many new features, including low-level forms of excep- tions and concurrency. The resulting language was huge, complex, incoherent, and difficult to implement. The PL/I experience showed that simply piling feature upon feature is a bad way to make a programming language more powerful and general-purpose. A better way to gain expressive power is to choose an adequate set of concepts and allow them to be combined systematically. This was the design philosophy of ALGOL68. For instance, starting with concepts such as integers, arrays, and procedures, the ALGOL68 programmer can declare an array of integers, an array of arrays, or an array of procedures; likewise, the programmer can define a procedure whose parameter or result is an integer, an array, or another procedure. PASCAL, however, turned out to be the most popular of the ALGOL-like languages. It is simple, systematic, and efficiently implementable. PASCAL and ALGOL68 were among the first major programming languages with both a rich variety of control structures (conditional and iterative commands) and a rich variety of data types (such as arrays, records, and recursive types). C was originally designed to be the system programming language of the UNIX operating system. The symbiotic relationship between C and UNIX has proved very good for both of them. C is suitable for writing both low-level code (such as the UNIX system kernel) and higher-level applications. However, its low-level features are easily misused, resulting in code that is unportable and unmaintainable. PASCAL’s powerful successor, ADA, introduced packages and generic units – designed to aid the construction of large modular programs – as well as high-level forms of exceptions and concurrency. Like PL/I, ADA was intended by its designers to become the standard general-purpose programming language. Such a stated ambition is perhaps very rash, and ADA also attracted a lot of criticism. (For example, Tony Hoare quipped that PASCAL, like ALGOL60 before it, was a marked advance on its successors!) The critics were wrong: ADA was very well designed, is particularly suitable for developing high-quality (reliable, robust, maintainable, efficient) software, and is the language of choice for mission-critical applications in fields such as aerospace. We can discern certain trends in the history of programming languages. One has been a trend towards higher levels of abstraction. The mnemonics and symbolic labels of assembly languages abstract away from operation codes and machine addresses. Variables and assignment abstract away from inspection and updating of storage locations. Data types abstract away from storage structures. Control structures abstract away from jumps. Procedures abstract away from subroutines. Packages achieve encapsulation, and thus improve modularity. Generic units abstract procedures and packages away from the types of data on which they operate, and thus improve reusability. Another trend has been a proliferation of paradigms. Nearly all the languages mentioned so far have supported imperative programming, which is characterized by the use of commands and procedures that update variables. PL/I and ADA sup- port concurrent programming, characterized by the use of concurrent processes. However, other paradigms have also become popular and important.

- 28. 1.2 Historical development 9 Object-oriented programming is based on classes of objects. An object has variable components and is equipped with certain operations. Only these opera- tions can access the object’s variable components. A class is a family of objects with similar variable components and operations. Classes turn out to be convenient reusable program units, and all the major object-oriented languages are equipped with rich class libraries. The concepts of object and class had their origins in SIMULA, yet another ALGOL-like language. SMALLTALK was the earliest pure object-oriented language, in which entire programs are constructed from classes. C++ was designed by adding object-oriented concepts to C. C++ brought together the C and object-oriented programming communities, and thus became very popular. Nevertheless, its design is clumsy; it inherited all C’s shortcomings, and it added some more of its own. JAVA was designed by drastically simplifying C++, removing nearly all its shortcomings. Although primarily a simple object-oriented language, JAVA can also be used for distributed and concurrent programming. JAVA is well suited for writing applets (small portable application programs embedded in Web pages), as a consequence of a highly portable implementation (the Java Virtual Machine) that has been incorporated into all the major Web browsers. Thus JAVA has enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with the Web, and both have experienced enormous growth in popularity. C# is very similar to JAVA, apart from some relatively minor design improvements, but its more efficient implementation makes it more suitable for ordinary application programming. Functional programming is based on functions over types such as lists and trees. The ancestral functional language was LISP, which demonstrated at a remarkably early date that significant programs can be written without resorting to variables and assignment. ML and HASKELL are modern functional languages. They treat functions as ordinary values, which can be passed as parameters and returned as results from other functions. Moreover, they incorporate advanced type systems, allowing us to write polymorphic functions (functions that operate on data of a variety of types). ML (like LISP) is an impure functional language, since it does support variables and assignment. HASKELL is a pure functional language. As noted in Section 1.1.1, mathematical notation in its full generality is not implementable. Nevertheless, many programming language designers have sought to exploit subsets of mathematical notation in programming languages. Logic programming is based on a subset of predicate logic. Logic programs infer relationships between values, as opposed to computing output values from input values. PROLOG was the ancestral logic language, and is still the most popular. In its pure logical form, however, PROLOG is rather weak and inefficient, so it has been extended with extra-logical features to make it more usable as a programming language. Programming languages are intended for writing application programs and systems programs. However, there are other niches in the ecology of computing. An operating system such as UNIX provides a language in which a user or system administrator can issue commands from the keyboard, or store a command

- 29. 10 Chapter 1 Programming languages script that will later be called whenever required. An office system (such as a word processor or spreadsheet system) might enable the user to store a script (‘‘macro’’) embodying a common sequence of commands, typically written in VISUAL BASIC. The Internet has created a variety of new niches for scripting. For example, the results of a database query might be converted to a dynamic Web page by a script, typically written in PERL. All these applications are examples of scripting. Scripts (‘‘programs’’ written in scripting languages) typically are short and high-level, are developed very quickly, and are used to glue together subsystems written in other languages. So scripting languages, while having much in common with imperative programming languages, have different design constraints. The most modern and best-designed of these scripting languages is PYTHON. Summary In this introductory chapter: • We have seen what is meant by programming linguistics, and the topics encompassed by this term: concepts and paradigms; syntax, semantics, and pragmatics; and language processors. • We have briefly surveyed the history of programming languages. We saw how new languages inherited successful concepts from their ancestors, and sometimes intro- duced new concepts of their own. We also saw how the major paradigms evolved: imperative programming, object-oriented programming, concurrent programming, functional programming, logic programming, and scripting. Further reading Programming language concepts and paradigms are cov- in WEXELBLAT (1980). Comparative studies of program- ered not only in this book, but also in TENNENT (1981), ming languages may be found in HOROWITZ (1995), PRATT GHEZZI and JAZAYERI (1997), SEBESTA (2001), and SETHI and ZELCOWITZ (2001), and SEBESTA (2001). A survey (1996). Programming language syntax and semantics are of scripting languages may be found in BARRON covered in WATT (1991). Programming language proces- (2000). sors are covered in AHO et al. (1986), APPEL (1998), and WATT and BROWN (2000). More detailed information on the programming languages The early history of programming languages (up to the mentioned in this chapter may be found in the references 1970s) was the theme of a major conference, reported cited in Table 1.1. Exercises Note: Harder exercises are marked *. Exercises for Section 1.1 1.1.1 Here is a whimsical exercise to get you started. For each programming language that you know, write down the shortest program that does nothing at all. How long is this program? This is quite a good measure of the programming language’s verbosity!

- 30. Exercises 11 Table 1.1 Descriptions of major programming and scripting languages. Programming language Description ADA ISO/IEC (1995); www.ada-auth.org/∼acats/arm.html ALGOL60 Naur (1963) ALGOL68 van Wijngaarden et al. (1976) C Kernighan and Ritchie (1989); ISO/IEC (1999) C++ Stroustrup (1997); ISO/IEC (1998) C# Drayton et al. (2002) COBOL ISO/IEC (2002) FORTRAN ISO/IEC (1997) JAVA Joy et al. (2000); Flanagan (2002) LISP McCarthy et al. (1965); ANSI (1994) HASKELL Thompson (1999) ML Milner et al. (1997) MODULA Wirth (1977) PASCAL ISO (1990) PERL Wall et al. (2000) PL/I ISO (1979) PROLOG Bratko (1990) PYTHON Beazley (2001); www.python.org/doc/current/ref/ SIMULA Birtwhistle et al. (1979) SMALLTALK Goldberg and Robson (1989) Exercises for Section 1.2 *1.2.1 The brief historical survey of Section 1.2 does not mention all major pro- gramming languages (only those that have been particularly influential, in the author’s opinion). If a favorite language of yours has been omitted, explain why you think that it is important enough to be included, and show where your language fits into Figure 1.1. *1.2.2 FORTRAN and COBOL are very old programming languages, but still widely used today. How would you explain this paradox? *1.2.3 Imperative programming was the dominant paradigm from the dawn of com- puting until about 1990, after which if was overtaken by object-oriented programming. How would you explain this development? Why has functional or logic programming never become dominant?

- 32. PART II BASIC CONCEPTS Part II explains the more elementary programming language concepts, which are supported by almost all programming languages: • values and types • variables and storage • bindings and scope • procedural abstraction (procedures and parameters). 13

- 34. Chapter 2 Values and types Data are the raw material of computation, and are just as important (and valuable) as the programs that manipulate the data. In computer science, therefore, the study of data is considered as an important topic in its own right. In this chapter we shall study: • types of values that may be used as data in programming languages; • primitive, composite, and recursive types; • type systems, which group values into types and constrain the operations that may be performed on these values; • expressions, which are program constructs that compute new values; • how values of primitive, composite, and recursive types are represented. (In Chapter 3 we shall go on to study how values may be stored, and in Chapter 4 how values may be bound to identifiers.) 2.1 Types A value is any entity that can be manipulated by a program. Values can be evaluated, stored, passed as arguments, returned as function results, and so on. Different programming languages support different types of values: • C supports integers, real numbers, structures, arrays, unions, pointers to variables, and pointers to functions. (Integers, real numbers, and pointers are primitive values; structures, arrays, and unions are composite values.) • C++, which is a superset of C, supports all the above types of values plus objects. (Objects are composite values.) • JAVA supports booleans, integers, real numbers, arrays, and objects. (Booleans, integers, and real numbers are primitive values; arrays and objects are composite values.) • ADA supports booleans, characters, enumerands, integers, real numbers, records, arrays, discriminated records, objects (tagged records), strings, pointers to data, and pointers to procedures. (Booleans, characters, enu- merands, integers, real numbers, and pointers are primitive values; records, arrays, discriminated records, objects, and strings are composite values.) Most programming languages group values into types. For instance, nearly all languages make a clear distinction between integer and real numbers. Most 15

- 35. 16 Chapter 2 Values and types languages also make a clear distinction between booleans and integers: integers can be added and multiplied, while booleans can be subjected to operations like not, and, and or. What exactly is a type? The most obvious answer, perhaps, is that a type is a set of values. When we say that v is a value of type T, we mean simply that v ∈ T. When we say that an expression E is of type T, we are asserting that the result of evaluating E will be a value of type T. However, not every set of values is suitable to be regarded as a type. We insist that each operation associated with the type behaves uniformly when applied to all values of the type. Thus {false, true} is a type because the operations not, and, and or operate uniformly over the values false and true. Also, {. . . , −2, −1, 0, +1, +2, . . .} is a type because operations such as addition and multiplication operate uniformly over all these values. But {13, true, Monday} is not a type, since there are no useful operations over this set of values. Thus we see that a type is characterized not only by its set of values, but also by the operations over that set of values. Therefore we define a type to be a set of values, equipped with one or more operations that can be applied uniformly to all these values. Every programming language supports both primitive types, whose values are primitive, and composite types, whose values are composed from simpler values. Some languages also have recursive types, a recursive type being one whose values are composed from other values of the same type. We examine primitive, composite, and recursive types in the next three sections. 2.2 Primitive types A primitive value is one that cannot be decomposed into simpler values. A primitive type is one whose values are primitive. Every programming language provides built-in primitive types. Some lan- guages also allow programs to define new primitive types. 2.2.1 Built-in primitive types One or more primitive types are built-in to every programming language. The choice of built-in primitive types tells us much about the programming language’s intended application area. Languages intended for commercial data processing (such as COBOL) are likely to have primitive types whose values are fixed-length strings and fixed-point numbers. Languages intended for numerical computation (such as FORTRAN) are likely to have primitive types whose values are real numbers (with a choice of precisions) and perhaps also complex numbers. A language intended for string processing (such as SNOBOL) is likely to have a primitive type whose values are strings of arbitrary length. Nevertheless, certain primitive types crop up in a variety of languages, often under different names. For example, JAVA has boolean, char, int, and float, whereas ADA has Boolean, Character, Integer, and Float. These name differences are of no significance. For the sake of consistency, we shall use Boolean,

- 36. 2.2 Primitive types 17 Character, Integer, and Float as names for the most common primitive types: Boolean = {false, true} (2.1) Character = {. . . , ‘a’, . . . , ‘z’, . . . , ‘0’, . . . , ‘9’, . . . , ‘?’, . . .} (2.2) Integer = {. . . , −2, −1, 0, +1, +2, . . .} (2.3) Float = {. . . , −1.0, . . . , 0.0, . . . , +1.0, . . .} (2.4) (Here we are focusing on the set of values of each type.) The Boolean type has exactly two values, false and true. In some languages these two values are denoted by the literals false and true, in others by predefined identifiers false and true. The Character type is a language-defined or implementation-defined set of characters. The chosen character set is usually ASCII (128 characters), ISO LATIN (256 characters), or UNICODE (65 536 characters). The Integer type is a language-defined or implementation-defined range of whole numbers. The range is influenced by the computer’s word size and integer arithmetic. For instance, on a 32-bit computer with two’s complement arithmetic, Integer will be {−2 147 483 648, . . . , +2 147 483 647}. The Float type is a language-defined or implementation-defined subset of the (rational) real numbers. The range and precision are determined by the computer’s word size and floating-point arithmetic. The Character, Integer, and Float types are usually implementation-defined, i.e., the set of values is chosen by the compiler. Sometimes, however, these types are language-defined, i.e., the set of values is defined by the programming language. In particular, JAVA defines all its types precisely. The cardinality of a type T, written #T, is the number of distinct values in T. For example: #Boolean = 2 (2.5) #Character = 256 (ISO LATIN character set) (2.6a) #Character = 65 536 (UNICODE character set) (2.6b) Although nearly all programming languages support the Boolean, Character, Integer, and Float types in one way or another, there are many complications: • Not all languages have a distinct type corresponding to Boolean. For example, C++ has a type named bool, but its values are just small integers; there is a convention that zero represents false and any other integer represents true. This convention originated in C. • Not all languages have a distinct type corresponding to Character. For example, C, C++, and JAVA all have a type char, but its values are just small integers; no distinction is made between a character and its internal representation. • Some languages provide not one but several integer types. For example, JAVA provides byte {−128, . . . , +127}, short {−32 768, . . . , +32 767}, int {−2 147 483 648, . . . , +2 147 483 647}, and long {−9 223 372 036 854 775 808, . . . , +9 223 372 036 854 775 807}. C and

- 37. 18 Chapter 2 Values and types C++ also provide a variety of integer types, but they are implementation- defined. • Some languages provide not one but several floating-point types. For example, C, C++, and JAVA provide both float and double, of which the latter provides greater range and precision. EXAMPLE 2.1 JAVA and C++ integer types Consider the following JAVA declarations: int countryPop; long worldPop; The variable countryPop could be used to contain the current population of any country (since no country yet has a population exceeding 2 billion). The variable worldPop could be used to contain the world’s total population. But note that the program would fail if worldPop’s type were int rather than long (since the world’s total population now exceeds 6 billion). A C++ program with the same declarations would be unportable: a C++ compiler may choose {−65 536, . . . , +65 535} as the set of int values! If some types are implementation-defined, the behavior of programs may vary from one computer to another, even programs written in high-level languages. This gives rise to portability problems: a program that works well on one computer might fail when moved to a different computer. One way to avoid such portability problems is for the programming language to define all its primitive types precisely. As we have seen, this approach is taken by JAVA. 2.2.2 Defined primitive types Another way to avoid portability problems is to allow programs to define their own integer and floating-point types, stating explicitly the desired range and/or precision for each type. This approach is taken by ADA. EXAMPLE 2.2 ADA integer types Consider the following ADA declarations: type Population is range 0 .. 1e10; countryPop: Population; worldPop: Population; The integer type defined here has the following set of values: Population = {0, . . . , 1010 }

- 38. 2.2 Primitive types 19 and its cardinality is: #Population = 1010 + 1 This code is completely portable – provided only that the computer is capable of supporting the specified range of integers. In ADA we can define a completely new primitive type by enumerating its values (more precisely, by enumerating identifiers that will denote its values). Such a type is called an enumeration type, and its values are called enumerands. C and C++ also support enumerations, but in these languages an enumeration type is actually an integer type, and each enumerand denotes a small integer. EXAMPLE 2.3 ADA and C++ enumeration types The following ADA type definition: type Month is (jan, feb, mar, apr, may, jun, jul, aug, sep, oct, nov, dec); defines a completely new type, whose values are twelve enumerands: Month = {jan, feb, mar, apr, may, jun, jul, aug, sep, oct, nov, dec} The cardinality of this type is: #Month = 12 The enumerands of type Month are distinct from the values of any other type. Note that we must carefully distinguish between these enumerands (which for convenience we have written as jan, feb, etc.) and the identifiers that denote them in the program (jan, feb, etc.). This distinction is necessary because the identifiers might later be redeclared. (For example, we might later redeclare dec as a procedure that decrements an integer; but the enumerand dec still exists and can be computed.) By contrast, the C++ type definition: enum Month {jan, feb, mar, apr, may, jun, jul, aug, sep, oct, nov, dec}; defines Month to be an integer type, and binds jan to 0, feb to 1, and so on. Thus: Month = {0, 1, 2, . . . , 11} 2.2.3 Discrete primitive types A discrete primitive type is a primitive type whose values have a one-to-one relationship with a range of integers. This is an important concept in ADA, in which values of any discrete primitive type may be used for array indexing, counting, and so on. The discrete primitive types in ADA are Boolean, Character, integer types, and enumeration types.

- 39. 20 Chapter 2 Values and types EXAMPLE 2.4 ADA discrete primitive types Consider the following ADA code: freq: array (Character) of Natural; ... for ch in Character loop freq(ch) := 0; end loop; The indices of the array freq are values of type Character. Likewise, the loop control variable ch takes a sequence of values of type Character. Also consider the following ADA code: type Month is (jan, feb, mar, apr, may, jun, jul, aug, sep, oct, nov, dec); length: array (Month) of Natural := (31, 28, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31); ... for mth in Month loop put(length(mth)); end loop; The indices of the array length are values of type Month. Likewise, the loop control variable mth takes a sequence of values of type Month. Most programming languages allow only integers to be used for counting and array indexing. C and C++ allow enumerands also to be used for counting and array indexing, since they classify enumeration types as integer types. 2.3 Composite types A composite value (or data structure) is a value that is composed from simpler values. A composite type is a type whose values are composite. Programming languages support a huge variety of composite values: tuples, structures, records, arrays, algebraic types, discriminated records, objects, unions, strings, lists, trees, sequential files, direct files, relations, etc. The variety might seem bewildering, but in fact nearly all these composite values can be understood in terms of a small number of structuring concepts, which are: • Cartesian products (tuples, records) • mappings (arrays) • disjoint unions (algebraic types, discriminated records, objects) • recursive types (lists, trees). (For sequential files, direct files, and relations see Exercise 2.3.6.) We discuss Cartesian products, mappings, and disjoint unions in this section, and recursive types in Section 2.4. Each programming language provides its own notation for describing composite types. Here we shall use mathematical notation

- 40. 2.3 Composite types 21 that is concise, standard, and suitable for defining sets of values structured as Cartesian products, mappings, and disjoint unions. 2.3.1 Cartesian products, structures, and records In a Cartesian product, values of several (possibly different) types are grouped into tuples. We use the notation (x, y) to stand for the pair whose first component is x and whose second component is y. We use the notation S × T to stand for the set of all pairs (x, y) such that x is chosen from set S and y is chosen from set T. Formally: S × T = {(x, y) | x ∈ S; y ∈ T} (2.7) This is illustrated in Figure 2.1. The basic operations on pairs are: • construction of a pair from two component values; • selection of the first or second component of a pair. We can easily infer the cardinality of a Cartesian product: #(S × T) = #S × #T (2.8) This equation motivates the use of the notation ‘‘×’’ for Cartesian product. We can extend the notion of Cartesian product from pairs to tuples with any number of components. In general, the notation S1 × S2 × . . . × Sn stands for the set of all n-tuples, such that the first component of each n-tuple is chosen from S1 , the second component from S2 , . . . , and the nth component from Sn . The structures of C and C++, and the records of ADA, can be understood in terms of Cartesian products. EXAMPLE 2.5 ADA records Consider the following ADA definitions: type Month is (jan, feb, mar, apr, may, jun, jul, aug, sep, oct, nov, dec); type Day_Number is range 1 .. 31; type Date is record m: Month; d: Day_Number; end record; (u, a) (u, b) (u, c) × = u v a b c (v, a) (v, b) (v, c) S T Figure 2.1 Cartesian product of S×T sets S and T.

- 41. 22 Chapter 2 Values and types This record type has the set of values: Date = Month × Day-Number = {jan, feb, . . . , dec} × {1, . . . , 31} This type’s cardinality is: #Date = #Month × #Day-Number = 12 × 31 = 372 and its values are the following pairs: (jan, 1) (jan, 2) (jan, 3) ... (jan, 31) (feb, 1) (feb, 2) (feb, 3) ... (feb, 31) ... ... ... ... ... (dec, 1) (dec, 2) (dec, 3) ... (dec, 31) Note that the Date type models real-world dates only approximately: some Date values, such as (feb, 31), do not correspond to real-world dates. (This is a common problem in data modeling. Some real-world data are too awkward to model exactly by programming language types, so our data models have to be approximate.) The following code illustrates record construction: someday: Date := (m => jan, d => 1); The following code illustrates record component selection: put(someday.m + 1); put("/"); put(someday.d); someday.d := 29; someday.m := feb; Here someday.m selects the first component, and someday.d the second component, of the record someday. Note that the use of component identifiers m and d in record construction and selection enables us to write code that does not depend on the order of the components. EXAMPLE 2.6 C++ structures Consider the following C++ definitions: enum Month {jan, feb, mar, apr, may, jun, jul, aug, sep, oct, nov, dec}; struct Date { Month m; byte d; }; This structure type has the set of values: Date = Month × Byte = {jan, feb, . . . , dec} × {0, . . . , 255} This type models dates even more crudely than its ADA counterpart in Example 2.5. The following code illustrates structure construction: struct Date someday = {jan, 1}; The following code illustrates structure selection: printf("%d/%d", someday.m + 1, someday.d); someday.d = 29; someday.m = feb;

- 42. 2.3 Composite types 23 A special case of a Cartesian product is one where all tuple components are chosen from the same set. The tuples in this case are said to be homogeneous. For example: S2 = S × S (2.9) means the set of homogeneous pairs whose components are both chosen from set S. More generally we write: Sn = S × . . . × S (2.10) to mean the set of homogeneous n-tuples whose components are all chosen from set S. The cardinality of a set of homogeneous n-tuples is given by: #(Sn ) = (#S)n (2.11) This motivates the superscript notation. Finally, let us consider the special case where n = 0. Equation (2.11) tells us that S0 should have exactly one value. This value is the empty tuple (), which is the unique tuple with no components at all. We shall find it useful to define a type that has the empty tuple as its only value: Unit = {()} (2.12) This type’s cardinality is: #Unit = 1 (2.13) Note that Unit is not the empty set (whose cardinality is 0). Unit corresponds to the type named void in C, C++, and JAVA, and to the type null record in ADA. 2.3.2 Mappings, arrays, and functions The notion of a mapping from one set to another is extremely important in programming languages. This notion in fact underlies two apparently different language features: arrays and functions. We write: m:S→T to state that m is a mapping from set S to set T. In other words, m maps every value in S to a value in T. (Read the symbol ‘‘→’’ as ‘‘maps to’’.) If m maps value x in set S to value y in set T, we write y = m(x). The value y is called the image of x under m. Two different mappings from S = {u, v} to T = {a, b, c} are illustrated in Figure 2.2. We use notation such as {u → a, v → c} to denote the mapping that maps u to a and v to c. The notation S → T stands for the set of all mappings from S to T. Formally: S → T = {m | x ∈ S ⇒ m(x) ∈ T} (2.14) This is illustrated in Figure 2.3. Let us deduce the cardinality of S → T. Each value in S has #T possible images under a mapping in S → T. There are #S such values in S. Therefore there

- 43. 24 Chapter 2 Values and types u v u v S S T T a b c a b c Figure 2.2 Two different mappings in {u → a, v → c} {u → c, v → c} S → T. {u → a, v → a} {u → a, v → b} {u → a, v → c} → = u v a b c {u → b, v → a} {u → b, v → b} {u → b, v → c} S T {u → c, v → a} {u → c, v → b} {u → c, v → c} S→T Figure 2.3 Set of all mappings in S → T. are #T × #T × . . . × #T possible mappings (#S copies of #T multiplied together). In short: #(S → T) = (#T)#S (2.15) An array is an indexed sequence of components. An array has one component of type T for each value in type S, so the array itself has type S → T. The length of the array is its number of components, which is #S. Arrays are found in all imperative and object-oriented languages. The type S must be finite, so an array is a finite mapping. In practice, S is always a range of consecutive values, which is called the array’s index range. The limits of the index range are called its lower bound and upper bound. The basic operations on arrays are: • construction of an array from its components; • indexing, i.e., selecting a particular component of an array, given its index. The index used to select an array component is a computed value. Thus array index- ing differs fundamentally from Cartesian-product selection (where the component to be selected is always explicit). C and C++ restrict an array’s index range to be a range of integers whose lower bound is zero. EXAMPLE 2.7 C++ arrays Consider the C++ declaration: bool p[3];

- 44. 2.3 Composite types 25 The indices of this array range from the lower bound 0 to the upper bound 2. The set of possible values of this array is therefore: {0, 1, 2} → {false, true} The cardinality of this set of values is 23 , and the values are the following eight finite mappings: {0 → false, 1 → false, 2 → false} {0 → true, 1 → false, 2 → false} {0 → false, 1 → false, 2 → true} {0 → true, 1 → false, 2 → true} {0 → false, 1 → true, 2 → false} {0 → true, 1 → true, 2 → false} {0 → false, 1 → true, 2 → true} {0 → true, 1 → true, 2 → true} The following code illustrates array construction: bool p[] = {true, false, true}; The following code illustrates array indexing (using an int variable c): p[c] = !p[c]; JAVA also restricts an array’s index range to be a range of integers whose lower bound is zero. JAVA arrays are similar to C and C++ arrays, but they are in fact objects. ADA allows an array’s index range to be chosen by the programmer, the only restriction being that the index range must be a discrete primitive type. EXAMPLE 2.8 ADA arrays Consider the ADA type definitions: type Color is (red, green, blue); type Pixel is array (Color) of Boolean; The set of values of this array type is: Pixel = Color → Boolean = {red, green, blue} → {false, true} This type’s cardinality is: #Pixel = (#Boolean)#Color = 23 = 8 and its values are the following eight finite mappings: {red → false, green → false, blue → false} {red → true, green → false, blue → false} {red → false, green → false, blue → true} {red → true, green → false, blue → true} {red → false, green → true, blue → false} {red → true, green → true, blue → false} {red → false, green → true, blue → true} {red → true, green → true, blue → true} The following code illustrates array construction: p: Pixel := (red => true, green => false, blue => true);

- 45. 26 Chapter 2 Values and types or more concisely: p: Pixel := (true, false, true); The following code illustrates array indexing (using a Color variable c): p(c) := not p(c); Most programming languages support multidimensional arrays. A component of an n-dimensional array is accessed using n index values. We can think of an n-dimensional array as having a single index that happens to be an n-tuple. EXAMPLE 2.9 ADA two-dimensional arrays Consider the following ADA definitions: type Xrange is range 0 .. 511; type Yrange is range 0 .. 255; type Window is array (YRange, XRange) of Pixel; This two-dimensional array type has the following set of values: Window = Yrange × Xrange → Pixel = {0, . . . , 255} × {0, . . . , 511} → Pixel An array of this type is indexed by a pair of integers. Thus w(8,12) accesses that component of w whose index is the pair (8, 12). Mappings occur in programming languages, not only as arrays, but also as function procedures (more usually called simply functions). We can implement a mapping in S → T by means of a function procedure, which takes a value in S (the argument) and computes its image in T (the result). Here the set S is not necessarily finite. EXAMPLE 2.10 Functions implementing mappings Consider the following C++ function: bool isEven (int n) { return (n % 2 == 0); } This function implements one particular mapping in Integer → Boolean, namely: {. . . , 0 → true, 1 → false, 2 → true, 3 → false, . . .} We could employ a different algorithm: bool isEven (int n) { int m = (n < 0 ? -n : n);

- 46. 2.3 Composite types 27 while (m > 1) m -= 2; return (m == 0); } but the function still implements the same mapping. We can also write other functions that implement different mappings in Integer → Boolean, such as: isOdd {. . . , 0 → false, 1 → true, 2 → false, 3 → true, . . .} isPositive {. . . , −2 → false, −1 → false, 0 → false, 1 → true, 2 → true, . . .} isPrime {. . . , 0 → false, 1 → false, 2 → true, 3 → true, 4 → false, . . .} In most programming languages, a function may have multiple parameters. A function with n parameters will have n arguments passed to it when called. We can view such a function as receiving a single argument that happens to be an n-tuple. EXAMPLE 2.11 Functions with multiple parameters The following C or C++ function: float power (float b, int n) { ... } implements a particular mapping in Float × Integer → Float. Presumably, it maps the pair (1.5, 2) to 2.25, the pair (4.0, −2) to 0.0625, and so on. It is noteworthy that mappings can be implemented by either arrays or functions in programming languages (and that mappings from n-tuples can be implemented by either n-dimensional arrays or n-parameter functions). Indeed, we can sometimes use arrays and functions interchangeably – see Exercise 2.3.5. It is important not to confuse function procedures with mathematical func- tions. A function procedure implements a mapping by means of a particular algorithm, and thus has properties (such as efficiency) that are not shared by mathematical functions. Furthermore, a function procedure that inspects or mod- ifies global variables (for example a function procedure that returns the current time of day, or one that computes and returns a random number) does not corre- spond to any mathematical function. For these reasons, when using the unqualified term function in the context of programming languages, we must be very clear whether we mean a mathematical function (mapping) or a function procedure. 2.3.3 Disjoint unions, discriminated records, and objects Another kind of composite value is the disjoint union, whereby a value is chosen from one of several (usually different) sets.

- 47. 28 Chapter 2 Values and types We use the notation S + T to stand for a set of disjoint-union values, each of which consists of a tag together with a variant chosen from either set S or set T. The tag indicates the set from which the variant was chosen. Formally: S + T = {left x | x ∈ S} ∪ {right y | y ∈ T} (2.16) Here left x stands for a disjoint-union value with tag left and variant x chosen from S, while right x stands for a disjoint-union value with tag right and variant y chosen from T. This is illustrated in Figure 2.4. When we wish to make the tags explicit, we will use the notation left S + right T: left S + right T = {left x | x ∈ S} ∪ {right y | y ∈ T} (2.17) When the tags are irrelevant, we will still use the simpler notation S + T. Note that the tags serve only to distinguish the variants. They must be distinct, but otherwise they may be chosen freely. The basic operations on disjoint-union values in S + T are: • construction of a disjoint-union value, by taking a value in either S or T and tagging it accordingly; • tag test, determining whether the variant was chosen from S or T; • projection to recover the variant in S or the variant in T (as the case may be). For example, a tag test on the value right b determines that the variant was chosen from T, so we can proceed to project it to recover the variant b. We can easily infer the cardinality of a disjoint union: #(S + T) = #S + #T (2.18) This motivates the use of the notation ‘‘+’’ for disjoint union. We can extend disjoint union to any number of sets. In general, the notation S1 + S2 + . . . + Sn stands for the set in which each value is chosen from one of S1 , S2 , . . . , or Sn . The functional language HASKELL has algebraic types, which we can under- stand in terms of disjoint unions. In fact, the HASKELL notation is very close to our mathematical disjoint-union notation. EXAMPLE 2.12 HASKELL algebraic types Consider the HASKELL type definition: data Number = Exact Int | Inexact Float left u left v + = u v a b c right a right b right c S T Figure 2.4 Disjoint union of sets S + T (or left S + right T ) S and T.

- 48. 2.3 Composite types 29 The set of values of this algebraic type is: Number = Exact Integer + Inexact Float The values of the type are therefore: {. . . , Exact(−2), Exact(−1), Exact 0, Exact(+1), Exact(+2), . . .} ∪ {. . . , Inexact(−1.0), . . . , Inexact 0.0, . . . , Inexact(+1.0), . . .} The following code illustrates construction of an algebraic value: let pi = Inexact 3.1416 in . . . The following function illustrates tag test and projection: rounded num = -- Return the result of rounding the number num to the nearest integer. case num of Exact i -> i Inexact r -> round r This uses pattern matching. If the value of num is Inexact 3.1416, the pattern ‘‘Inexact r’’ matches it, r is bound to 3.1416, and the subexpression ‘‘round r’’ is evaluated, yielding 3. We can also understand the discriminated records of ADA in terms of disjoint unions. EXAMPLE 2.13 ADA discriminated records (1) Consider the following ADA definitions: type Accuracy is (exact, inexact); type Number (acc: Accuracy := exact) is record case acc of when exact => ival: Integer; when inexact => rval: Float; end case; end record; This discriminated record type has the following set of values: Number = exact Integer + inexact Float Note that the values of type Accuracy serve as tags. The following code illustrates construction of a discriminated record: pi: constant Number := (acc => inexact, rval => 3.1416);

- 49. 30 Chapter 2 Values and types The following function illustrates tag test and projection: function rounded (num: Number) return Float is -- Return the result of rounding the number num to the nearest integer. case num.acc is when exact => return num.ival; when inexact => return Integer(num.rval); end case; end; A discriminated record’s tag and variant components are selected in the same way as ordinary record components. When a variant such as rval is selected, a run-time check is needed to ensure that the tag is currently inexact. The safest way to select from a discriminated record is by using a case command, as illustrated in Example 2.13. In general, discriminated records may be more complicated. A given variant may have any number of components, not necessarily one. Moreover, there may be some components that are common to all variants. EXAMPLE 2.14 ADA discriminated records (2) Consider the following ADA definitions: type Form is (pointy, circular, rectangular); type Figure (f: Form) is record x, y: Float; case f is when pointy => null; when circular => r: Float; when rectangular => w, h: Float; end case; end record; This discriminated record type has the following set of values: Figure = pointy(Float × Float) + circular(Float × Float × Float) + rectangular(Float × Float × Float × Float) Here are a few of these values: pointy(1.0, 2.0) – represents the point (1, 2) circular(0.0, 0.0, 5.0) – represents a circle of radius 5 centered at (0, 0) rectangular(1.5, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0) – represents a 3×4 box centered at (1.5, 2)