The Science Behind Good Page Design

- 1. Contact me if you need design advice or if you have any design problems, want to share some design examples (I collect them), or you just want to chat! Email: tmkister@nanatoo.com

- 2. Audience analysis is widely accepted as a core component of the information-development lifecycle.

- 3. Audience analysis typically includes collecting information about your users – from demographic data (such as age, profession, geographic location) to underlying values.

- 4. However, we tend to overlook one of the most important factors in understanding our audience: That is, how human beings…

- 5. …regardless of age, economic status, education, or any other particulars, perceive and processes visual information on the most basic physiological and neurological levels.

- 6. A simplified way of understanding visual perception is to think of it in terms of two phases: Sensation and Translation.

- 7. Sensation occurs in the eye…

- 8. …and translation occurs in the brain.

- 9. During sensation, light enters the eye through the pupil and the lens.

- 10. The lens inverts the light…

- 11. …and focuses it on the retina, which is the area at the back of the eye that contains photoreceptor cells…

- 12. …called rods and cones.

- 13. Rods facilitate vision in low-light conditions and are associated with peripheral vision.

- 14. Cones facilitate vision in normal light conditions and are associated with the perception of color. There are three main types of cones cells, each of which responds to either red, green, or blue light.

- 15. Cone cells are also associated with detail and allow us to detect contrast between features, including shadows and edges. This, in turn, allows us to perceive both shape and position.

- 16. The way that our photoreceptors works means that there are essentially three types of visual information that we initially perceive: shape, color, and position.

- 17. Shape, color, and position are directly correlated with the basic design elements, or the elements of art, taught to design students. While there is some variation in how basic design elements are taught, from a physiological perspective, the traditionally taught elements all represent some form of shape, color, and position.

- 18. Texture, for example, is an effect created with a combination of shape, color, and position.

- 19. And these three basic design elements…

- 20. …are the building blocks of page design, and make up the overall layout, individual elements, and text.

- 21. It is important to note that, while we traditionally treat text as separate from visual design, and both are very complex to master, the way we process them is essentially the same.

- 22. Each of the three basic design elements has attributes – or characteristics – that we choose as page designers. For example, shape attributes can include curve, angle, and symmetry.

- 23. The attributes that we choose convey meaning to our users. For example, curves and circles tend to convey connection, community, and wholeness, while right angles and squares tend to convey stability, order, and logic.

- 24. The same is true for color…

- 26. …position…

- 28. …and typography.

- 29. So, how do we derive meaning from these basic elements and their attributes? That happens during the second basic phase of perception: translation...

- 30. …which occurs in the brain. The exact workings of the brain are still largely a mystery.

- 31. In general, our brain works in very complex ways to detect features…

- 32. …identify and categorize them…

- 33. …discard or ignore irrelevant features…

- 34. Placeholder

- 35. …create patterns to fill in any missing information…

- 36. …and make associations with what we already know about the world…

- 37. …based on our past experiences.

- 38. To complicate matters, these processes occur in sequence, in unison, and in reverse.

- 39. There are several frameworks for understanding how we derive meaning from visual stimuli. One such early framework, known as Gestalt, was born from the study of philosophy…

- 40. …and emerged around the same time that photography and motion pictures became popular.

- 41. Gestalt theorists realized that what we perceive does not logically follow from what is perceivable. For example, they noted how a series of static images that shift position creates an illusion of motion, and called this the “phi phenomenon.”

- 42. They noted that “the whole is something other than the sum of its parts” so that, two plus two equals…

- 43. …a cat!

- 44. In this picture for example, we perceive a dog…

- 45. …despite the fact that each individual element has no resemblance to the actual parts of a dog.

- 46. There are many Gestalt principles that range from simple to complex, and they often interact with one another. Proximity, for example…

- 47. …is a simple principle of grouping that describes how we tend to categorize elements that are positioned close to another…

- 48. …as related.

- 49. And the grouping principle of proximity…

- 50. …can interact with other grouping principles, such as symmetry.

- 51. A more complex Gestalt principle is Reification, in which our minds perceive visual stimuli that doesn’t actually exist in order to make sense of what we see. In this example…

- 52. …our minds perceive a triangle that doesn’t actually exist…

- 53. …because we can make sense of a triangle much more easily than we can make sense of the three other shapes.

- 54. Multistability describes how – when visual stimuli are ambiguous – we can move between interpretations that are entirely different.

- 55. And we do the same thing with text.

- 56. All of these principles, or heuristics, describe how we process visual information, and they form the basis for the traditionally taught design principles. Just as with the design elements, there are many variations on how design principles are taught, and they usually represent a combination of various related concepts.

- 57. For example, emphasis and contrast are listed as two separate principles, but are actually related concepts because you often convey emphasis…

- 59. Therefore, just as with the three elements of design, the principles of design can be simplified and distilled into contrast, repetition, alignment, and position...

- 60. …or CRAP (which is a common mnemonic used in page design).

- 61. However, even conceiving of these as four separate concepts is actually a bit problematic.

- 62. Alignment is a type of position…

- 63. …and the terms “contrast” and “repetition”…

- 64. …and the terms contrast and repetition relate to the same thing: the degree of difference on a spectrum that ranges from completely unrelated to exactly the same.

- 65. That’s why – on the most basic level – all design principles can be thought of in terms of a single concept: Gradient.

- 66. The concept of a gradient can be applied to each of the basic design elements, including shape…

- 67. …color…

- 68. …and position.

- 69. You can see the concept of gradient in page design all the time, with headings (which have graduated sizes, weights, and surrounding white space)…

- 70. …with lists (which use increasing indents for subordinate items)….

- 71. …and with color.

- 72. There is another important concept related to the science of good page design: attention, or the degree to which a person successfully attends to, or focuses on, something.

- 73. Our attention is instinctively and almost instantaneously attracted to certain things. For example, if I show you this slide, your eyes inevitably return to the white circle. We are evolutionarily “hard wired” to pay attention to certain things…

- 74. …things that include physical features, like edges…

- 75. …and conceptual things, like faces…

- 76. …food…

- 77. …danger…

- 78. …and sex…

- 79. …and one of the things we are most sensitive to is difference.

- 80. The initial stages of our attention to these things occurs involuntarily, and is a function of how our eyes and minds work. When light enters the eye, it is focused on a small area of the retina called the fovea.

- 81. The fovea contains a much greater density of cone cells than the rest of the retina, and is the only area of the retina that allows us to perceive a high level of detail. Because this is such a small area (about one percent of the retina)…

- 82. …most of our field of view is blurry…

- 83. …and only a small area is actually in focus...

- 84. …an area about the size of your thumbnail if you hold your thumb up at arm’s length.

- 85. Because this area is so small, our eyes constantly move across our field of view in involuntary, abrupt movements called “saccades.”

- 86. Our minds then stitch the small, in-focus images together into a perceived whole.

- 87. In page design, we can make design choices that direct the user’s attention in ways that are automatic and do not require any conscious effort.

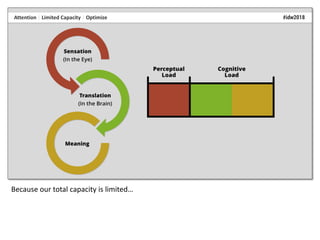

- 88. Another key factor in attention is the fact that our capacity to process information is limited. One way to think of this is in terms of perceptual and cognitive load.

- 89. Perceptual load refers to the amount of stress placed on our ability to process visual stimuli given a perceptual task.

- 90. In this case, the task is to identify either the N or the X.

- 91. Cognitive load refers to the amount of stress placed on our ability to translate and interpret meaning in order to achieve full comprehension.

- 92. Because our total capacity is limited…

- 93. …our job as page designers is to optimize perceptual load in order to maximize the resources available for attention and comprehension.

- 94. The design of this webpage has a high perceptual load because of all the visual stimuli that isn’t related to accomplishing a task.

- 95. This webpage design has an even higher perceptual load. At first glance, it seems to conform to the principles of good design. However, on closer inspection you can see that it lacks the necessary visual cues needed to accomplish even the most basic online task – there are none of the traditional menus, buttons, etc.

- 96. Generally speaking, high-load designs decrease information-processing speed and accuracy. Therefore, you might think that our job is to minimize perceptual load, but that’s an oversimplification. You can minimize perceptual load...

- 97. ...by creating page designs that are static and boring. However, simply minimizing perceptual load overlooks other important factors.

- 98. It’s important to note that we instinctively and automatically assign meaning to everything, and then discard or ignore what is irrelevant…

- 99. So, if a design includes characteristics that are incongruent with meaning, we have to sort through what matters and what doesn’t and use our conscious mind to comprehend meaning, so that speed and accuracy are low.

- 100. If a design includes characteristics that are neutral in terms of meaning, speed and accuracy increase.

- 101. By making visual stimuli more complex in ways that are congruent with meaning, speed and accuracy increase even more.

- 102. There is another important component of attention that is often overlooked, particularly in certain genres of information development like technical communication. If perceptual load relates to perceivability, and cognitive load relates to understandability...

- 103. ...then both work together to capture and direct our attention...

- 104. …which facilitates comprehension and, therefore, usability. If you think of both as existing along a normal curve…

- 105. …too little load doesn’t hold our attention and doesn’t facilitate comprehension…

- 106. …too much load overwhelms our capacity for attention and doesn’t facilitate comprehension…

- 107. …and so the key is to find the sweet spot in the middle – the point at which page design facilitates comprehension. Which brings us to the second important component of page design that is so often overlooked...

- 108. ...pleasure!

- 109. When perceptual and cognitive load are successfully optimized, we experience pleasure.

- 110. There are at least two types of pleasure that are important in page design. One occurs at the “a-ha” moment of comprehension...

- 111. …such as when we are shown an apparently meaningless image…

- 112. …and then are shown a caption that shows that the image means something. Research has shown that, at the moment of comprehension, our brains release endomorphins, which suppress pain and are associated with pleasure.

- 113. The second type of pleasure is aesthetic pleasure. Statistic analyses have shown that aesthetic pleasure occurs when there is a balance between typicality and novelty…

- 114. …between unity and variety…

- 115. …between sameness and difference. Which brings us back again to the primary principle of page design: gradient.

- 116. The pleasure that we experience when engaging with well-design information has a Pavlovian positive-reinforcement effect, in which our information-seeking behavior is rewarded, which encourages and facilitates further engagement.

- 117. So, the way we process visual information is directly correlated with best practices in page design…

- 118. …but how do you combine the basic design elements…

- 119. …with the fundamental design principle of gradient into successful page designs?

- 120. Of course, it’s a complex answer – there are no rote recipes for good design…

- 121. …in part, because there are so many variables. As soon as you make one design choice…

- 122. …it’s going to impact other design choices because page design is essentially about relationships…

- 123. …the relationships between the elements on a page.

- 124. Design requires a type of logic called conditional reasoning, which consists of “if-then” choices. Here, for example, if I use two narrow columns, then I should use more white space between the paragraphs instead of using a first-line indent. Otherwise, the indentation for both paragraphs and lists can cause the eye to get lost while tracking across lines of text.

- 125. The design process is very similar to the writing process – we combine basic elements based on common principles to create meaning.

- 126. Just as with writing, there are a number of sources that provide rules and guidelines, and it takes time and experimentation to really figure out how to apply them in real life – to figure out what “proper” alignment and a “logical” color palette are.

- 127. And – just as with writing – there is also a lot of bad advice out there – which is why having a deeper understanding is so important.

- 128. A good way to learn is to look in areas of information development you might not normally be exposed to – areas like user experience design, presentation design, and data visualization.

- 129. Since we’re just about out of time, I’d like to share just two guiding principles with you – principles that can be used for every design choice. The first is Just-Noticeable Difference (JND), which is a technical term used in perception studies…

- 130. …that refers the degree of difference required to be detected 50% of the time.

- 131. Because we assign meaning to everything and then discard or ignore what is irrelevant – if you use just enough difference to be noticeable, then that conserves cognitive resources and lowers perceptual and cognitive load.

- 132. Which is one reason this is bad advice…

- 133. …using arbitrary font weights creates an additional degree of difference that is unnecessary and increases load. The change in font weights has no purpose, other than to introduce difference simply for the sake of difference.

- 134. Which brings us to the second piece of advice, which is to use intentional design. Careless design choices cause extra perceptual and cognitive load by either contradicting meaning…

- 135. Placeholder

- 136. …or by adding visual clutter. (Don’t use decoration.)

- 137. Instead, make sure every design choice is intentional and has a purpose.

- 138. And, when in doubt, keep it simple.

- 139. We have taken just a peek at how the science of human visual perception forms the basis for good page design, and there’s so much more to explore. I just want to leave you with one final thought. Despite a long tradition of silos in both education and business…

- 140. …that positions content and design as separate things that are in opposition to one another…

- 141. …content and design are inseparable, and both are necessary in creating high-quality information deliverables.

- 142. Design without content is meaningless, and content without design is incomprehensible. And, even with all of the design elements removed, this block of text is still in a font, in a color, in shape, positioned on the page. Without any design elements…

- 143. …you have nothing.

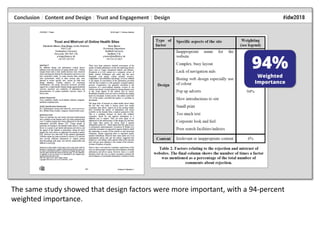

- 144. And a ton of research shows that design matters. A 2004 study of the effects of content and design on users of health-care websites showed that content factors had an 83-percent weighted importance in terms of trust and engagement.

- 145. The same study showed that design factors were more important, with a 94-percent weighted importance.

- 146. And design is particularly important during the initial stages of engagement…

- 147. …because effective visual design is so powerful that it can instill persistent trust and facilitate engagement, despite known issues with usability and content.

- 148. So, in terms of knowing your audience, know that good page design can make the difference between...

- 149. ...this...

- 150. ...and this.

- 151. Contact me if you need design advice or if you have any design problems, want to share some design examples (I collect them), or you just want to chat! Email: tmkister@nanatoo.com

- 152. To cite this presentation: Kister, Tina M. “The Science of Good Page Design (A Brief Introduction).” presented at Information Development World 2018: Building a Modern Online Technical Resource Center, Menlo Park, California, November 28, 2018. • Biederman, Irving, and Edward A. Vessel. “Perceptual Pleasure and the Brain: A Novel Theory Explains Why the Brain Craves Information and Seeks It Through the Senses.” American Scientist 94 (2006): 247–53. • Blijlevens, J, Clementine Thurgood, Paul Hekkert, Lin-Lin Chen, Helmut Leder, and T W. Allan Whitfield. “The Aesthetic Pleasure in Design Scale: The Development of a Scale to Measure Aesthetic Pleasure for Designed Artifacts.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 11 (February 1, 2017): 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000098. • Cairo, Alberto. “The Truthful Art: Data, Charts, and Maps for Communication.” Accessed November 9, 2018. https://www.amazon.com/Truthful-Art-Data-Charts- Communication/dp/0321934075/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1541766732&sr=8-1&keywords=the+truthful+art. • Chen, Kang-chen, and Hye Jung Choi. “Visual Attention and Eye Movements,” 2008. • Chugh, Sagar. “Aesthetics vs. Usability.” 00:01:40 UTC. https://www.slideshare.net/schugh/aesthetics-vs-usability. • Curtin, John J., and Bradley A. Fairchild. “Alcohol and Cognitive Control: Implications for Regulation of Behavior during Response Conflict.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 112, no. 3 (August 2003): 424–36. • Debue, Nicolas, and Cécile van de Leemput. “What Does Germane Load Mean? An Empirical Contribution to the Cognitive Load Theory.” Frontiers in Psychology 5 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01099. • Detlef, Pete. “Conducting an Audience Analysis: What Is Important to Your Audience.” 24 Hour Translation Services, 2017. https://www.24hourtranslation.com/conducting-an-audience-analysis-what-is-important-to-your-audience.html. • Duarte, Nancy. Slide:Ology: The Art and Science of Creating Great Presentations. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, 2008. • Goldstein, E. Bruce, and James Brockmole. Sensation and Perception. 10th ed. Cengage Learning, 2016. https://books.google.com/books?id=x5d4CgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Sensation+and+Perception&hl=en&sa=X& ved=0ahUKEwjxhM6rpNbdAhUN61MKHS2XClwQ6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q&f=false. • Grais, Stuart. “Gestalt Principles.” DePaul University, College of Computing and Digital Media. Accessed November 9, 2018. http://facweb.cs.depaul.edu/sgrais/gestalt_principles.htm. • Hart, Geoff. “Technical Communications Primer: Gestalt Theory and Visual Design.” TechWhirl, March 12, 2012. https://techwhirl.com/technical-communications-primer-gestalt-theory-and-visual-design/. Bibliography Page 1

- 153. • Johnson, Jeff. Designing with the Mind in Mind: Simple Guide to Understanding User Interface Design Guidelines. 2nd ed. Waltham, MA: Elsevier, 2014. • Kitenga, Te. “A World of Edges.” Accessed October 23, 2018. http://www.tekitenga.com/visual-perception/a-world-of- edges/. • Lavie, Nilli, Zhicheng Lin, Nahid Zokaei, and Volker Thoma. “The Role of Perceptual Load in Object Recognition.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 35 (2009): 1346–58. • Lindgaard, Gitte, Gary Fernandes, Cathy Dudek, and Judith Brown. “Attention Web Designers: You Have 50 Milliseconds to Make a Good First Impression!” Behaviour & Information Technology 25 (2006): 115–26. • Marciano, Hadas, and Yaffa Yeshurun. “Large Inter-Individual and Intra-Individual Variability in the Effect of Perceptual Load.” PLOS ONE 12, no. 4 (April 13, 2017): e0175060. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175060. • Mazza, Riccardo. Introduction to Information Visualization. London: Springer-Verlag, 2009. //www.springer.com/us/book/9781848002180. • Murphy, G., and C. M. Greene. “Perceptual Load Affects Eyewitness Accuracy and Susceptibility to Leading Questions.” Frontiers in Psychology 7 (2016). • Murphy, Gillian, John A. Groeger, and Ciara M. Greene. “Twenty Years of Load Theory—Where Are We Now, and Where Should We Go Next?” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 23, no. 5 (October 1, 2016): 1316–40. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0982-5. • Panday, V., Wouter M. Bergmann Tiest, and A. M. L. Kappers. “The Influence of Edges as Salient Features in Haptic Shape Perception of 3D Objects.” In 2011 IEEE World Haptics Conference, 529–32. Istanbul: IEEE, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1109/WHC.2011.5945541. • Pelli, Denis G. “Two Stages of Perception.” Theories of Vision, 1997. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/46fe/a20b34fc32f129cd9d7b3fa55fa221e1d8fd.pdf. • Peromaa, Tarja-L., and Pentti I. Laurinen. “Separation of Edge Detection and Brightness Perception.” Vision Research 44, no. 16 (July 1, 2004): 1919–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2004.03.005. • Purves, Dale, George J. Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, Lawrence C. Katz, Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, James O. McNamara, and S. Mark Williams. “Anatomical Distribution of Rods and Cones.” Neuroscience. 2nd Edition, 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10848/. Bibliography Page 2

- 154. • Purves, Dale, Brian B. Monson, Janani Sundararajan, and William T. Wojtach. “How Biological Vision Succeeds in the Physical World.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (2014): 4750–55. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1311309111. • Roelofs, A., M. van Turennout, and M. G. H. Coles. “Anterior Cingulate Cortex Activity Can Be Independent of Response Conflict in Stroop-Like Tasks.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, no. 37 (September 12, 2006): 13884– 89. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0606265103. • Shaikh, A. Dawn, Barbara S. Chaparro, and Doug Fox. “Perception of Fonts: Perceived Personality Traits and Uses.” Usability News 8 (2006): 1–6. • Sillence, Elizabeth, Pam Briggs, Lesley Fishwick, and Peter Harris. “Trust and Mistrust of Online Health Sites.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 663–70. ACM, 2004. • Stribley, Mary. “20 Design Rules You Should Never Break.” Learn, April 14, 2015. https://www.canva.com/learn/design- rules/. • Tractinsky, Noam, Adi S. Katz, and Dror Ikar. “What Is Beautiful Is Usable.” Interacting with Computers 13 (2000): 127–45. • Treisman, Anne, and Stephen Gormican. “Feature Analysis in Early Vision: Evidence from Search Asymmetries.” Psychological Review 95 (1988): 15–48. • Tufte, Edward R. Envisioning Information. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Pr, 1990. • Ware, Colin. Visual Thinking for Design. Amsterdam: Elsevier Morgan Kaufmann, 2011. • Williams, Robin. The Non-Designer’s Design Book: Design and Typographic Principles for the Visual Novice, 2015. • Wolfe, Jeremy M. “Guidance of Visual Search by Preattentive Information.” In Neurobiology of Attention, 101–4. Elsevier, 2005. • Wolfe, Jeremy M., Kyle R. Cave, and Susan L. Franzel. “Guided Search: An Alternative to the Feature Integration Model for Visual Search.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 15 (1989): 419–33. • Wolfe, Jeremy M., and W. Gray. “Guided Search 4.0.” Integrated Models of Cognitive Systems, 2007, 99–119. • Yau, Nathan. Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics. John Wiley & Sons, 2011. Bibliography Page 3

- 155. Sensation refers to the process of receiving visual stimuli from the outside world. Translation refers to the neurological and chemical processes that occur after light is converted into electrochemical impulses and sent through the optic nerve to the brain. The Science of Good Page Design (A Brief Introduction) Introduction Information developers should be proficient in page design, as well as writing, as both are essential in creating deliv- erables that are easy to find, read, use, understand, and remember. While audience analysis is a fairly standard component of best practices in information development, we tend to overlook one of the most important characteristics of our audience – that is, how human beings, regardless of age, economic status, gender, and other demographic particulars, process visual information. Tina M. Kister Consultant, Nanatoo Communications Sensation During sensation, light enters the eye through the cornea, the pupil, and the lens. The lens inverts the light and focuses it on the retina, which is the area at the back of the eye that contains photoreceptor cells called rods and cones. Visual Perception Design is an integral component of all information develop- ment, and the physiology and anatomy of human perception form the basis of best practices in design. With a deep under- standing of how people process information, you can make design decisions that reinforce meaning, improve processes, and result in high-quality deliverables. A simplified way of understanding visual perception is to think of it in terms of two phases: sensation and translation. Sensation occurs in the eye, and translation occurs in the brain. Rods and Cones Rods facilitate vision in low-light conditions and are associated with peripheral vision. Cones facilitate vision in normal light conditions and are associated with the percep- tion of color. There are three main types of cones cells, each of which responds to either red, green, or blue light. Cone cells are also associated with perception of detail and allow us to detect contrast between features, including shadows and edges. This, in turn, allows us to perceive both shape and position.

- 156. Cone cells are associated with perception of detail and allow us to detect contrast between features, including shadows and edges. Cone cells also allow us to perceive color, and different cone cells are sensitive to either red, green, or blue light. There are essentially three types of visual information that we initially perceive: shape, color, and position. w is a Gestalt heuristic that describes how, when visual stimuli are ambiguous, we can move between interpretations that are entirely different. Design Elements (Shape, Color, Position) The way that our photoreceptors works means that there are essentially three types of visual informa- tion that we initially perceive: shape, color, and position. These three elements are directly correlated with the basic design elements taught to all beginning designers. Because the three basic elements can be combined in various ways to form the tradition- ally taught elements, there is some variation in how basic design elements are taught. However, it’s helpful to remember that, from a physiological perspective, the traditionally taught elements all represent some form of shape, color, and position. Each of the three basic design elements (of shape, color, and position) has attributes – or characteristics – that we choose as page designers, and these attributes convey meaning. Translation Translation occurs in the brain, and, while sensation relates primarily to receiving visual stimuli, translation relates to how we derive meaning from visual stimuli. In general, our brain works in very complex ways to detect features in our field of vision, and then to identify, categorize, and organize the features; discard or ignore irrelevant features; create patterns to fill in missing information; and make associations with what we already know about the world based on our past experiences. Gestalt Heuristics There are several frameworks for understanding how we derive meaning from visual stimuli. One such frame- work, known as Gestalt, describes how we interpret visual stimuli. There are many Gestalt princi- ples that range from simple to complex, and they often interact with one another. Design Principles (or Gradient) Frameworks that describe how we derive meaning from visual stimuli are the basis for the tradition- ally taught design principles, which represent a combination of related concepts. In page design, the basic design principles are often simplified to Contrast, Repetition, Alignment, and Position, or CRAP. However, they can be further distilled into the single concept of gradient, or degree of difference.

- 157. Traditional design principles can be distilled into the single concept of gradient, or the degree of difference in the attributes chosen for the basic design elements. The concept of gradient is evident in all page design, including in the use of headings (with graduated weights and sizes), lists (with increasing indentation for subordinate list items), and color, as demonstrated in the web-page design for Information Development World 2018. Our eyes and minds are predisposed to direct our attention to certain things, which include features like edges, and also include concepts like faces, food, danger, and sex. One of the things we are most sensitive to is difference. Attention There is another important concept related to the science of good page design: attention, or the degree to which a person successfully “attends to,” or focuses on, something. Instinctive and Automatic Our attention is instinctively attracted to certain features (such as edges) as well as conceptual things (like faces, food, danger, and sex, and difference). Our eyes and minds are “hard-wired” (evolutionarily predisposed) to direct our attention to differ- ence, and this is reinforced by how our eyes move across our field of view in short, abrupt movements called saccades. Saccades are necessary because only a small area within our field of view is actually in focus – most of our field of view is blurry. Saccades allow us to receive several small, in-focus images, which our minds then stitch together into a perceived whole. As page designers, we can make design choices that direct user attention before conscious effort is engaged.

- 158. The way we process visual information is directly related to the basic design elements and principles used in page design, and the application of best practices directs the user’s attention to deliverables that are easy to find, read, understand, use, and remember. Limited Capacity Another key factor in attention is the fact that our capacity to process infor- mation is limited. One way to think of our attention capacity is in terms of perceptual and cognitive load. Percep- tual load refers to the amount of stress placed on our ability to process visual stimuli given a perceptual task. Cogni- tive load refers to the amount of stress placed on our ability to translate and interpret meaning in order to achieve full comprehension. Our job as page designers is to optimize perceptual load in order to maximize the resources available for attention and comprehen- sion. Pleasure Another important component of attention is pleasure. Studies have shown that the moment of compre- hension is associated with a release of endomorphins, which are associated with pleasure. Studies have also shown that aesthetic pleasure is related to finding a balance between sameness and difference, which, in turn, brings us back to the distilled design principle of gradient. The pleasure that we experi- ence when interacting with high-quality information reinforces and encourages information-seeking behavior and leads to further audience engagement. Application There are no rote recipes for good design, in part because there are so many vari- ables. Good page design is about the relationships between page elements, and good design choices are based on using conditional reasoning, or “if-then” logic. Just as with writing, there are a number of sources that provide rules and guide- lines, and it takes time and experimentation to figure out which ones are valid and how to apply them. A good way to learn is to look in areas of information develop- ment you might not normally be exposed to – areas like user experience design, presentation design, and visualizing information (statistics). Just-Noticeable Difference and Intentional Design The key to successful page design is to use the three design elements (shape, color, and position), and alter their attributes (e.g., angle, hue, and alignment) along a gradient of difference using Just-Noticeable Difference (just enough difference to convey meaning) and intentional design (making design choices with a purpose). Using these two concepts will help you make design choices that optimize percep- tual and cognitive load, direct the user’s attention, and facilitate comprehension, usability, and engagement. Conclusion Despite a long tradition of silos in both education and business that positions content and design as separate things that are in opposition to one another, content and design are inseparable, and both are necessary in creating high- quality information deliverables. Research has shown that design factors are more important than content factors, particularly during the initial stages of engage- ment. Effective visual design is so powerful that it can instill persistent trust and facilitate engagement, despite known issues with usability and content. Recommended Reading Johnson, Jeff. Designing with the Mind in Mind: Simple Guide to Understanding User Interface Design Guidelines. 2nd ed. Waltham, MA: Elsevier, 2014. Duarte, Nancy. Slide:ology: The Art and Science of Creating Great Presentations. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, 2008. Goldstein, E. Bruce, and James Brockmole. Sensation and Perception. 10th ed. Cengage Learning, 2016. Williams, Robin. The Non-Designer’s Design Book: Design and Typographic Princi- ples for the Visual Novice, 2015. Contact Tina M. Kister Nanatoo Communications tmkister@nanatoo.com (435)-260-1565 www.nanatoo.com